The Temple Israel Museum has collected liquor jugs by Leadville Jewish merchants since the beginning of collecting artifacts for the museum. The museum has amassed a good collection of over 30 jugs, most in the sizes of half gallon and one gallon. Identification of who sold the jugs of liquor is easy since they have printed on them a name or business name with a city, state, and address. However, identifying dates and the jug manufacturers have been a big unanswered question only being able to assign the general dates of when the business was known to exist, which in some cases was for over 30 years. To narrow down the dates and determine manufacturers, more information was needed. This writing summarizes the research process and presents the findings with details in the appendices.

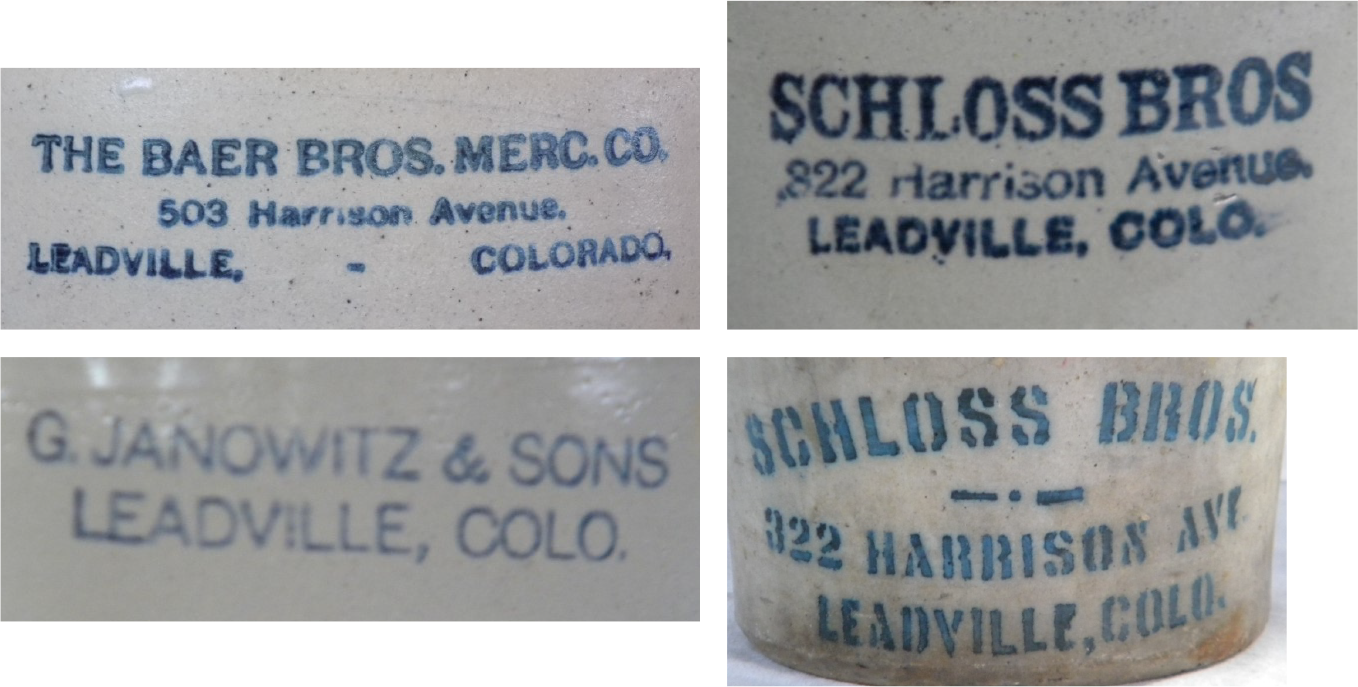

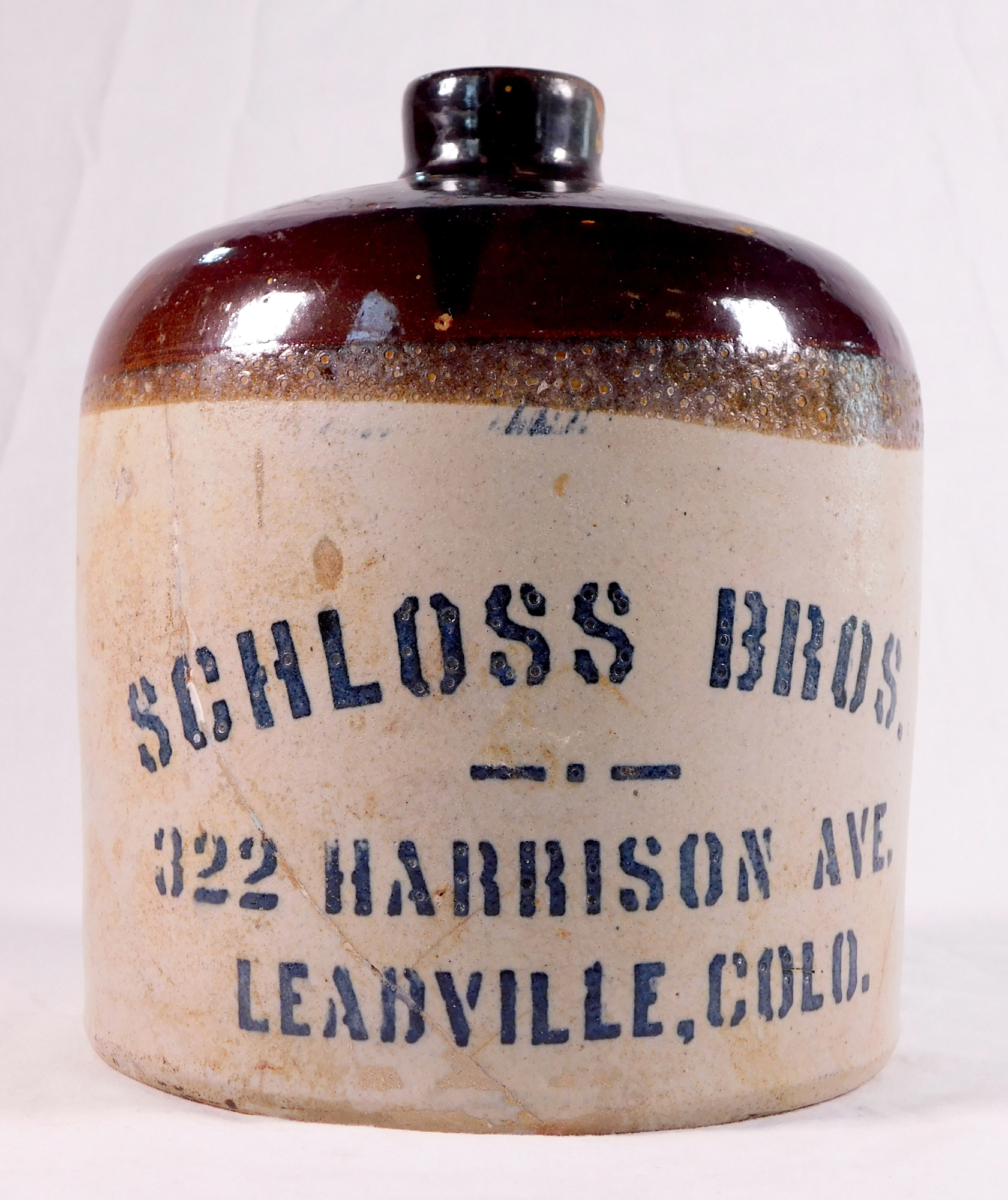

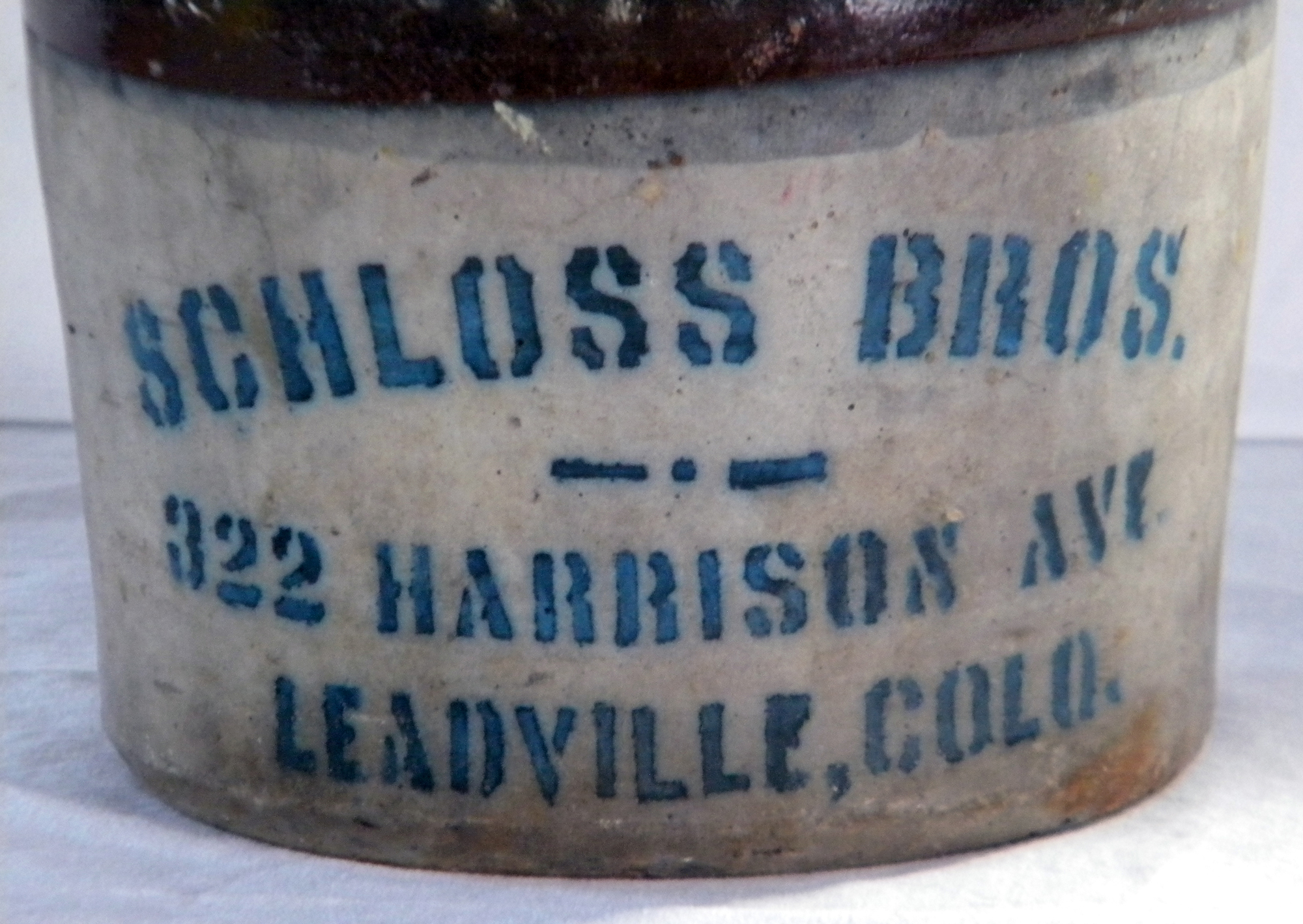

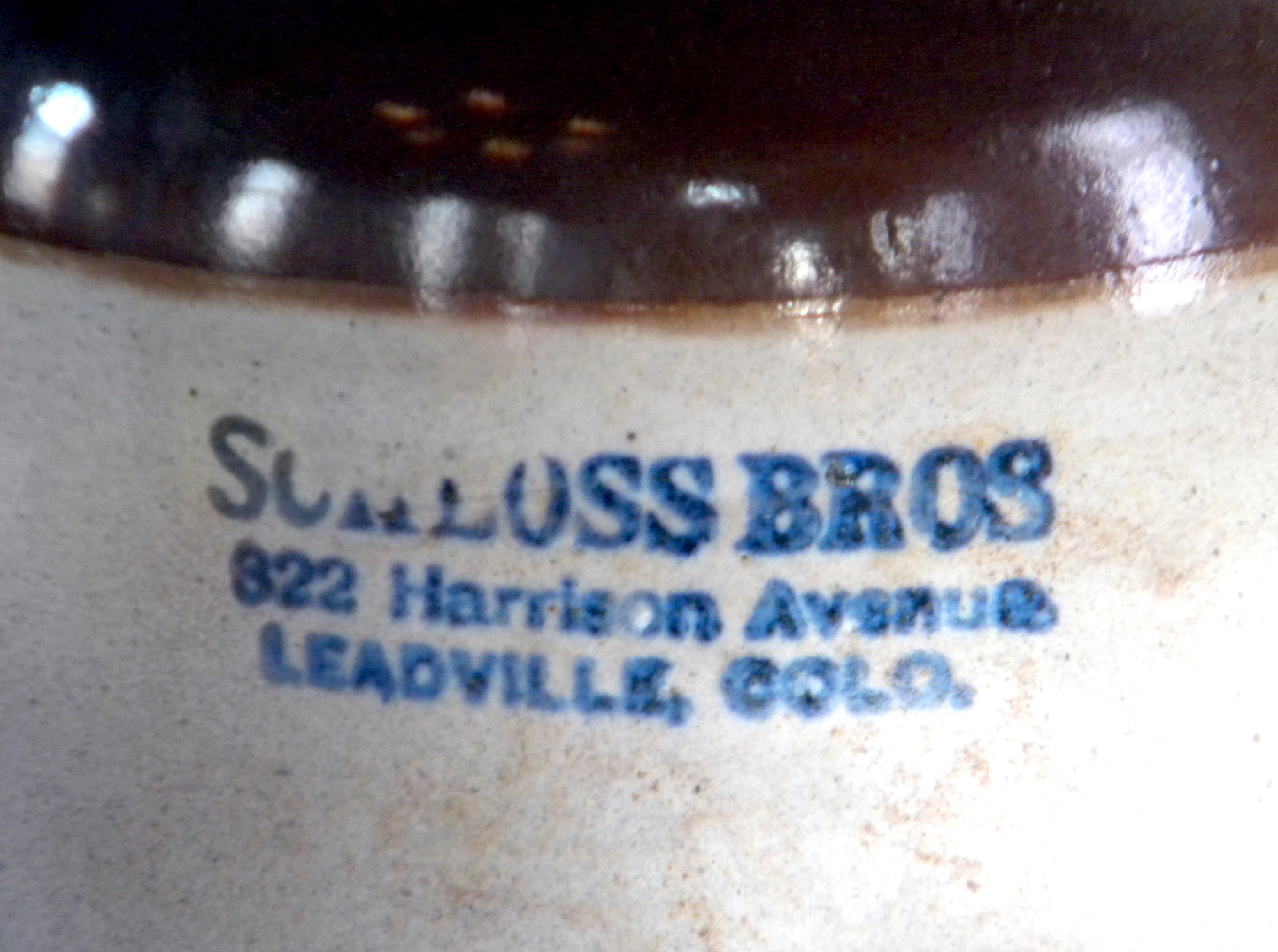

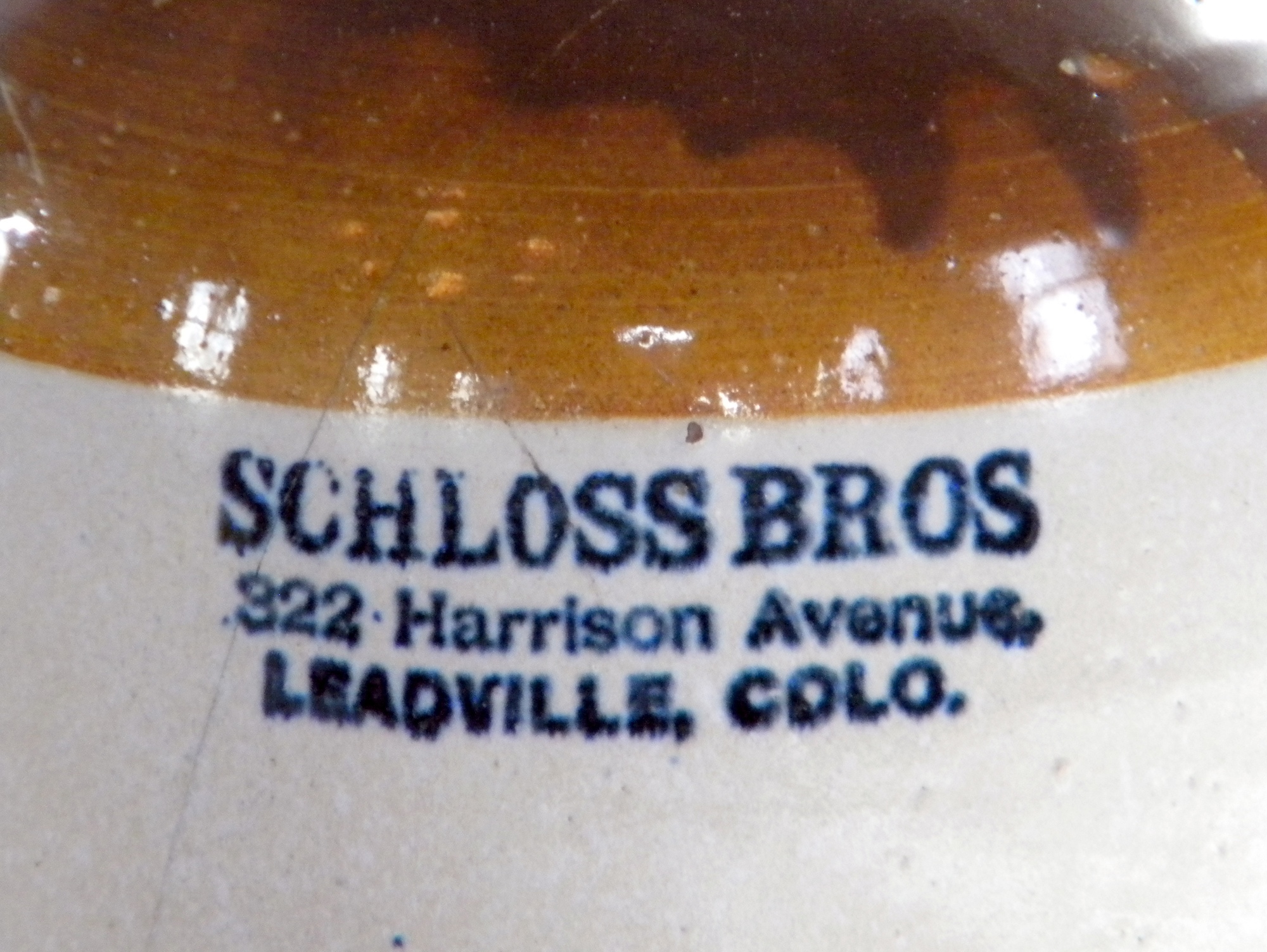

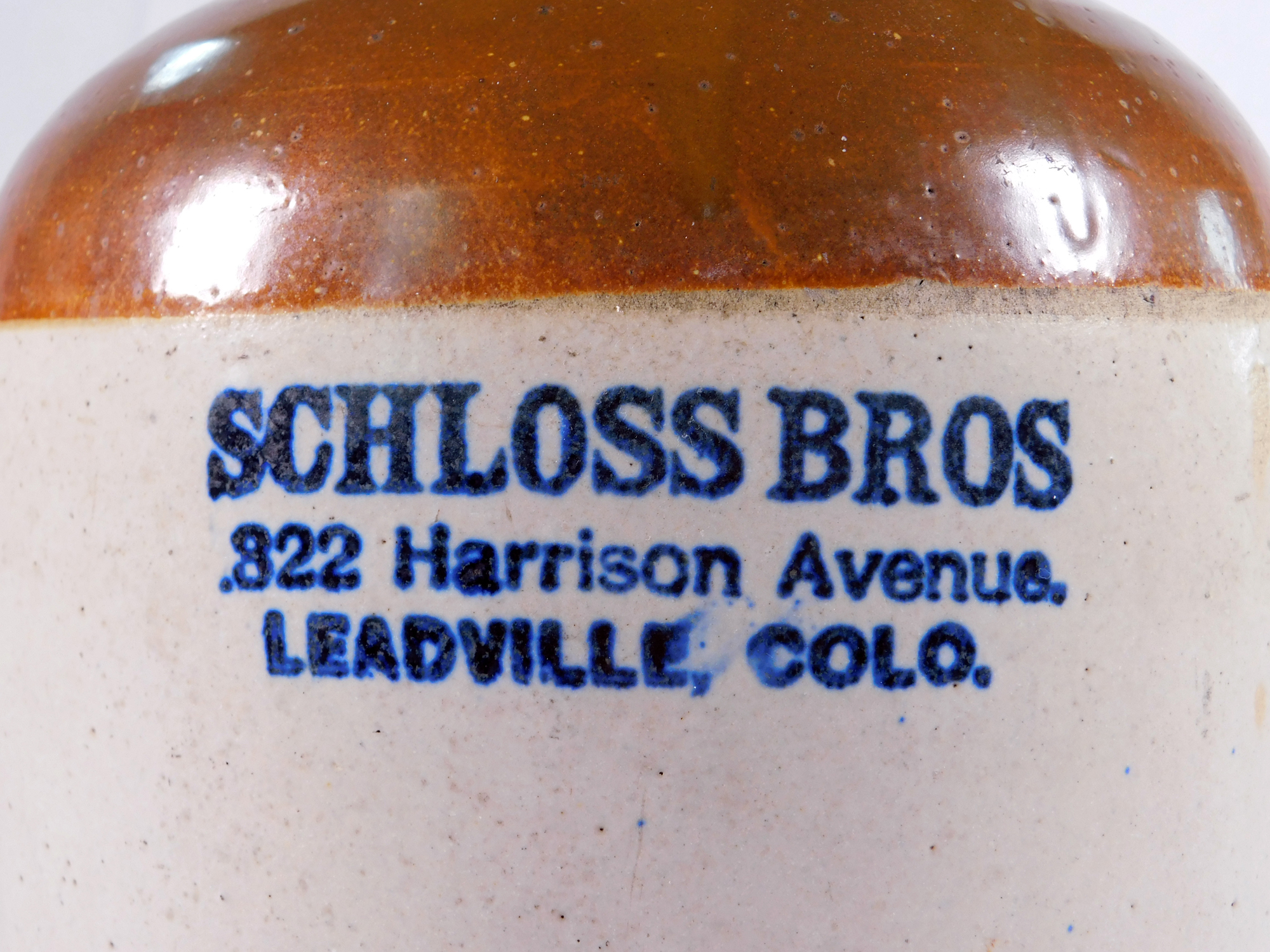

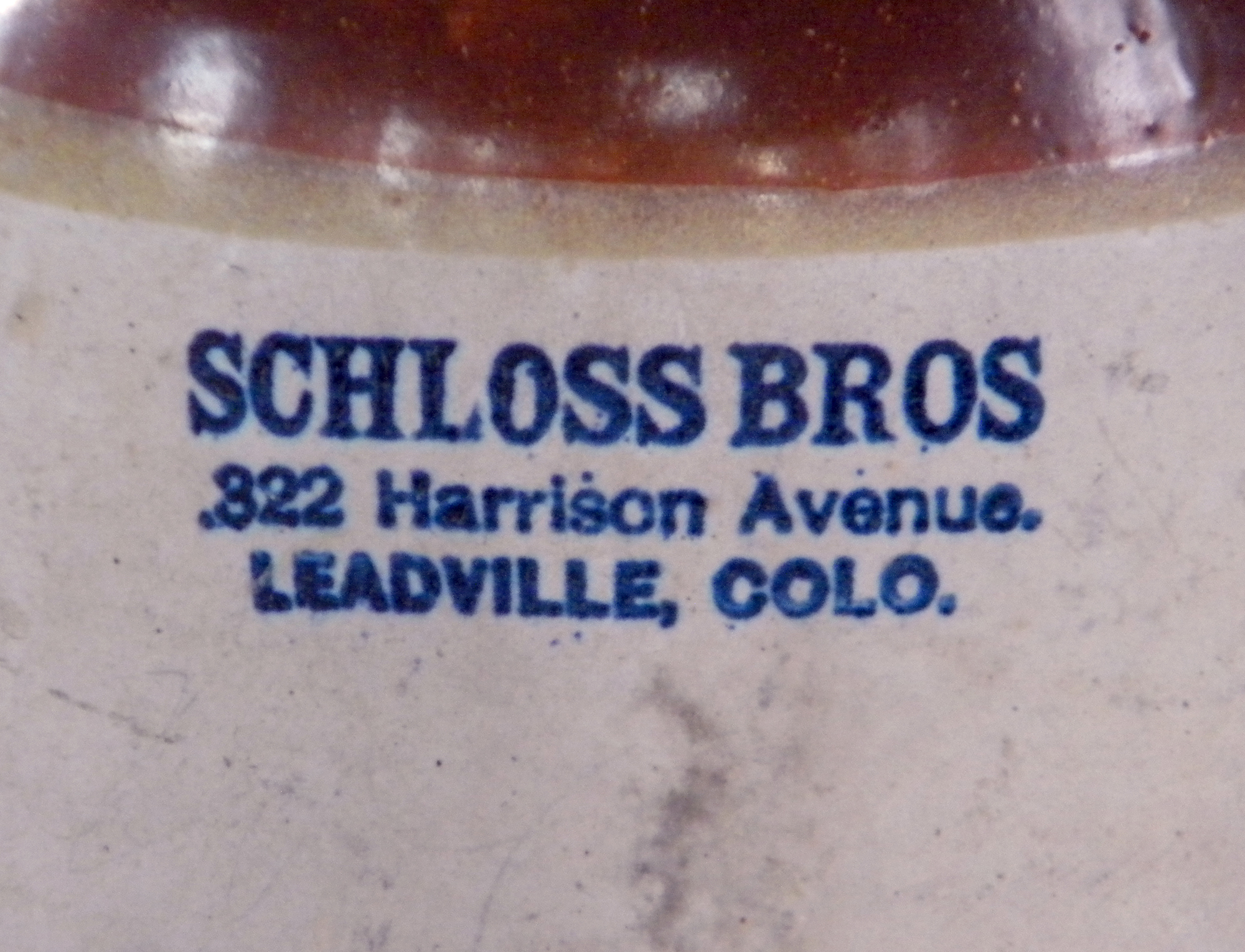

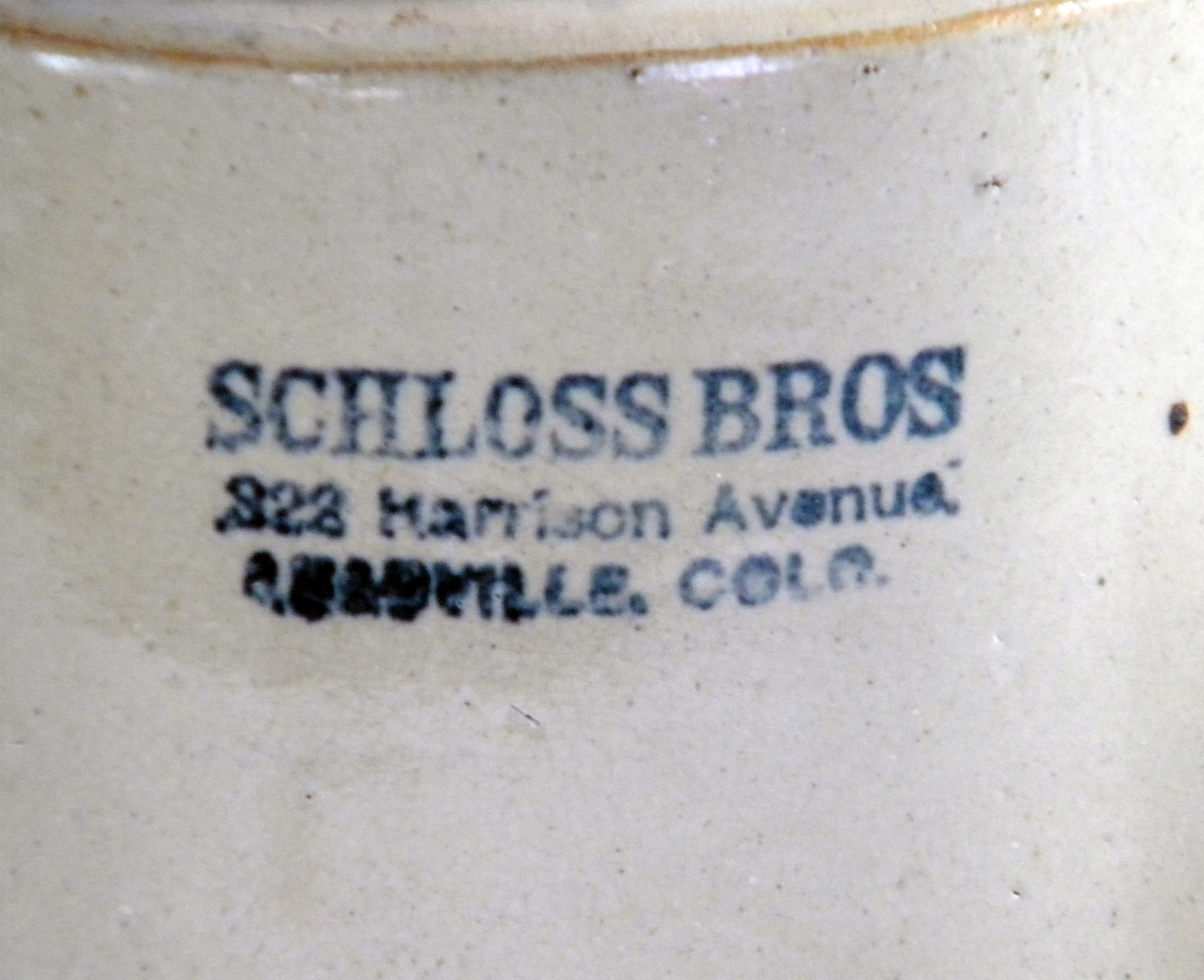

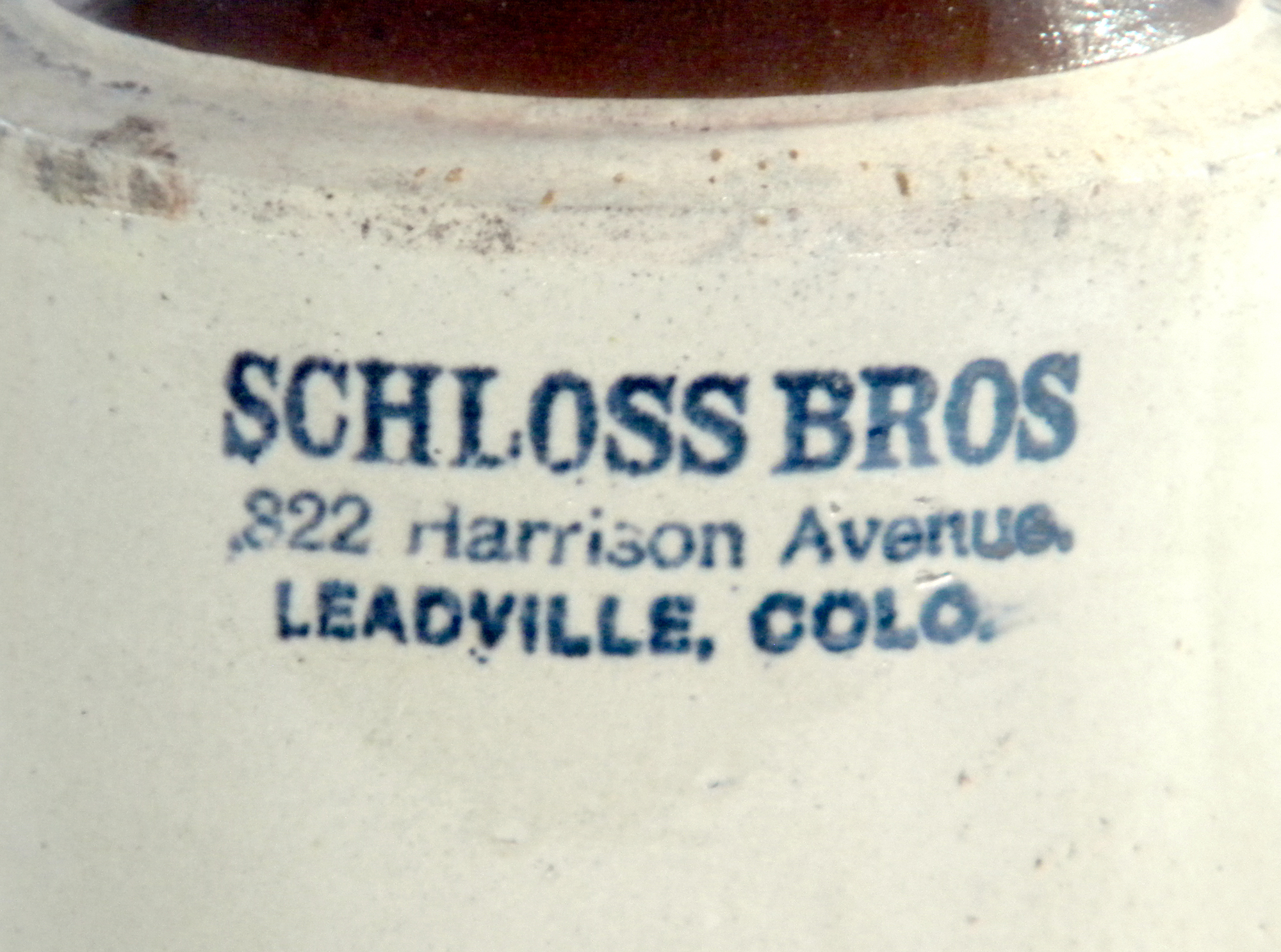

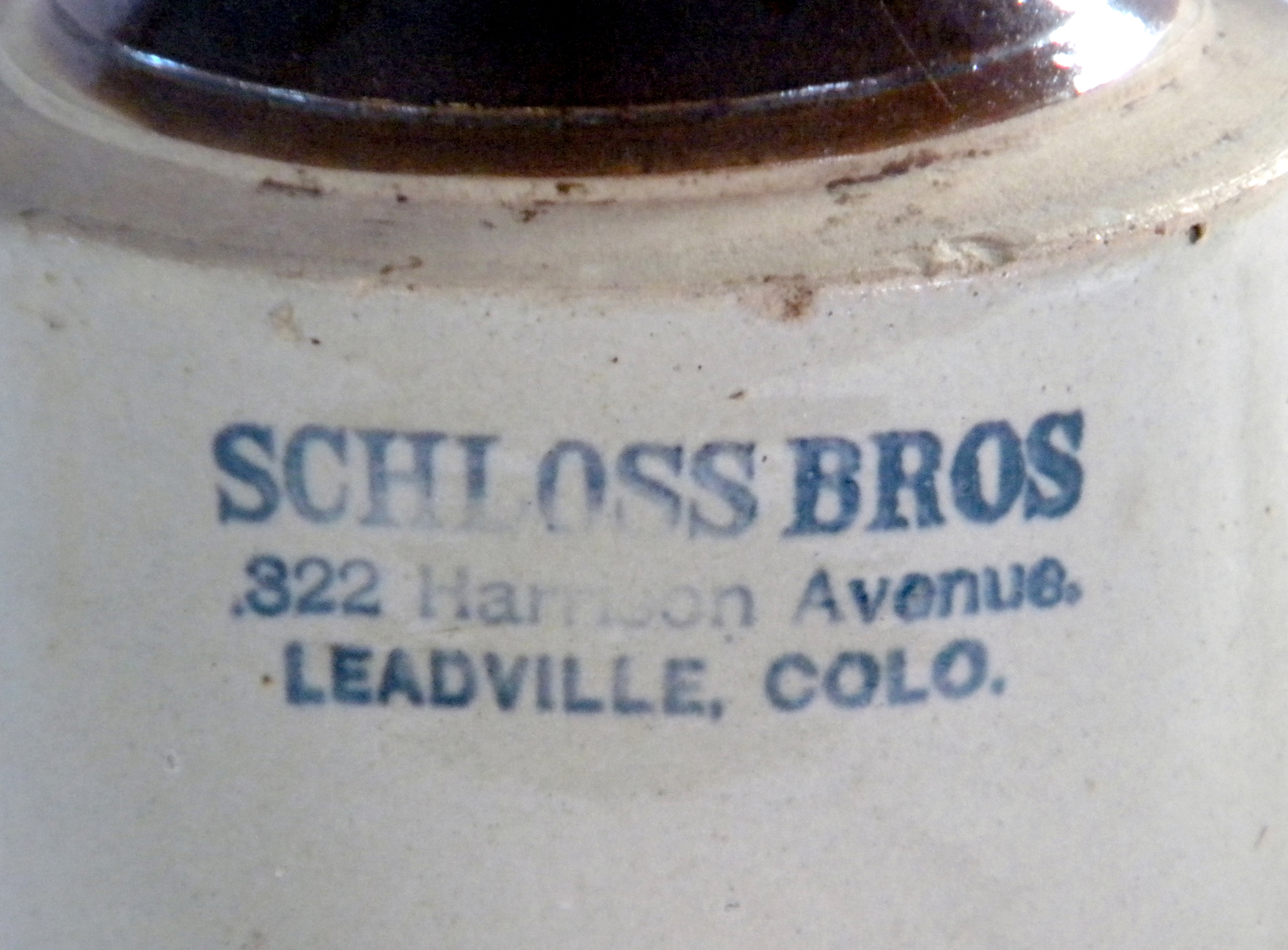

Liquor jugs by Schloss Brothers and others.

The first step in the process was to create a spreadsheet of all the jugs in the collection with its descriptive and measurable data along with collecting photographic images of the jugs. Upon inspecting the jugs, either in person or by photos, the different groupings of similar jugs became quite clear as to which manufacturers likely made the jugs. However, this alone was not enough information to draw any conclusions. There are other Jewish companies in Leadville that sold liquor, either wholesale or retail, as well as non-Jewish companies, but the museum does not own any examples these jugs.

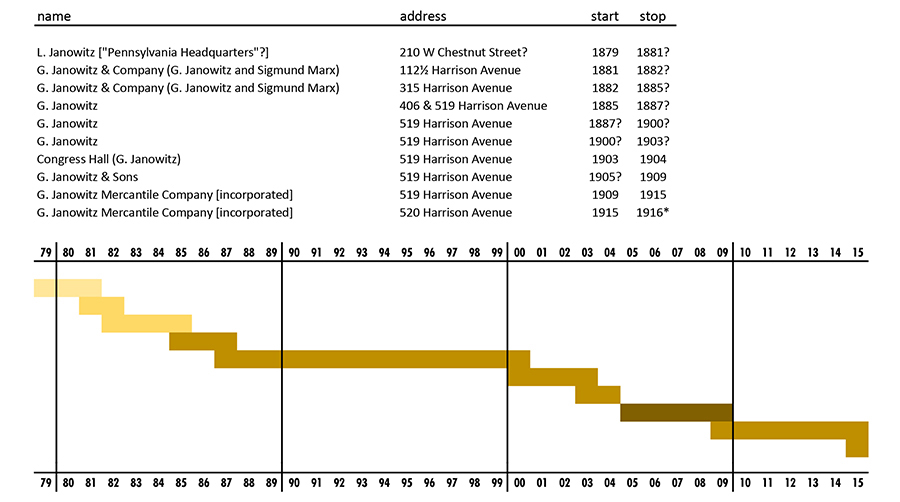

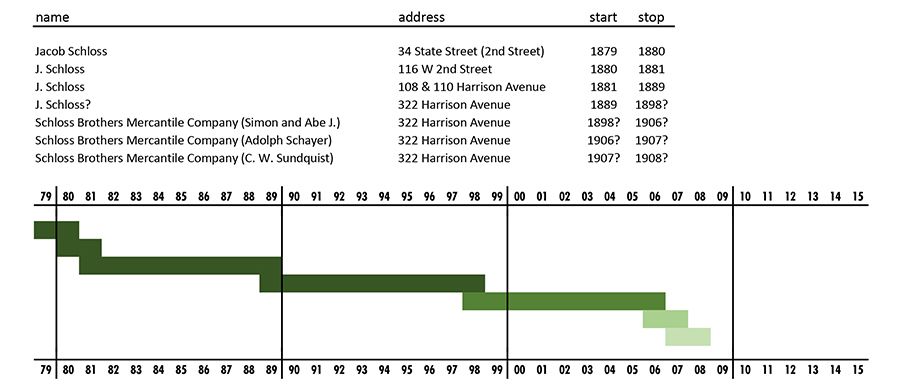

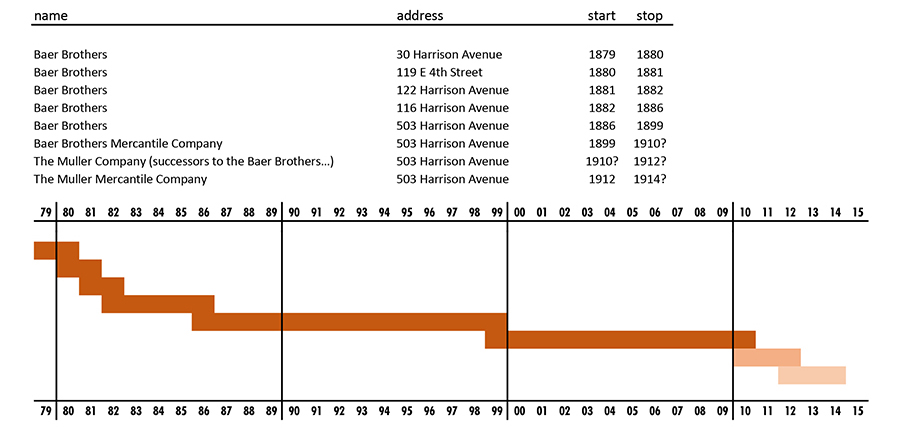

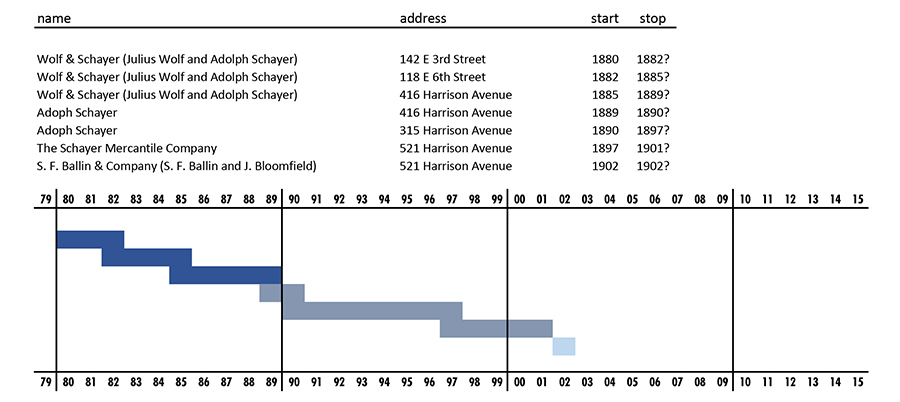

The next step was to determine how to get more specific dates for each company. Fortunately, this was easier than initially expected and proved key to immediately narrowing down the dates for most of the companies. Using the Leadville city directories and making a list year by year of the surnames for the companies of which we have jugs gave enough information to organize the companies into a timeline (see graphics below). This gave a breakdown of the different locations of each business, who owned each company and when, and even provided a succession of company ownership. This progression of company names and owners revealed that of the companies where the museum has jugs only four distinct runs of businesses existed with varying names.

Progression of the Janowitz liquor business.

Progression of the Schloss liquor business.

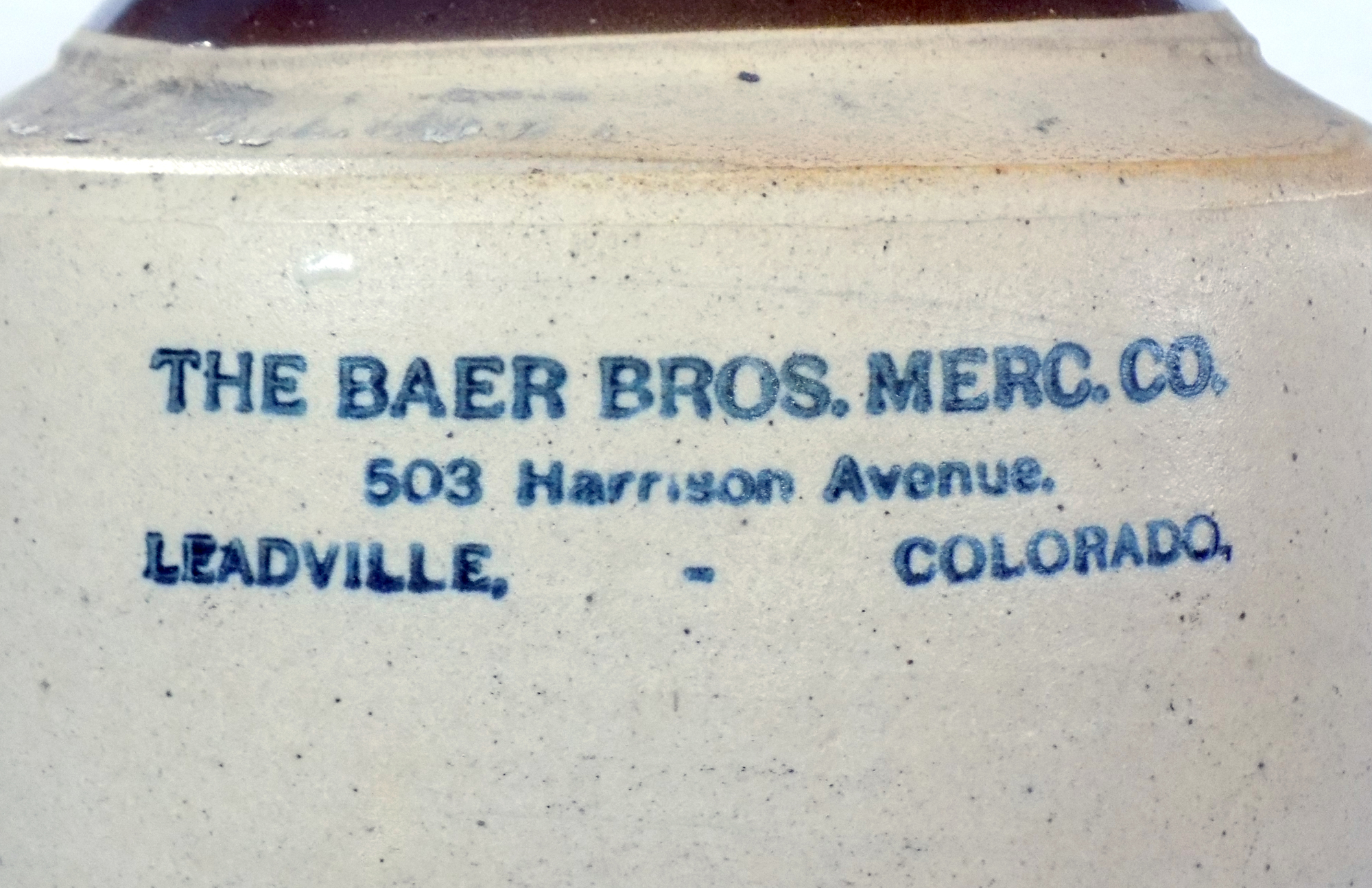

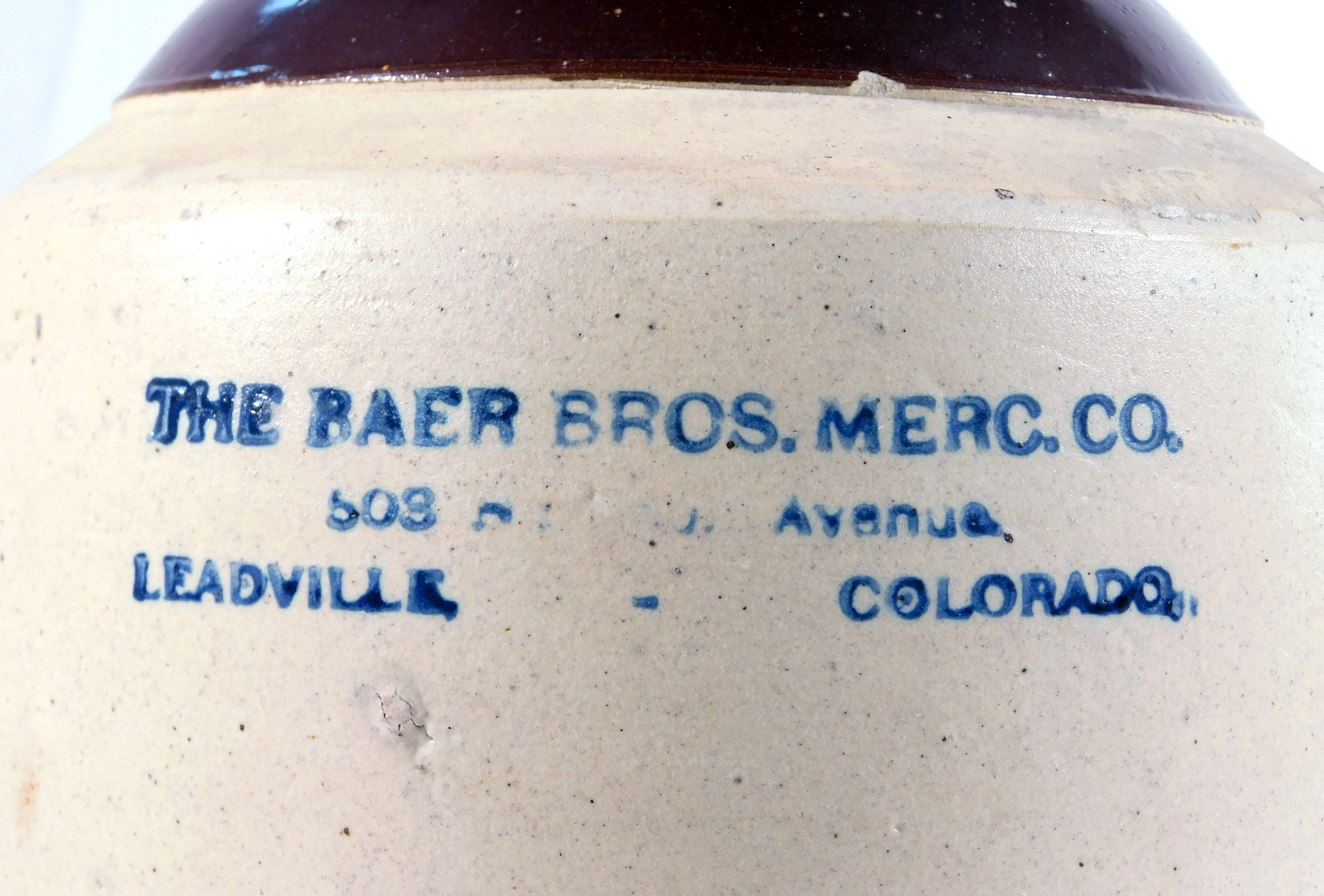

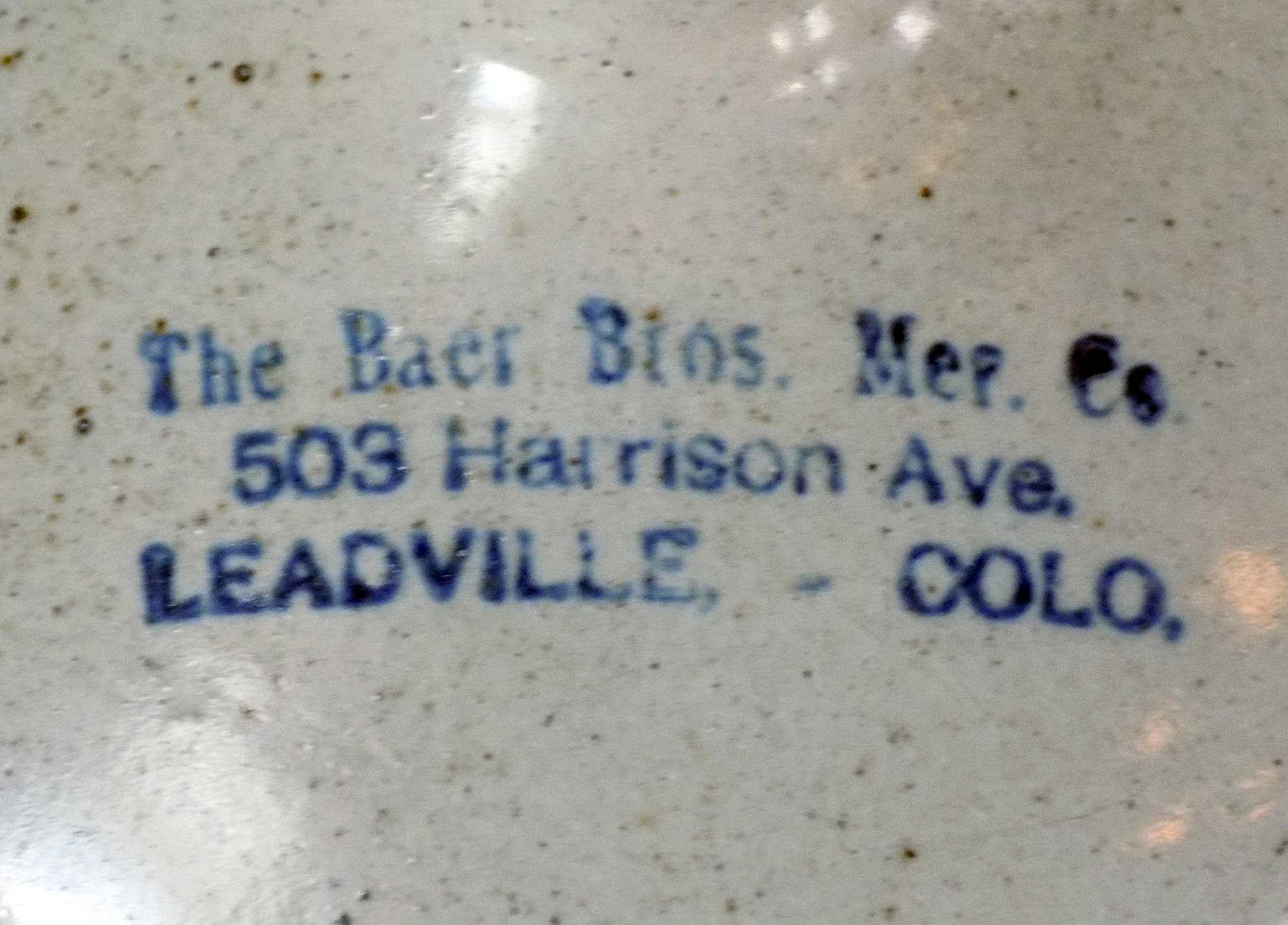

Progression of the Baer liquor business.

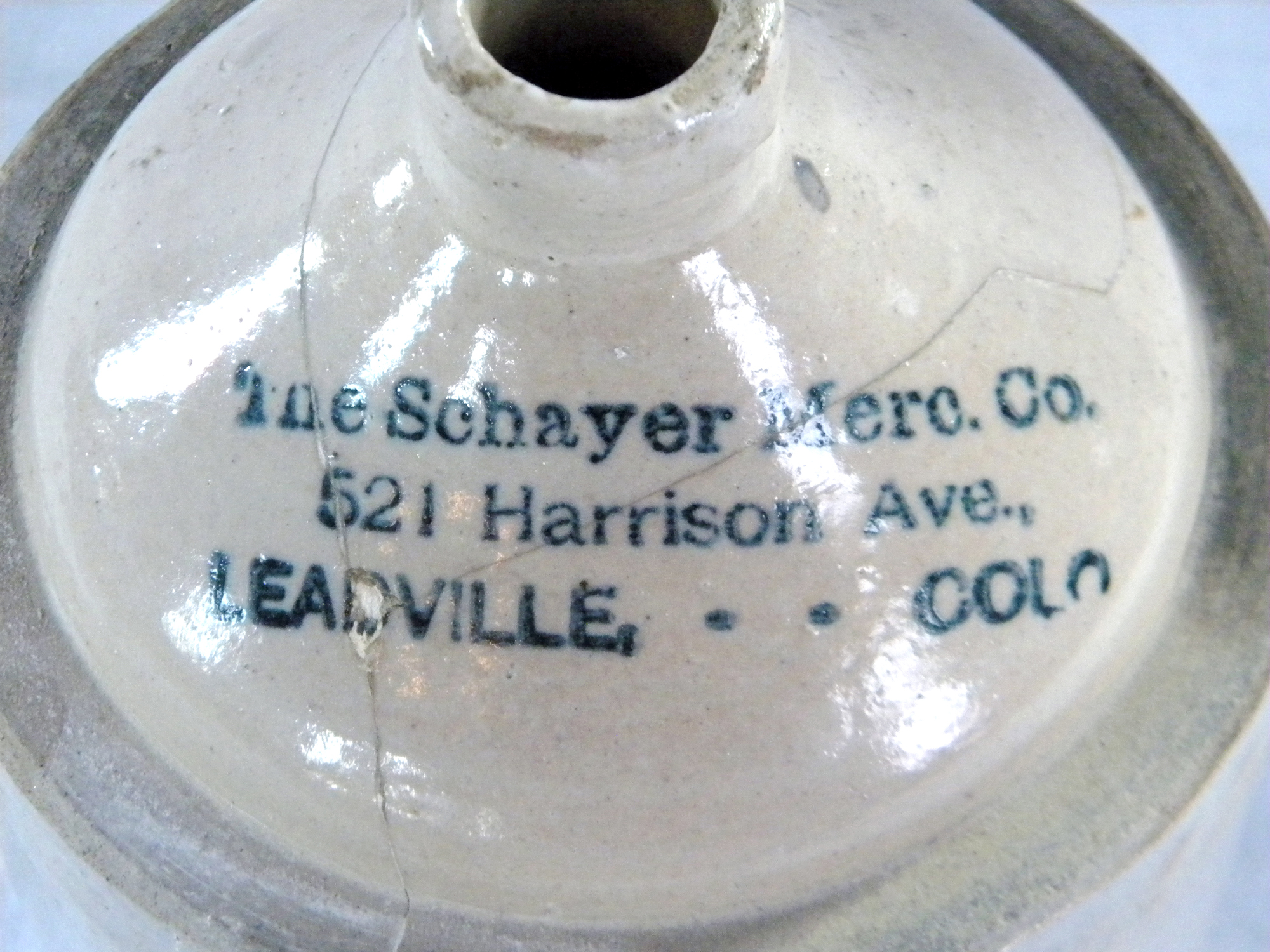

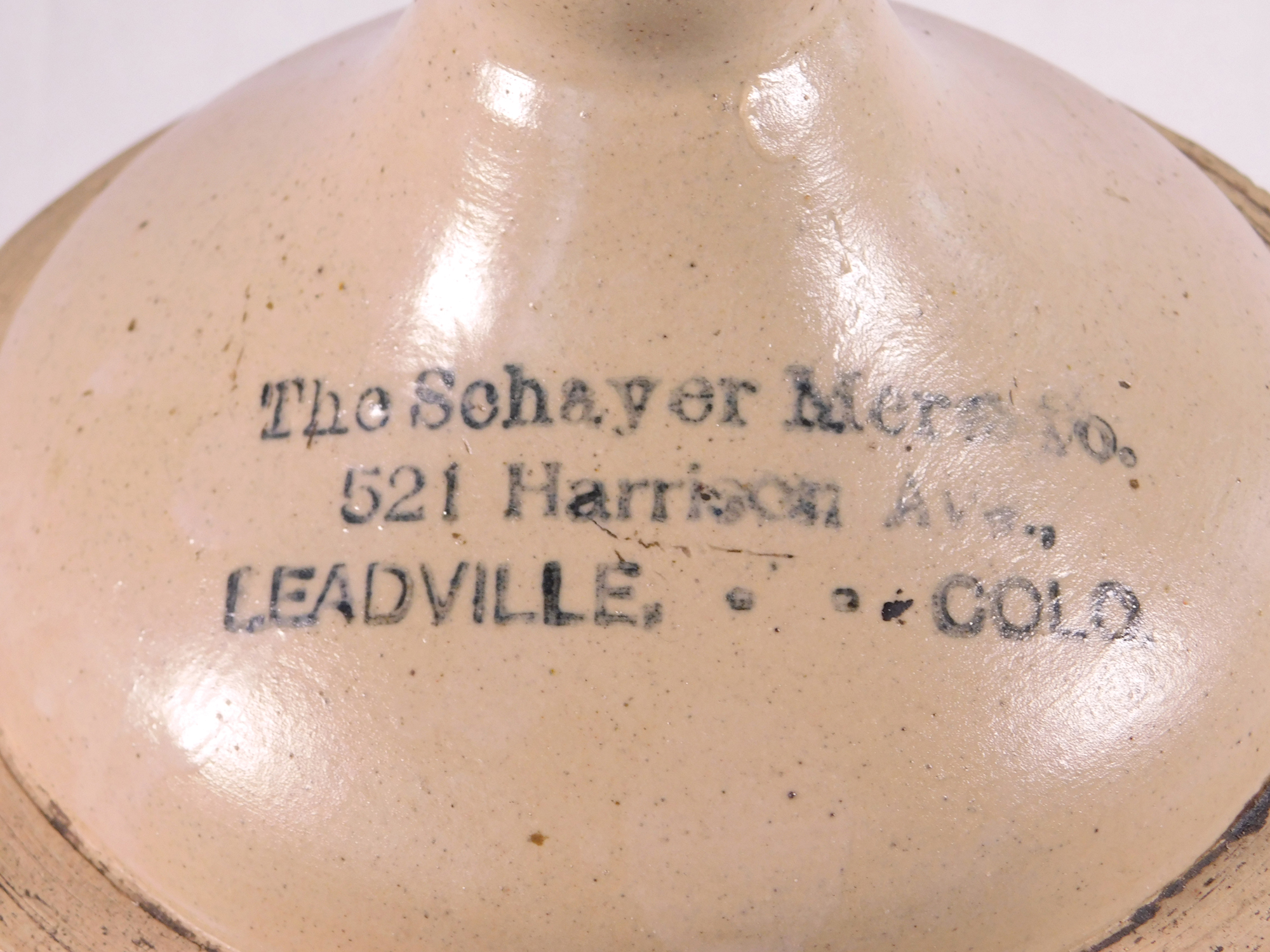

Progression of the Schayer liquor business.

The specific names and addresses on the jugs were then matched to the list and immediately provided a narrower date range. However, some companies had consistent names and addresses on the jugs for many years, specifically Schloss Brothers, noting that the styles of the jugs varied over time even if the business name did not. It is important to note that Colorado prohibition started on January 1, 1916, [1] four years ahead of the national prohibition that started on January 17, 1920 [3] when the Volstead Act went into effect. Therefore, all liquor companies ceased liquor sales sometime before the end of 1915, even if the company continued to exist beyond 1915 in a capacity that did not sell liquors.

The next step in the process was to determine a way to identify the makers of the jugs and perhaps show specific date ranges for when each jug style was in use. Certainly, this was a much harder process! Initially, the museum’s jugs were sorted by their similar type, which resulted in approximately three different general styles, with one style being greatly different from the others. Two of the styles needed rethinking and were resorted using other criteria (more on that later). Because the museum only has the 30+ jugs, this was not enough quantities of each type to determine an accurate set of examples. More jugs were needed to get a better grouping sample. Fortunately, a man named David Clint worked with the Antique Bottle Collectors of Colorado in the 1970s to assemble an exhaustive book for identifying bottles, jugs, and some additional information. Not only did he include the liquor wholesalers and retailers in Colorado, he also included the companies who made the containers. The book is called Colorado Historical Bottles & Etc., 1859-1915. [2]

This book focuses more on glass bottles, but it still had a sizable pottery jug section, which included images, information, and dates about most of the liquor companies in Colorado. Compiling the relevant information into a spreadsheet (refer to the PDF download of this complete report) helped establish the spread of the jugs styles across the state and could help determine specific dates of use, which hopefully could help better identify the companies that made them. This research showed an overwhelming similarity of the Colorado jugs to those of the Leadville companies. Many of the other Colorado liquor companies were only in business for a short time and helped to give some specific dates for specific jug styles. Because the Schloss Brothers company used several different styles of jugs over the course of the business, determining the order or sequence or coinciding use of the jugs is harder to determine.

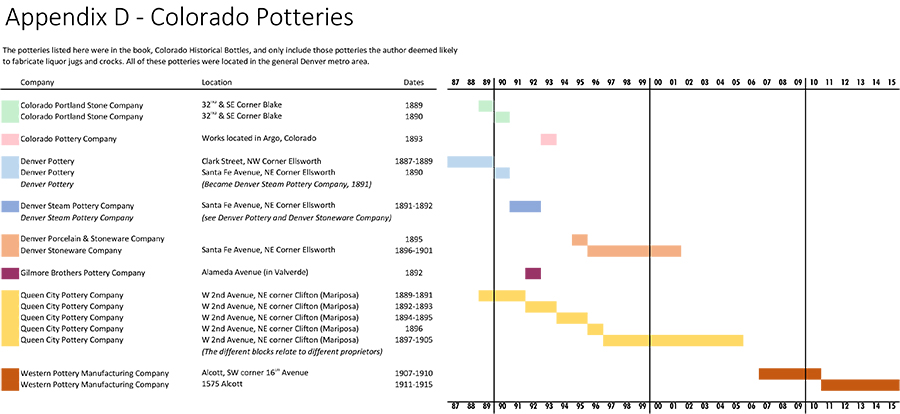

The book provided a researched list of pottery manufacturers in Colorado, mostly in the Denver area, that likely made the jugs shown in the book. The book states that the ones in the list were the most consistent for the type of clay typically used for crocks and jugs. (See below for the list assembled by Clint.) Certainly, many other potteries existed in various places across the United States and certainly any company could have gone with any supplier no matter where it was located and have the jugs shipped by rail and wagon. However, it makes good economic sense, especially for that time period, that a company would use a supplier local to its region for a lower cost and quicker manufacturer and delivery time. In addition, it is likely that salesmen [4] of these manufacturers would try to drum up business by going to liquor companies to gain business, a common practice with companies of that time period (see Appendix E for an article referencing this). This is likely why so many of the jugs appeared identical among the various companies across the state. With some assumption, this research will use the Colorado potteries as the likely source for most of the jugs.

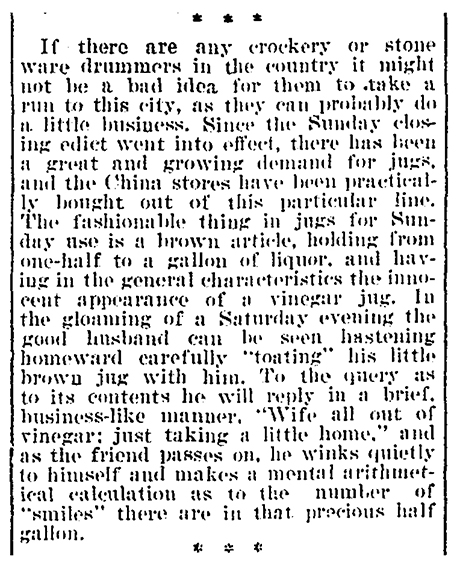

If there are any crockery or stone ware drummers in this country it might not be a bad idea for them to take a run to this city, as they can probably do a little business. Since the Sunday closing edict went into effect, there has been a great and growing demand for jugs, and the China stores have been practically bought out of this particular line. The fashionable thing in jugs for Sunday use is a brown, article, holding from one-half to a gallon of liquor, and having in the general characteristics the innocent appearance of a vinegar jug. In the gloaming of a Saturday evening the good husband can be seen hastening homeward carefully “toating” [toting] his little brown jug with him. To the query as to its contents he will reply in a brief, business-like manner. “Wife all out of vinegar: just taking a little home.” and as the friend passes on, he winks quietly to himself and makes a mental arithmetical calculation as to the number of “smiles” there are in that precious half gallon.

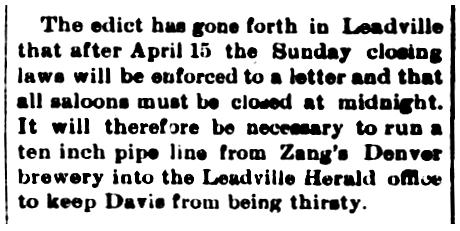

The edict has gone forth in Leadville that after April 15 the Sunday closing laws will be enforced to a letter and that all saloons must be closed at midnight. It will therefore be necessary to run a ten inch pipe line from Zang’s Denver brewery into Leadville Herald office to keep [C.C.] Davis from being thirsty.

The type of material that crocks and liquor jugs were made is generally referred to as stoneware, and specifically American stoneware. This is a type of clay fired in kilns reaching 2192°F to 2399°F. The high firing creates a higher vitrification that makes the clay essentially waterproof. However, the crocks and jugs were still coated in a glaze which is good for cleanliness as well as ease of cleaning. Refer to the end of this page for general information about jug fabrication from personal clay working experience.

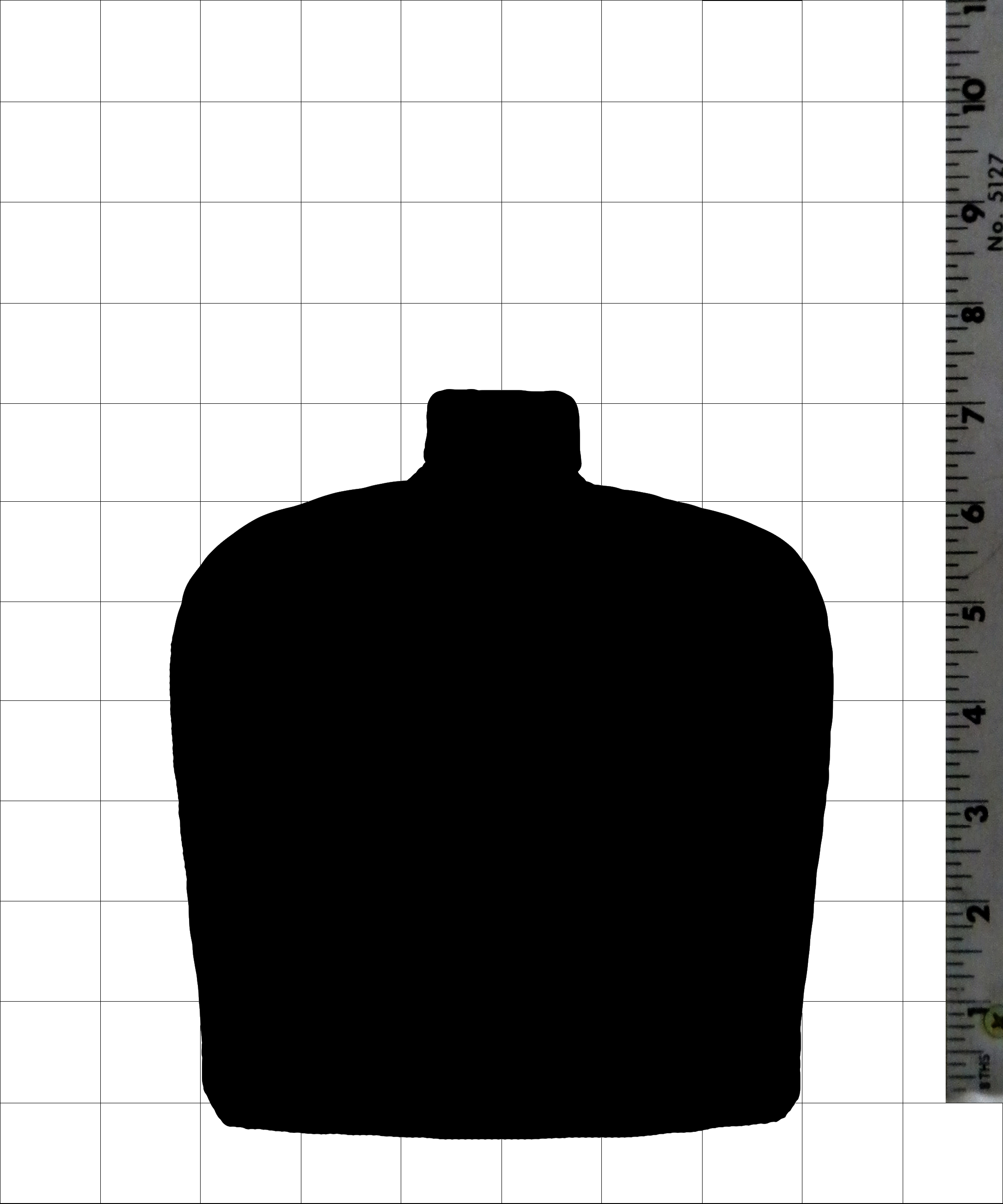

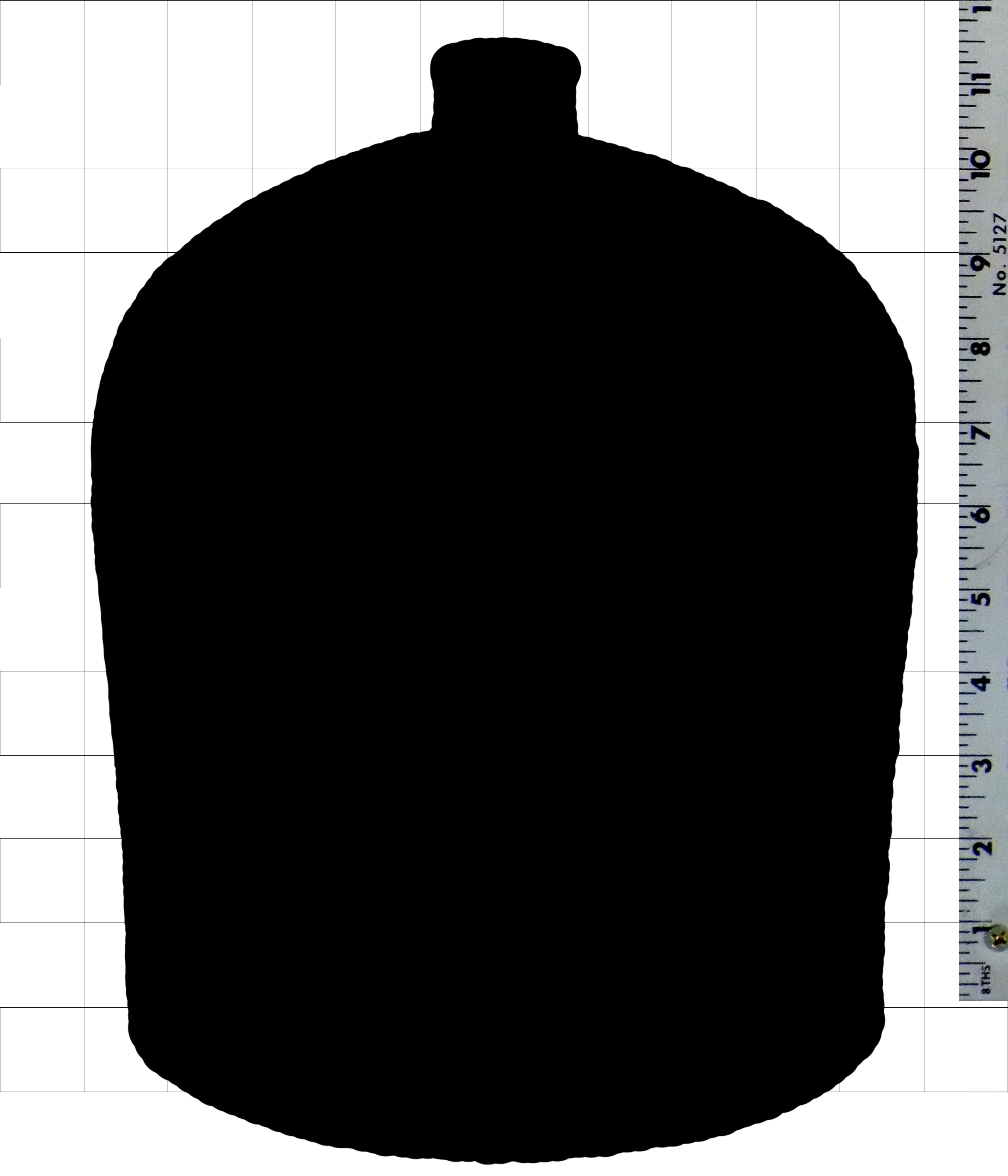

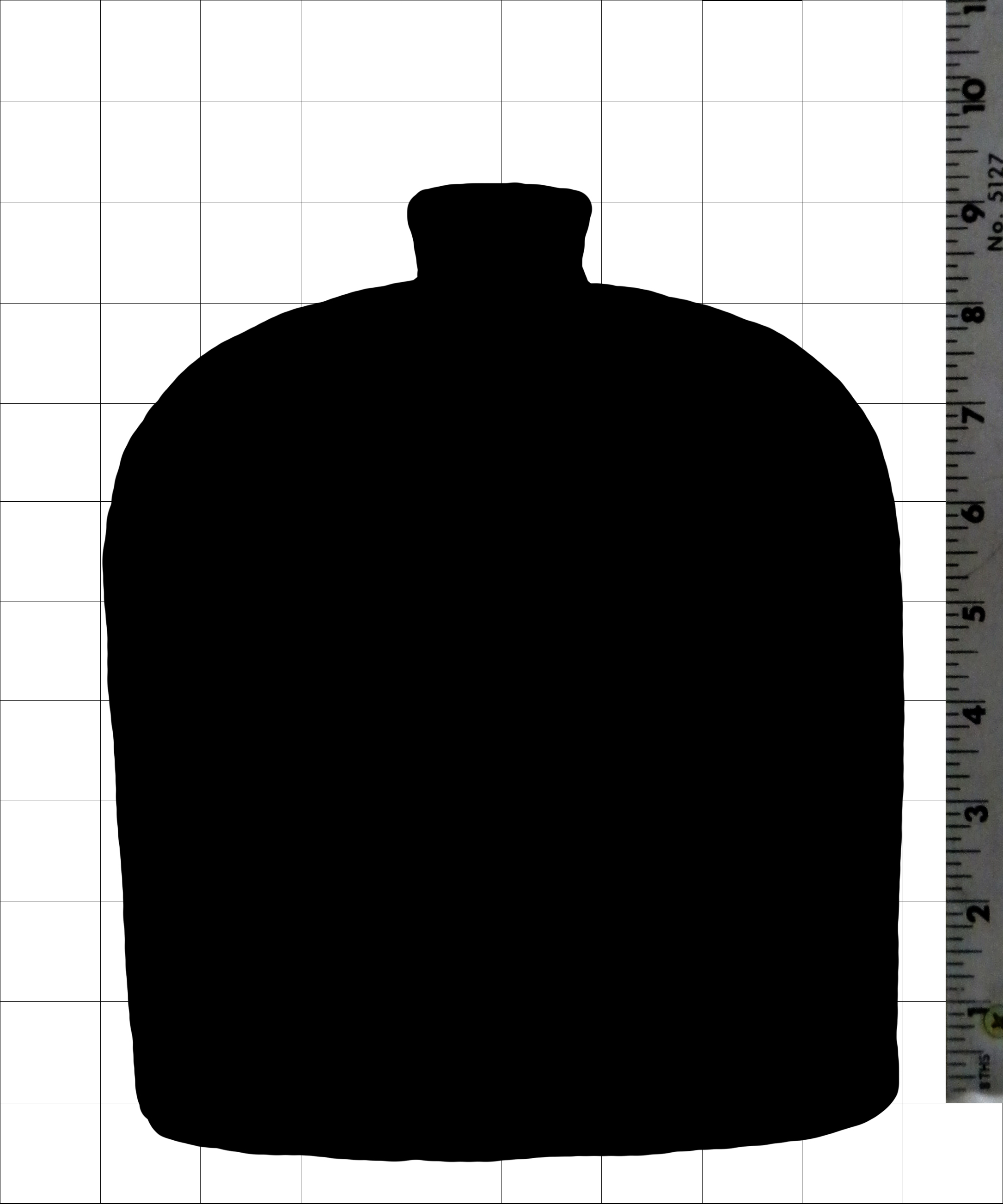

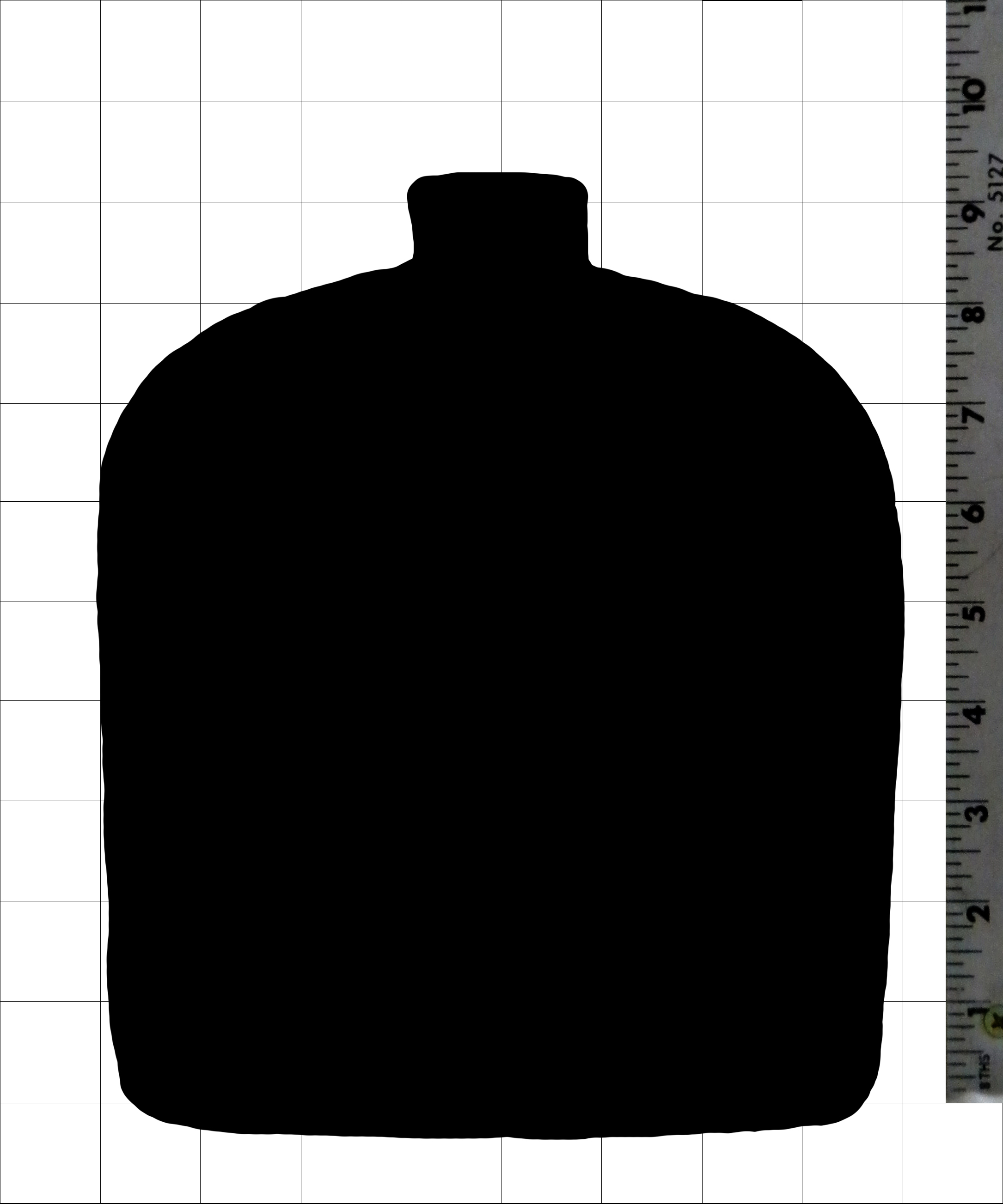

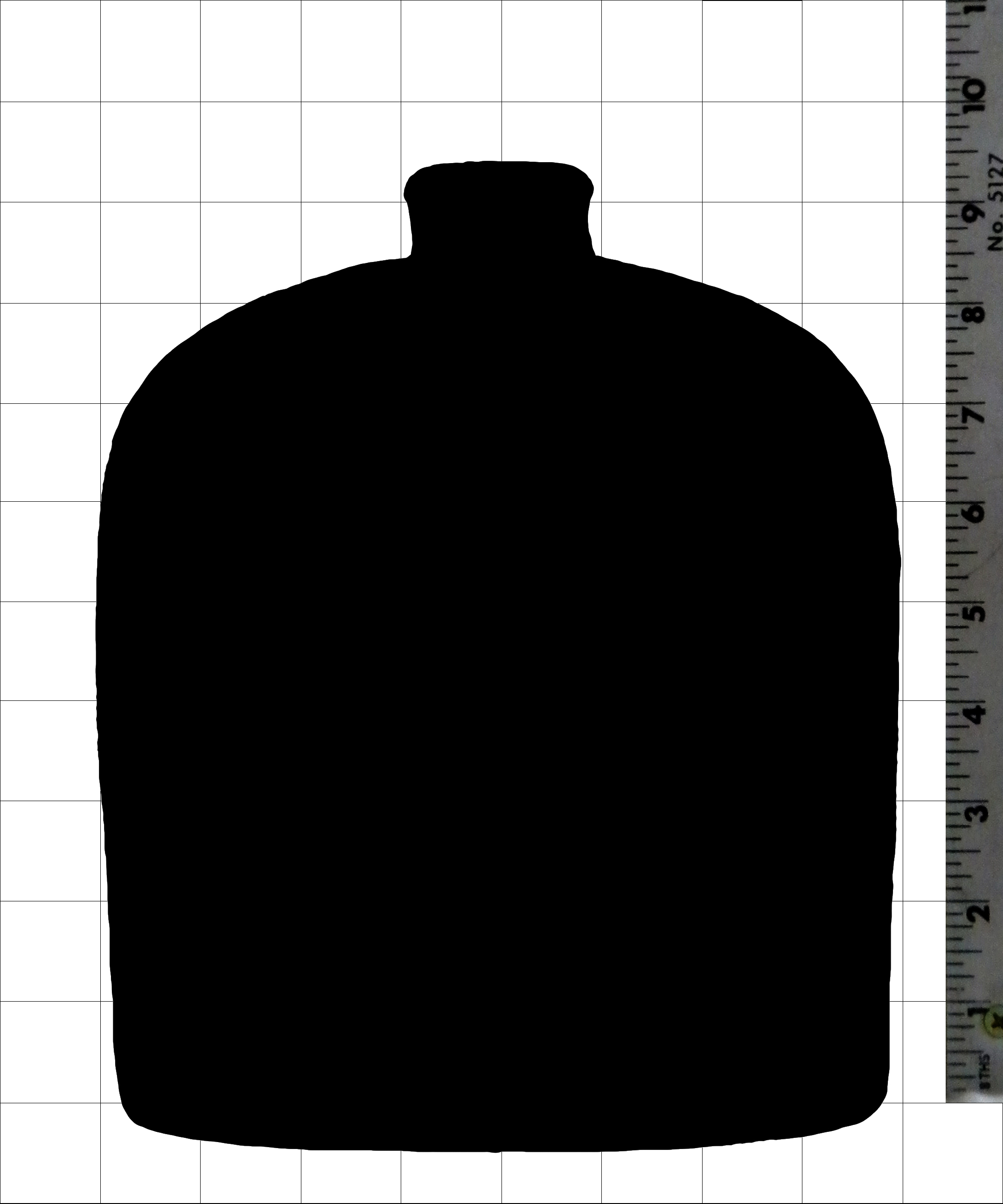

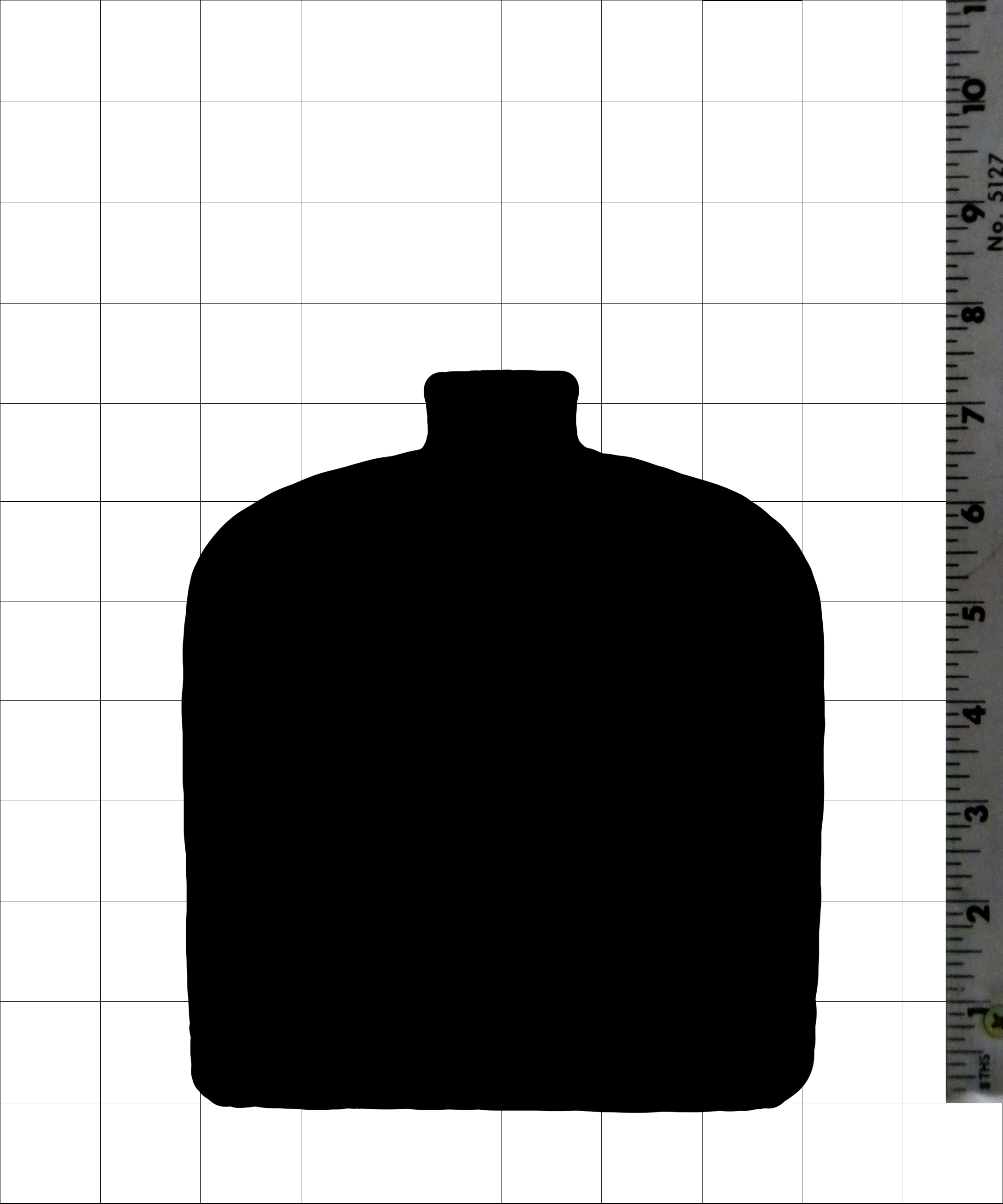

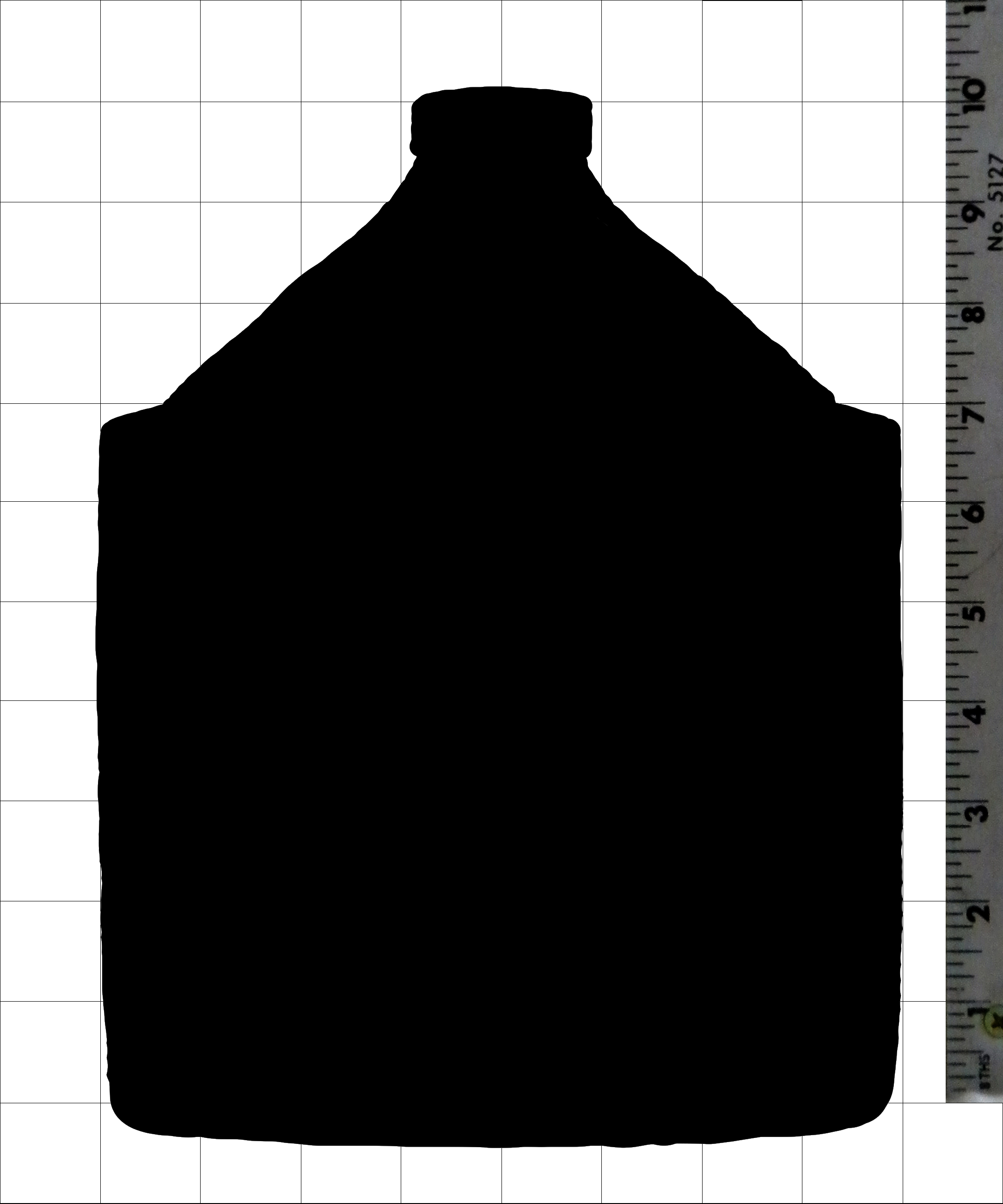

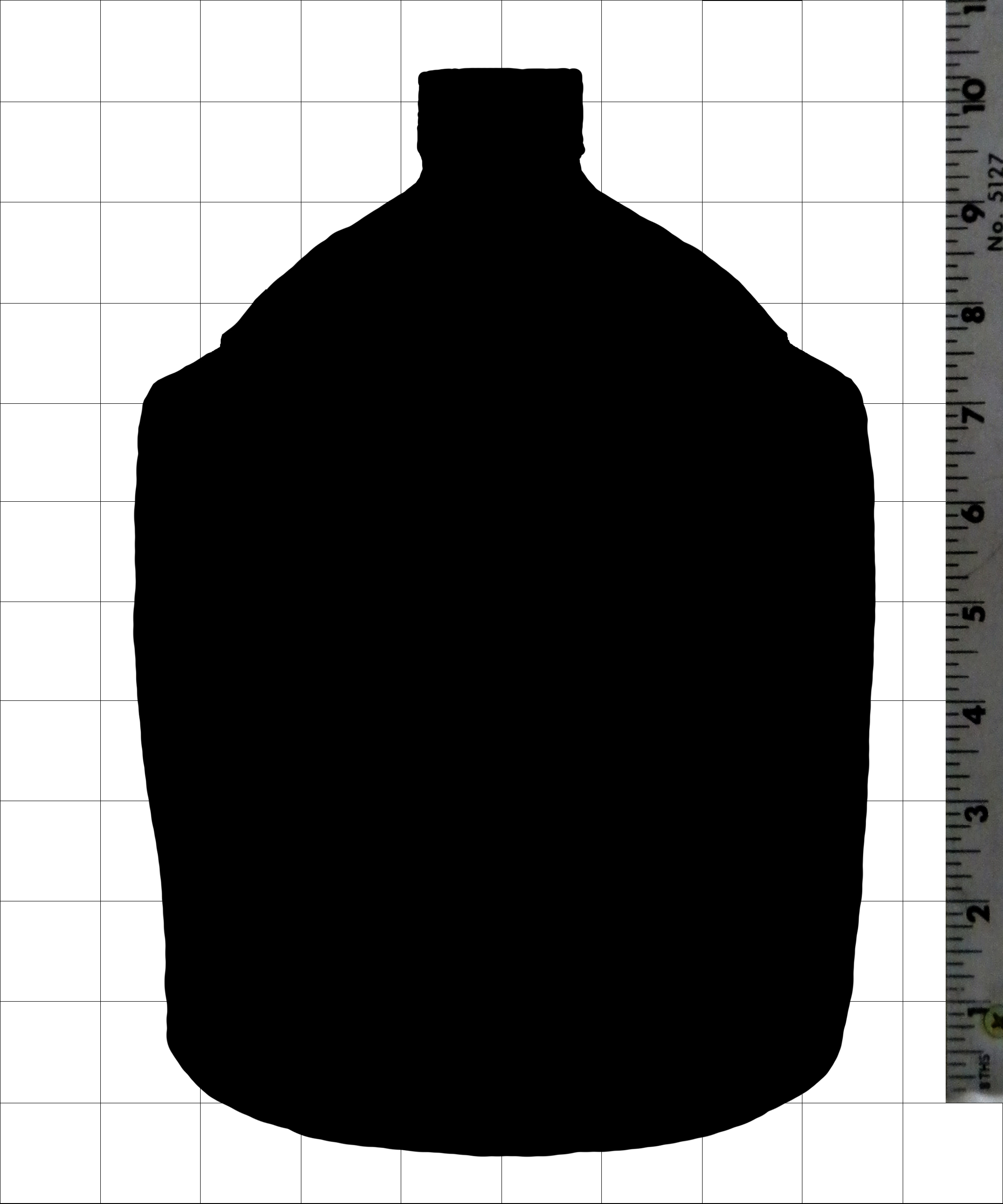

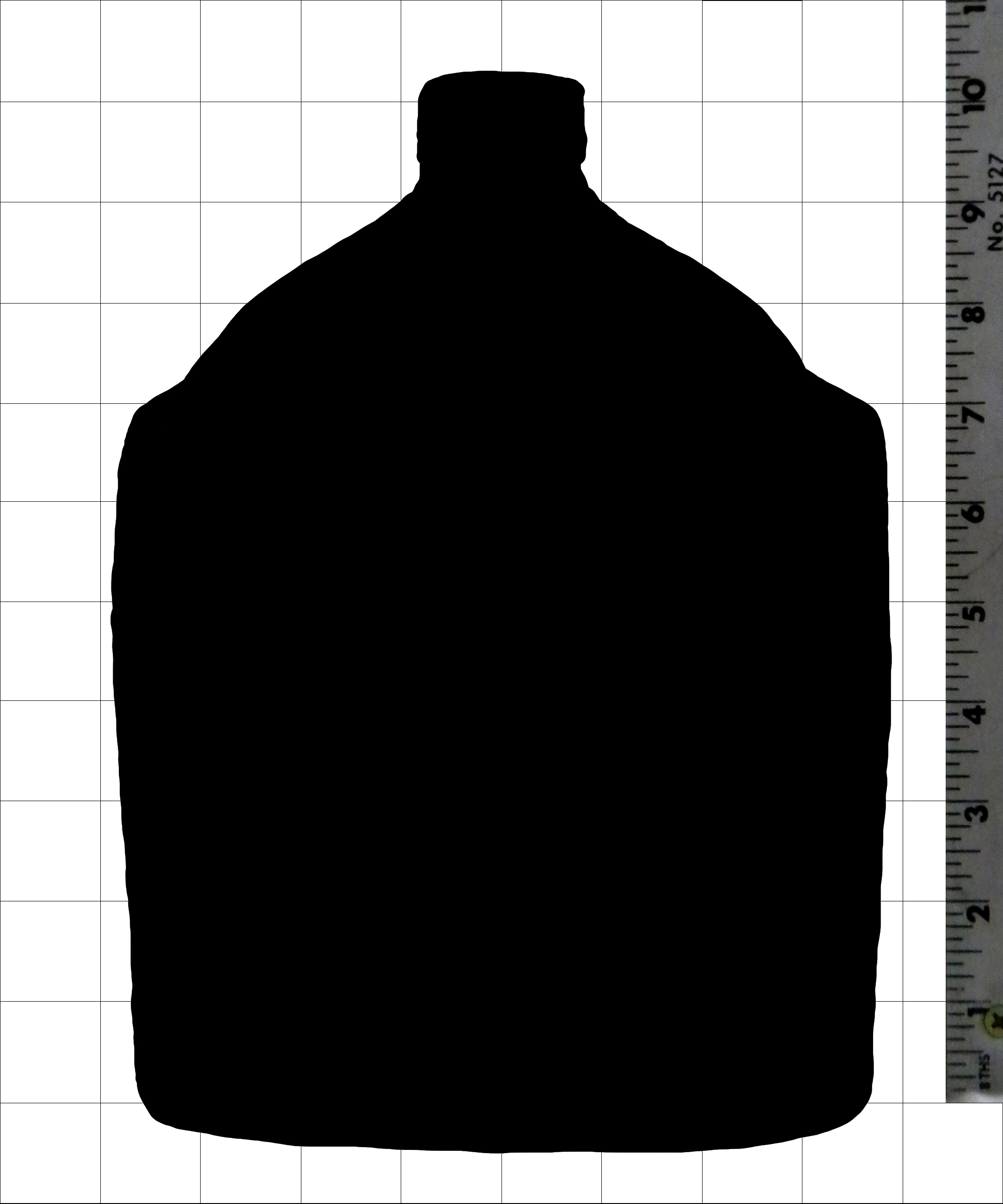

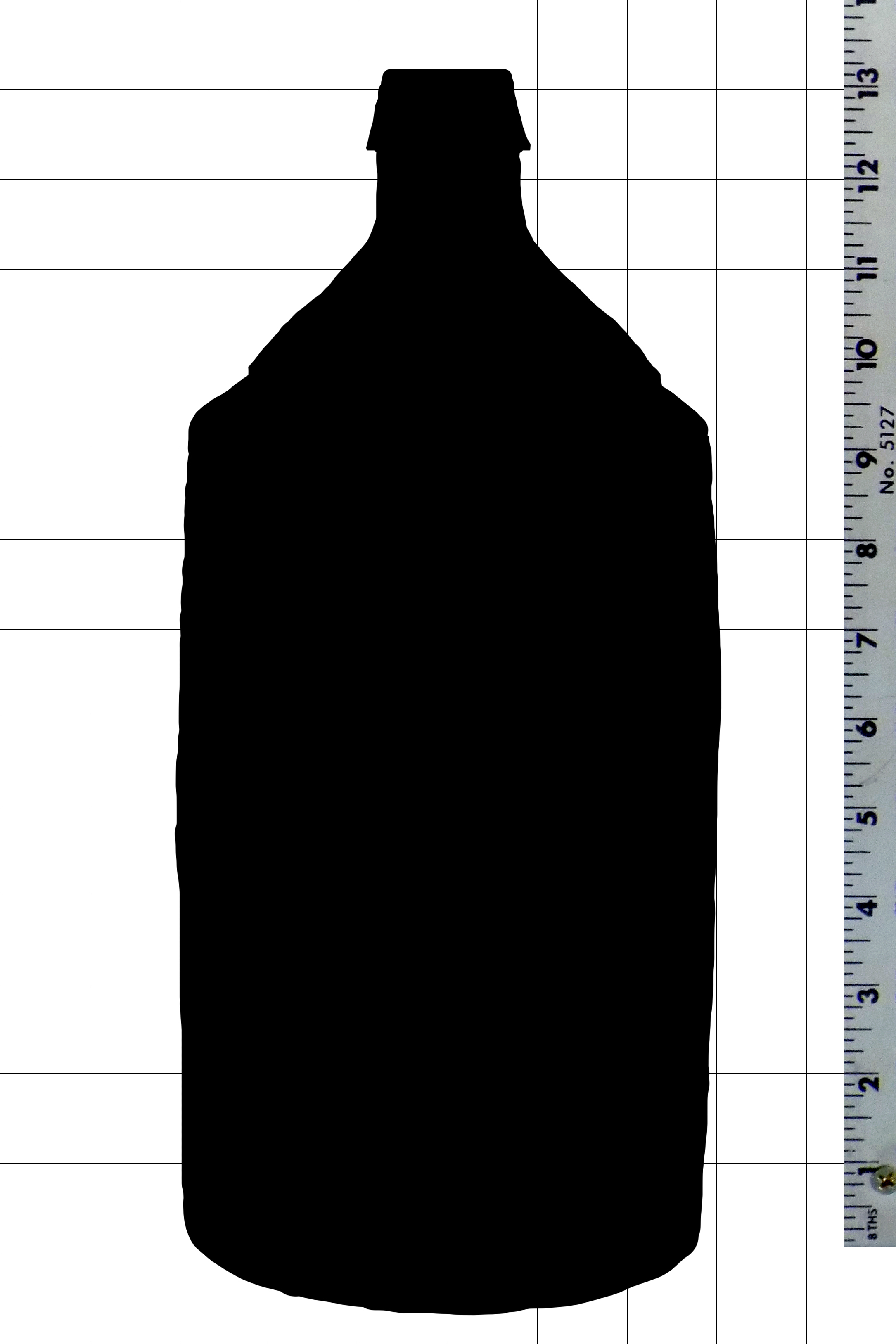

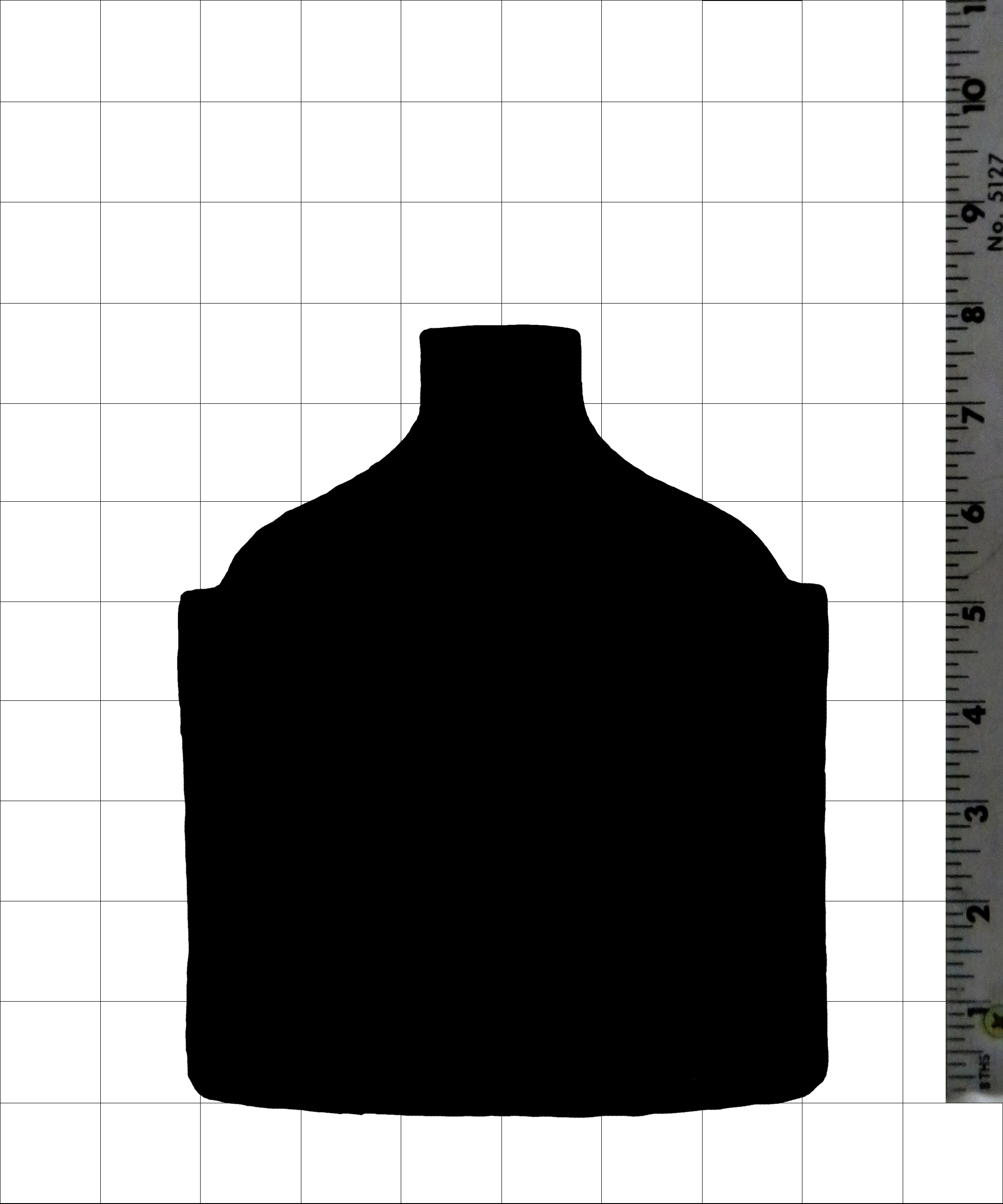

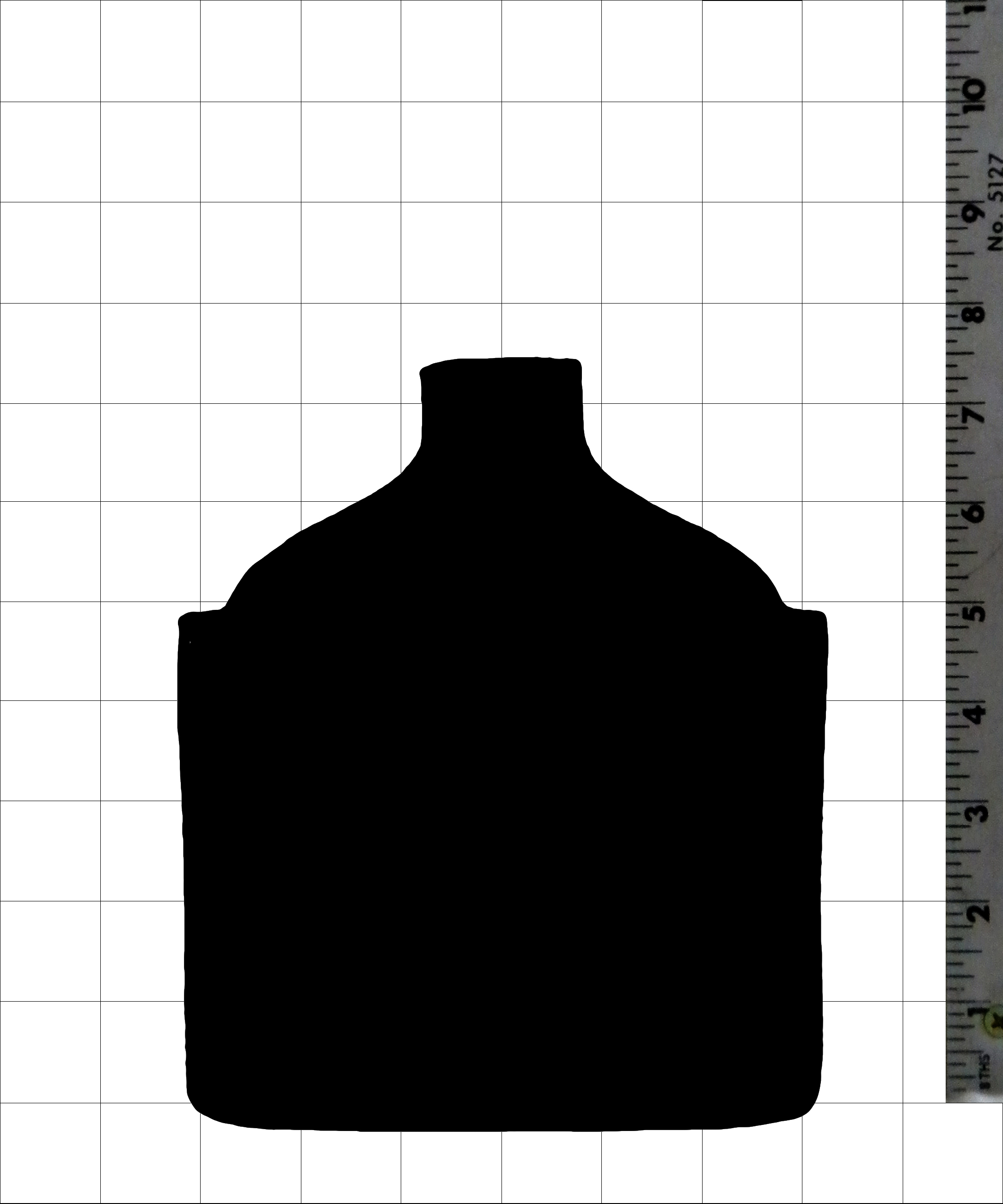

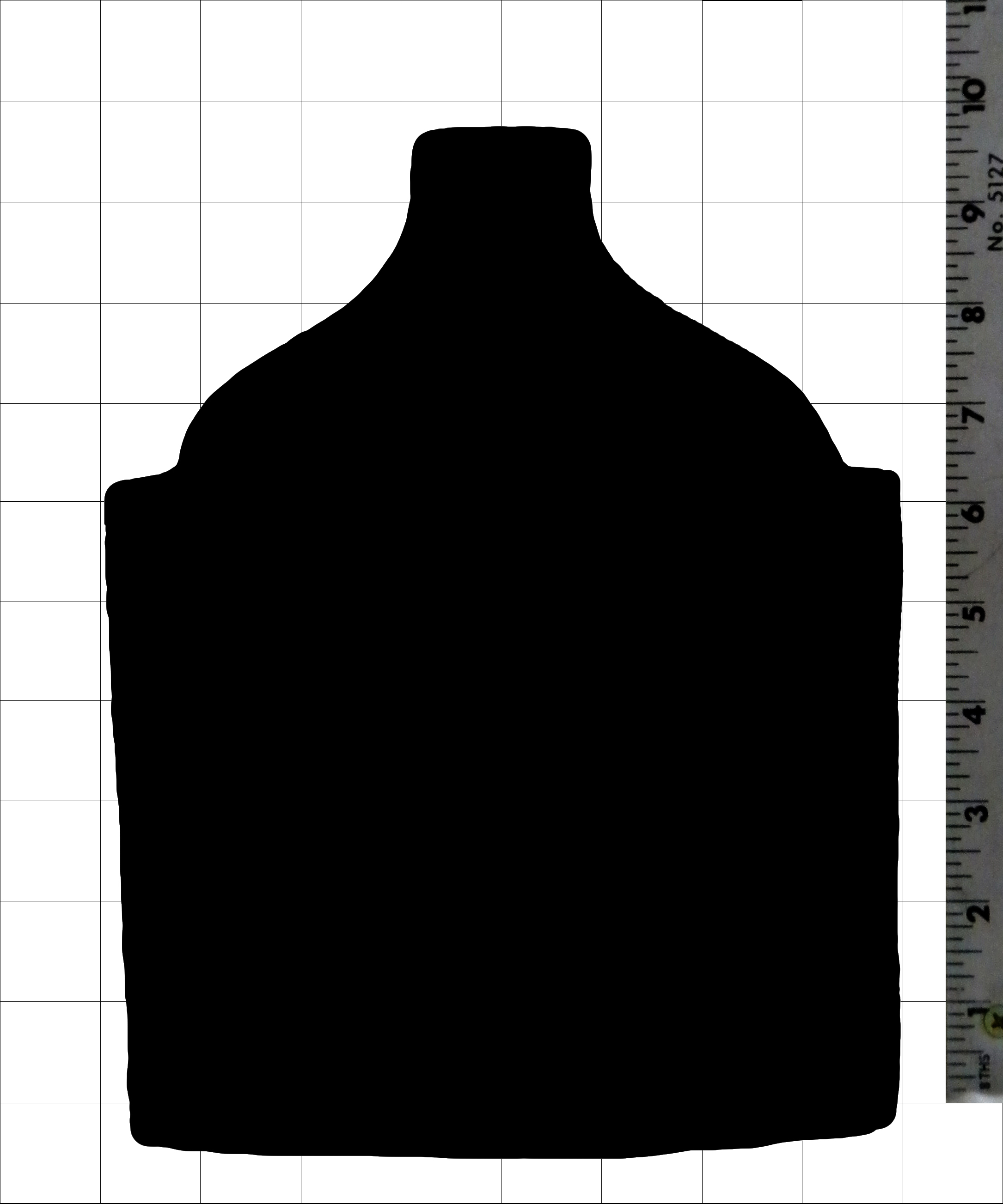

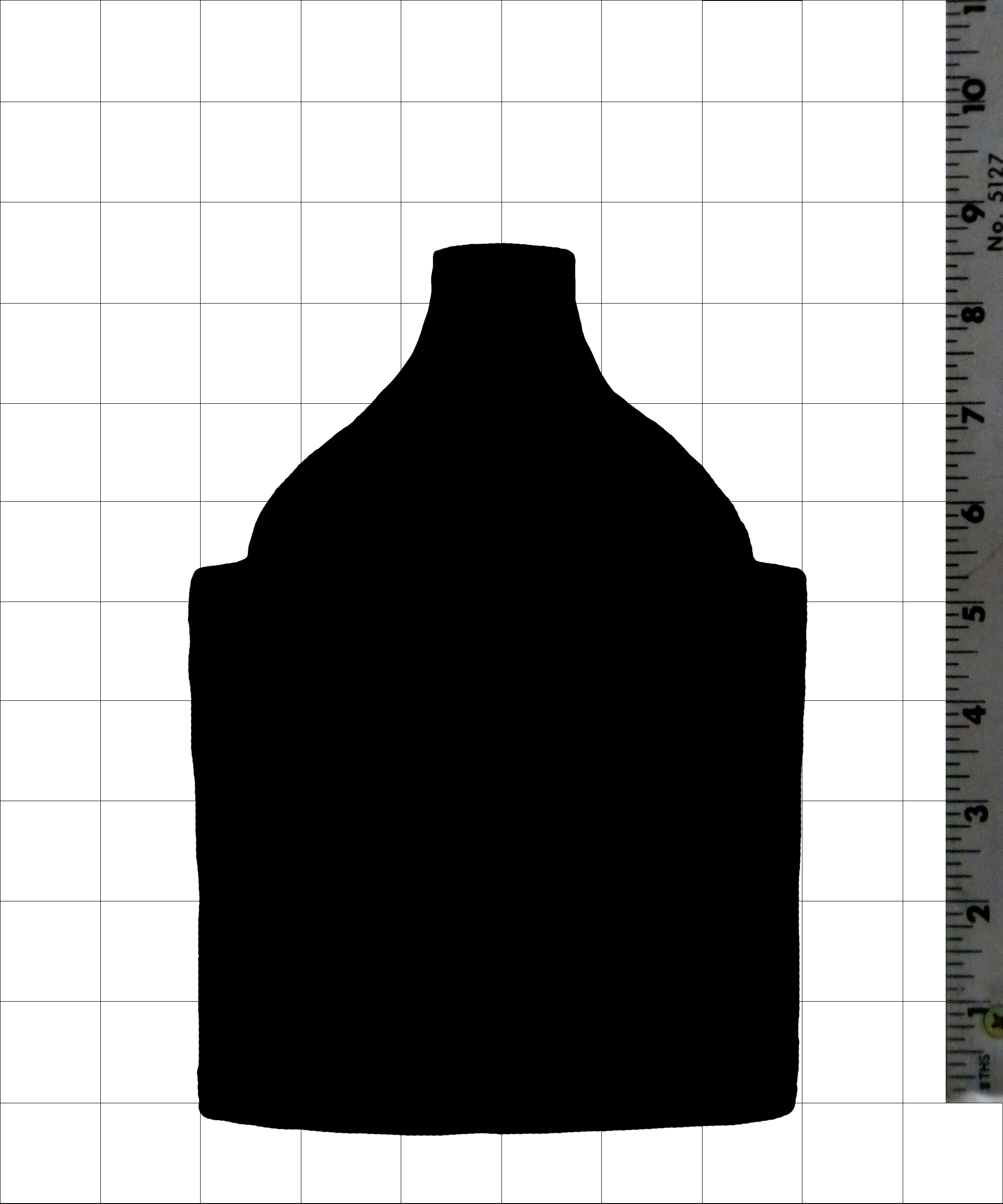

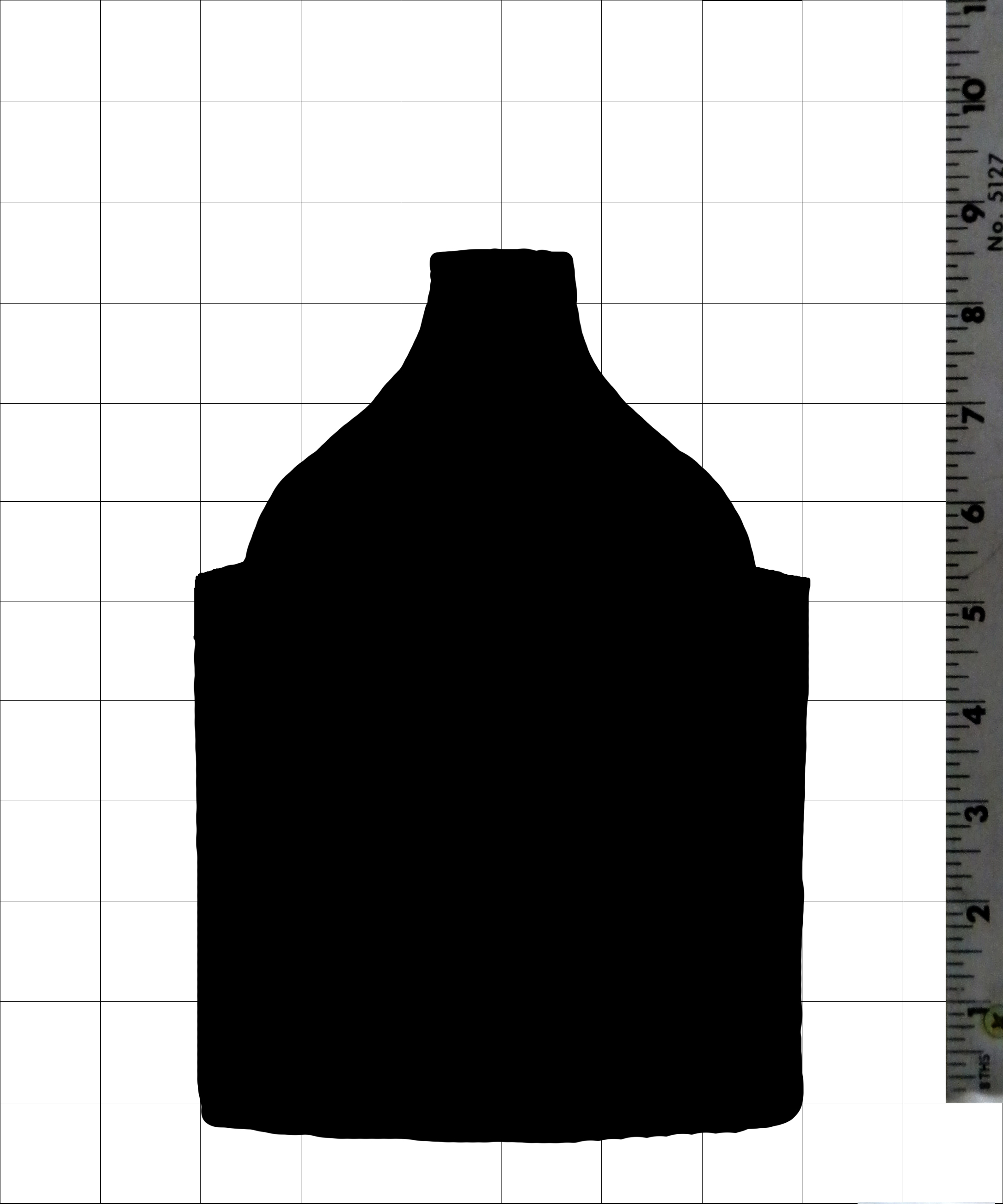

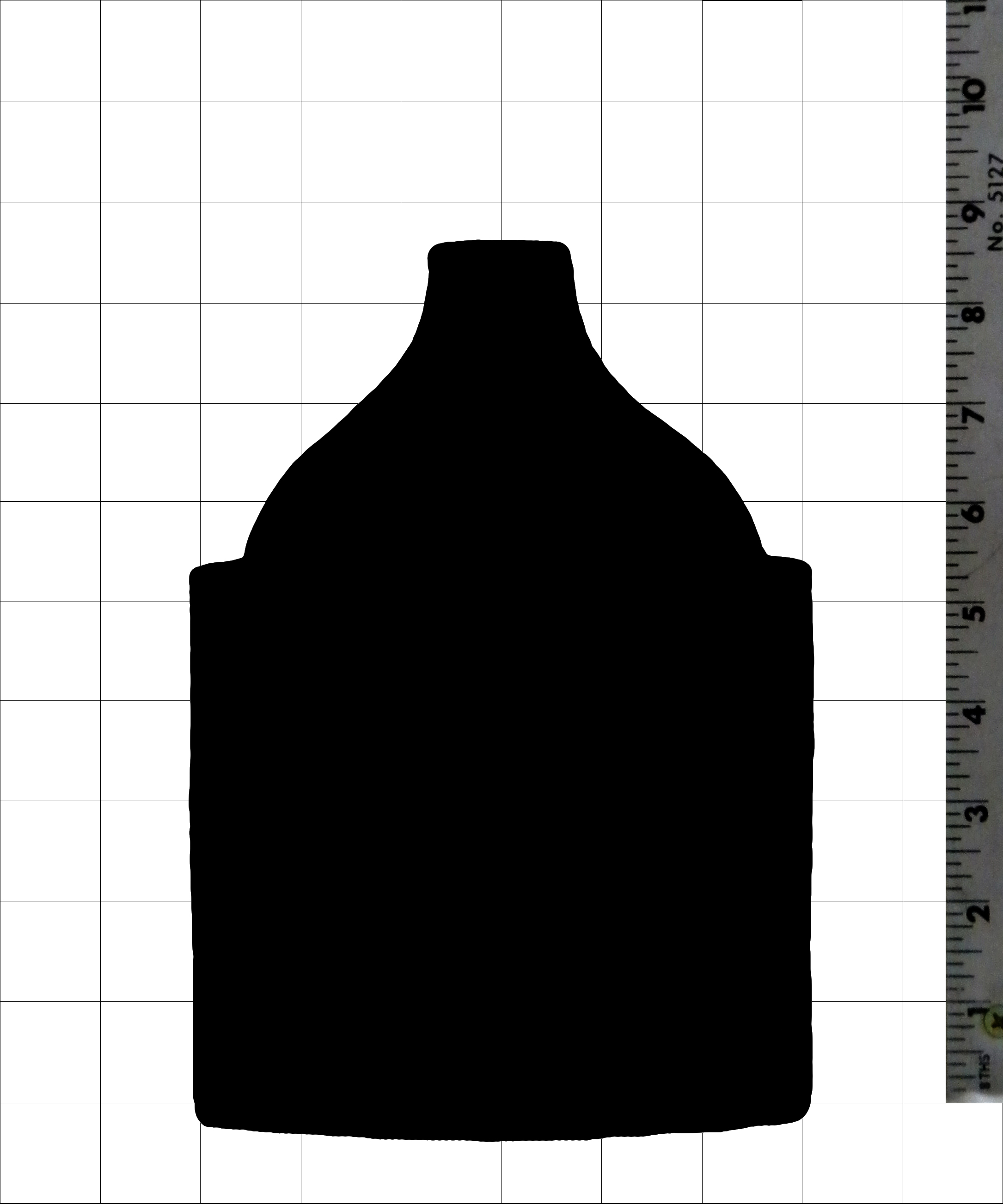

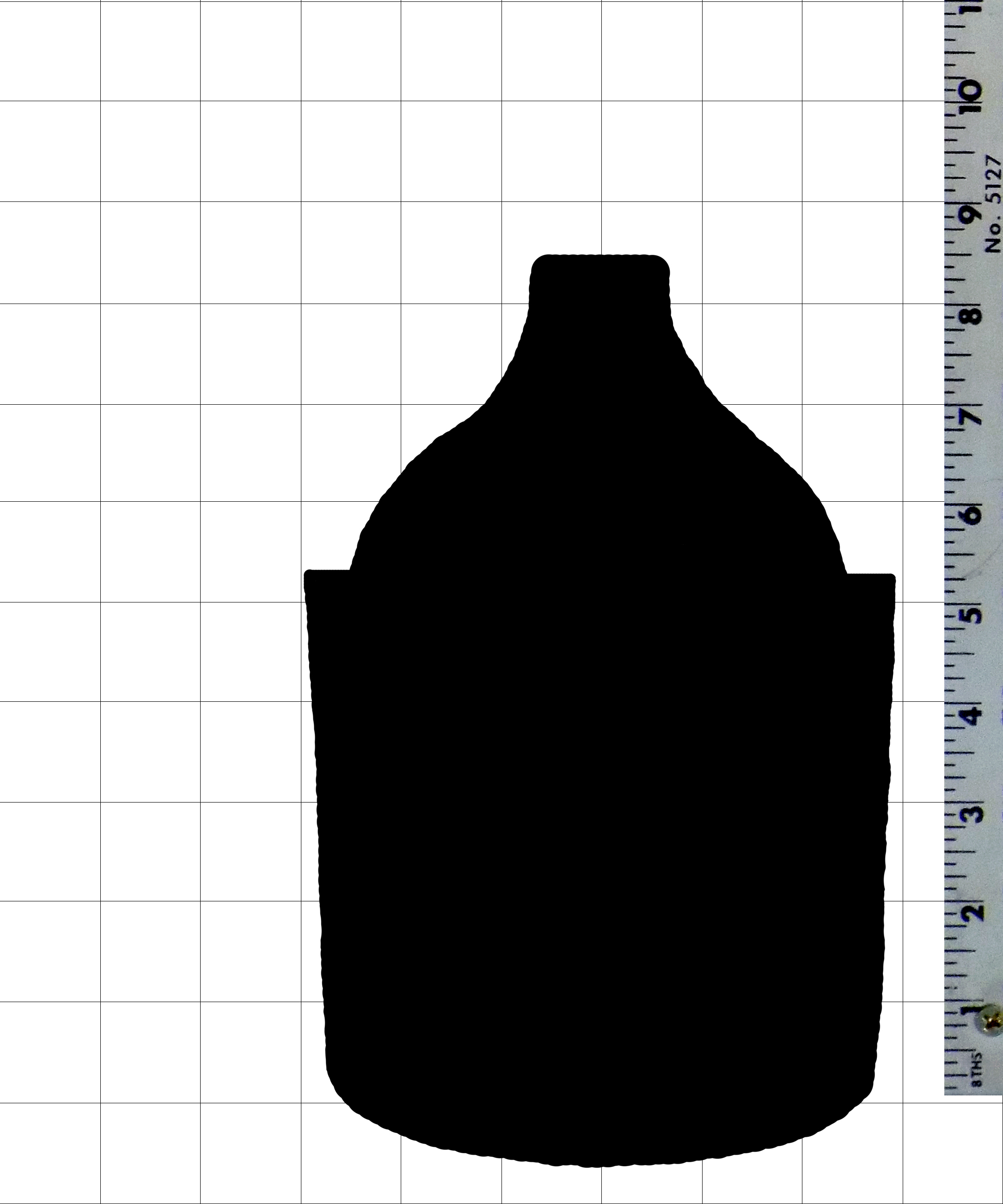

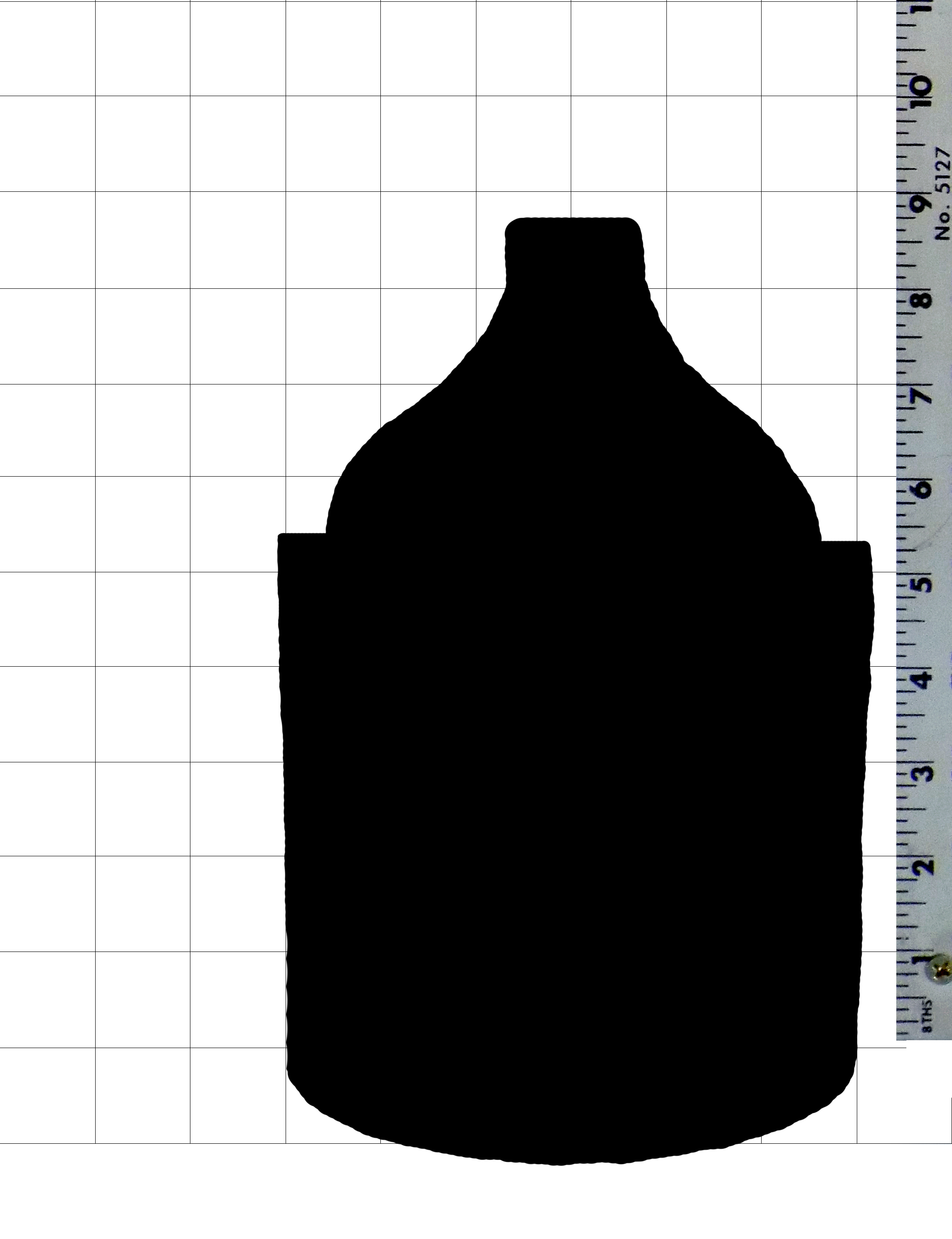

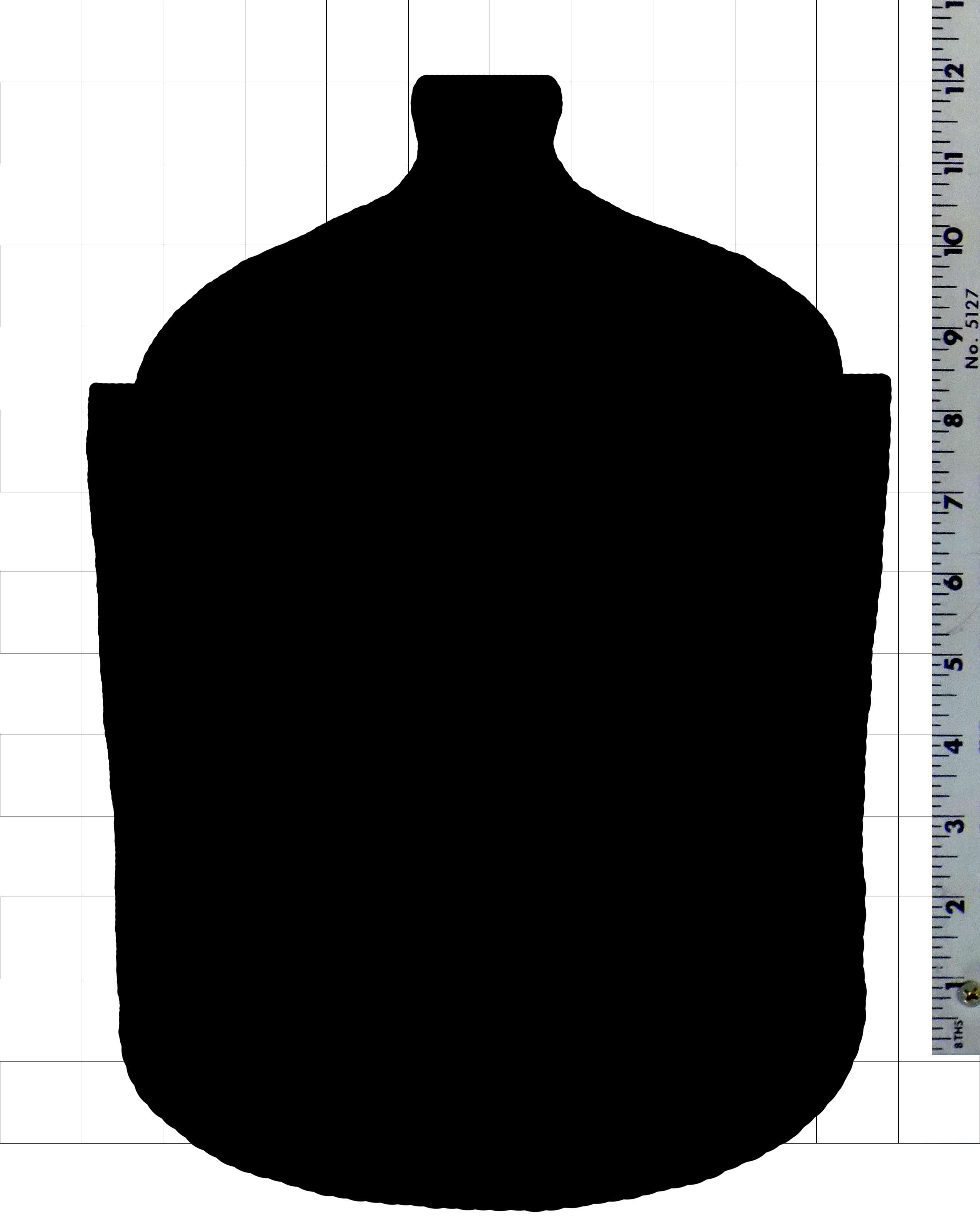

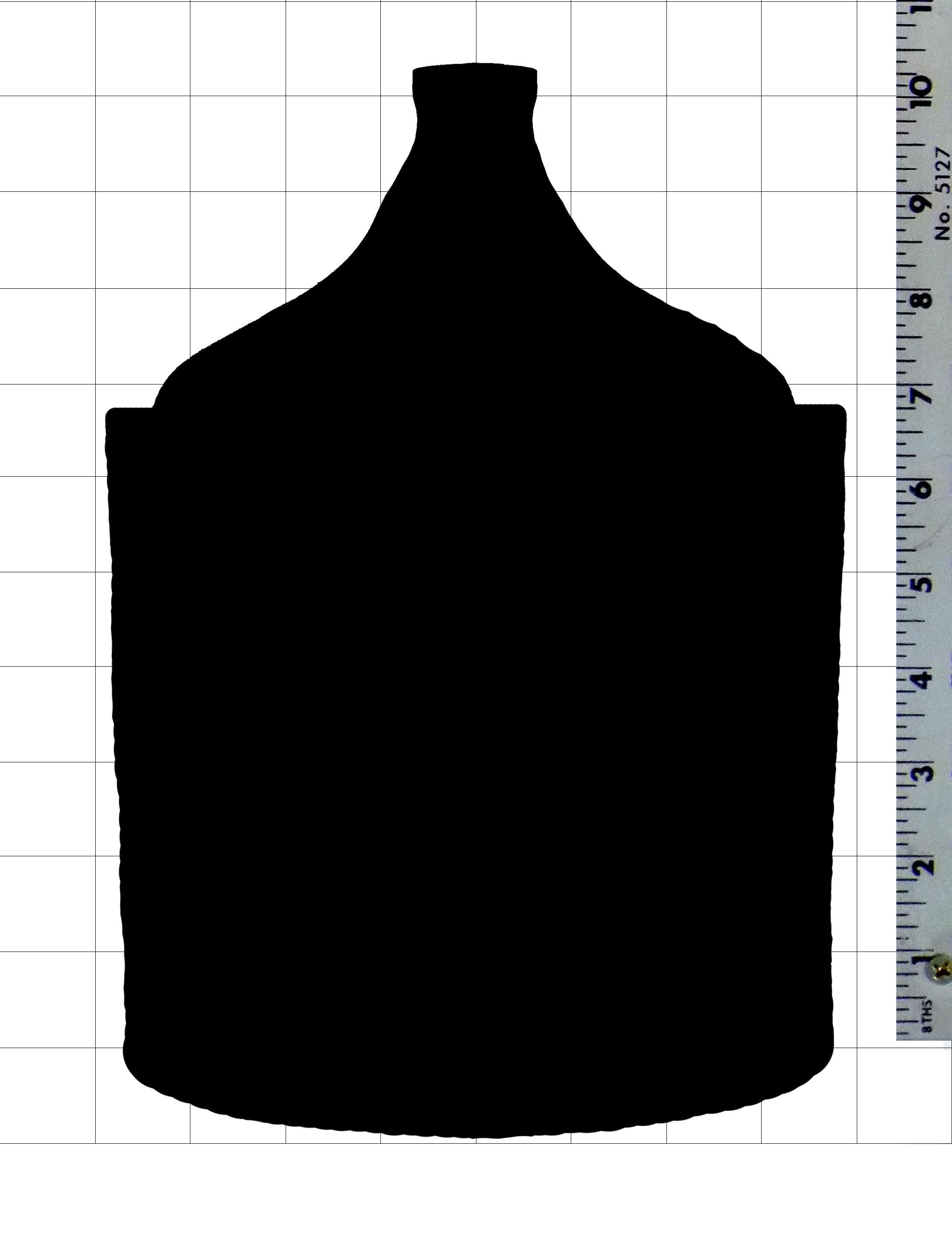

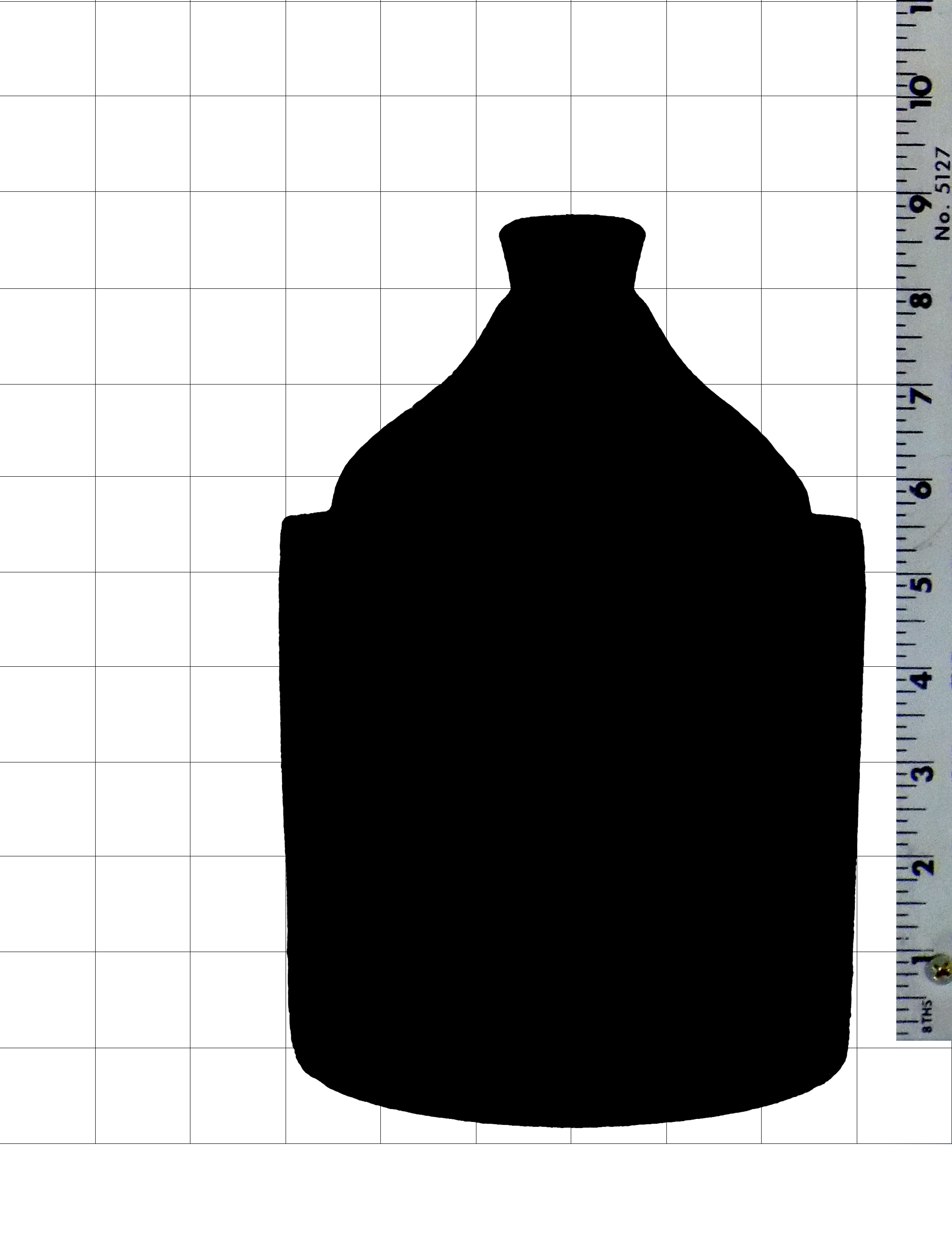

Upon sorting the jugs of the Leadville companies and the many other companies in the book (well over 100 examples), several jug styles became obvious, but with slight variations. At first, the variations did not seem important, but upon a closer look, the shapes did matter. Over the course of a pottery business, a style could vary and even vary slightly by each worker in the company. Therefore, the shapes of the jugs were carefully sifted and sorted grouping ones with the most exacting similar shape. The images in the book were not the best, as well as being small, so this took some time and reshuffling. Generally, two basic shapes emerged (and a few other shapes that were excluded and not relevant to the study). One shape is a geometric cylinder body with a relatively cone shaped spout on the top, and the other shape is a single formed piece known as a “bee sting”, basically looking much like a beehive. This bee sting jugs varied less, but the cylinder jugs had many subtle differences and was sorted into several groups. Another detail that varied was glaze. Some of the jugs had a brown glaze known as Albany slip on the inside and covering the spout, while other identical looking jugs did not have this glaze. The use or not of this brown glaze could have been a preference of the liquor company or it possibly could represent a progression of the preferred styles by the manufacturer at different times.

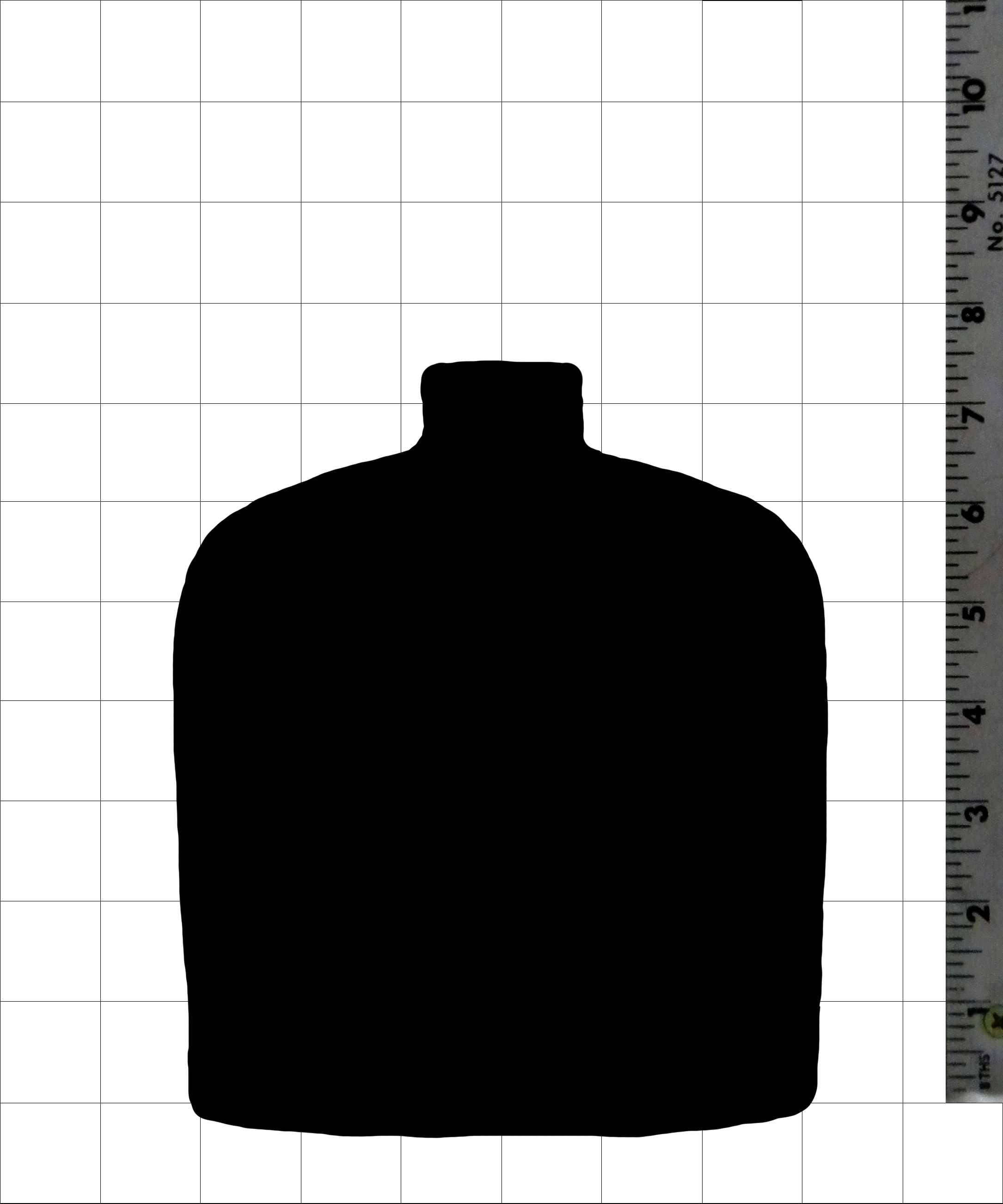

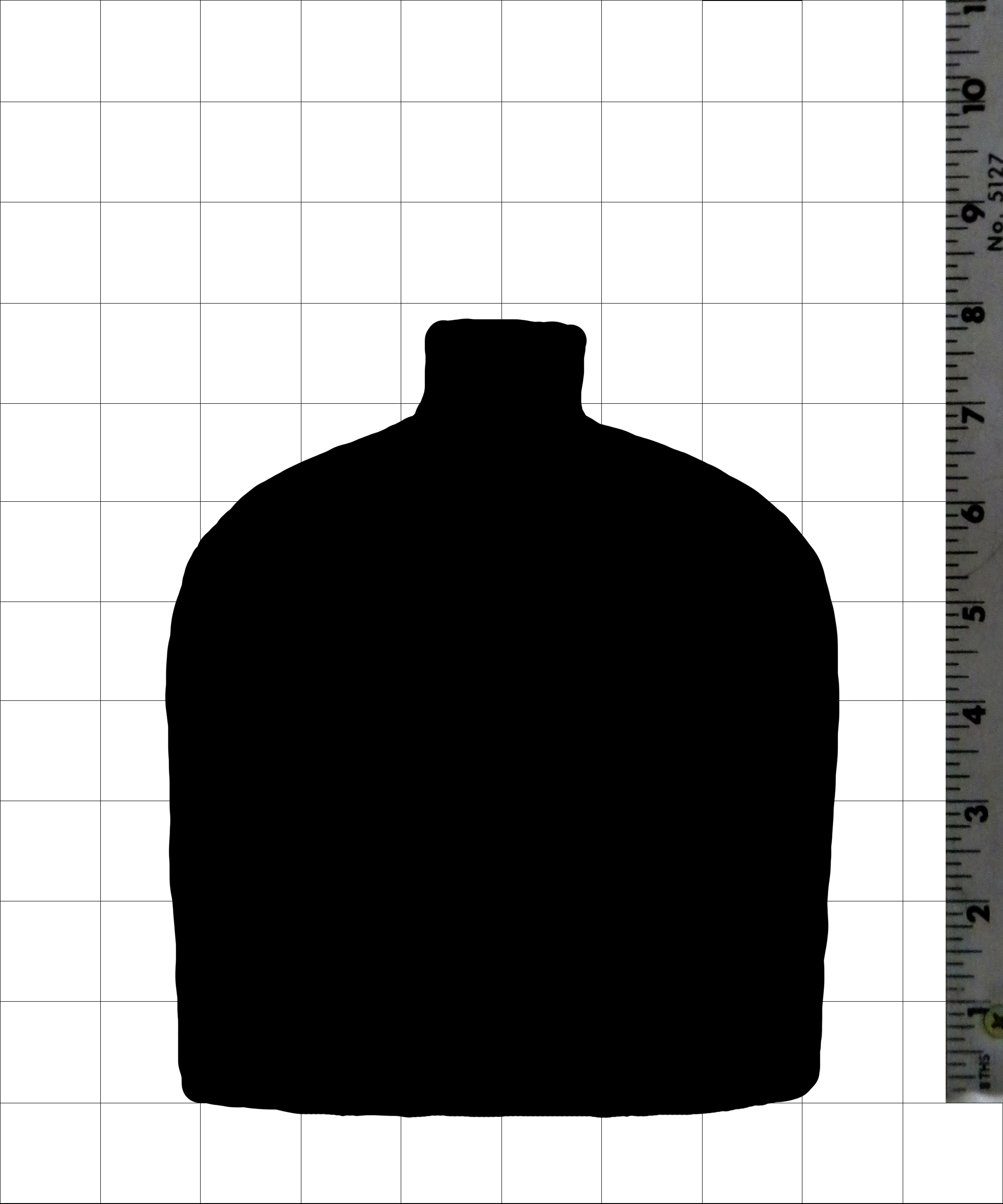

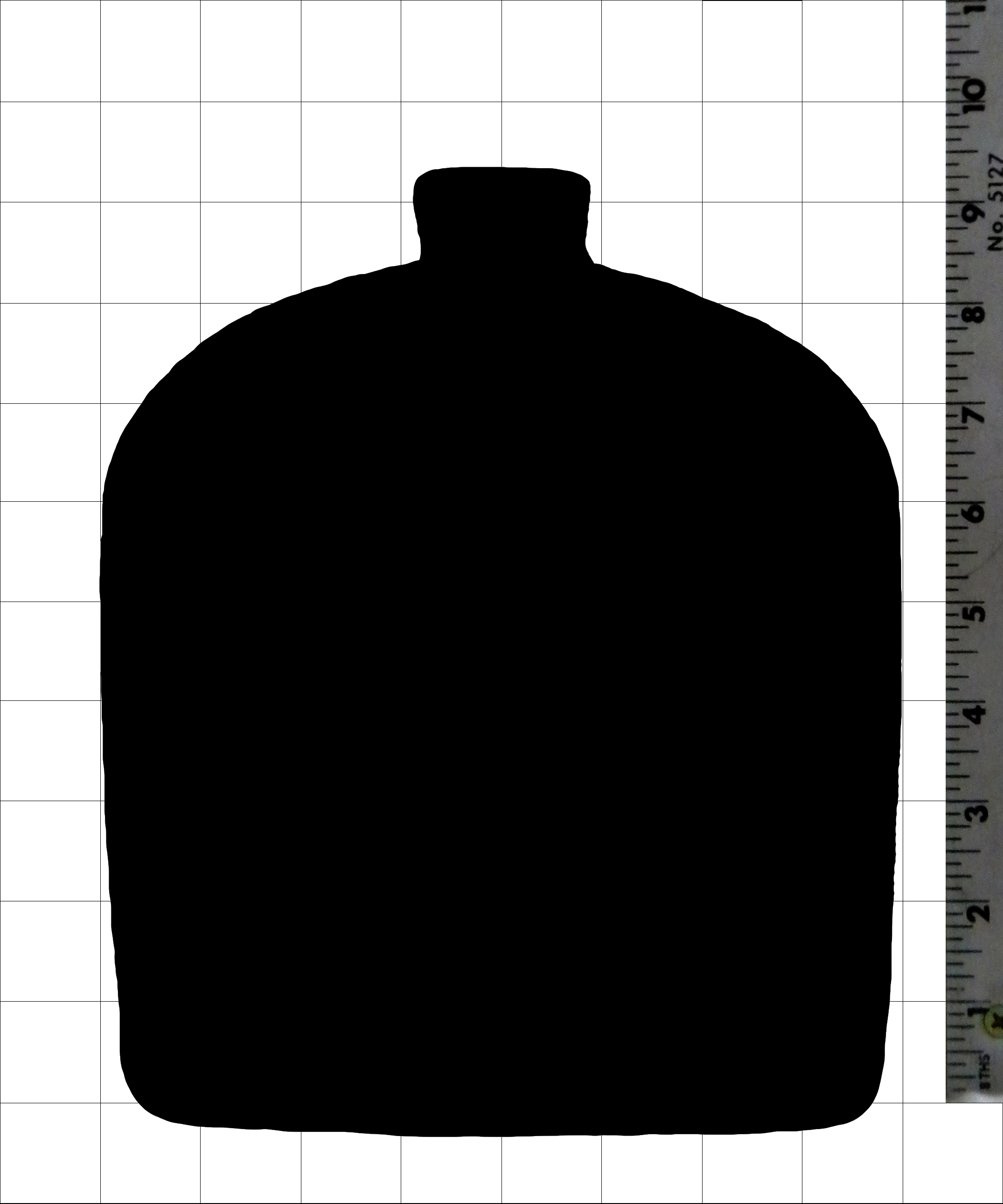

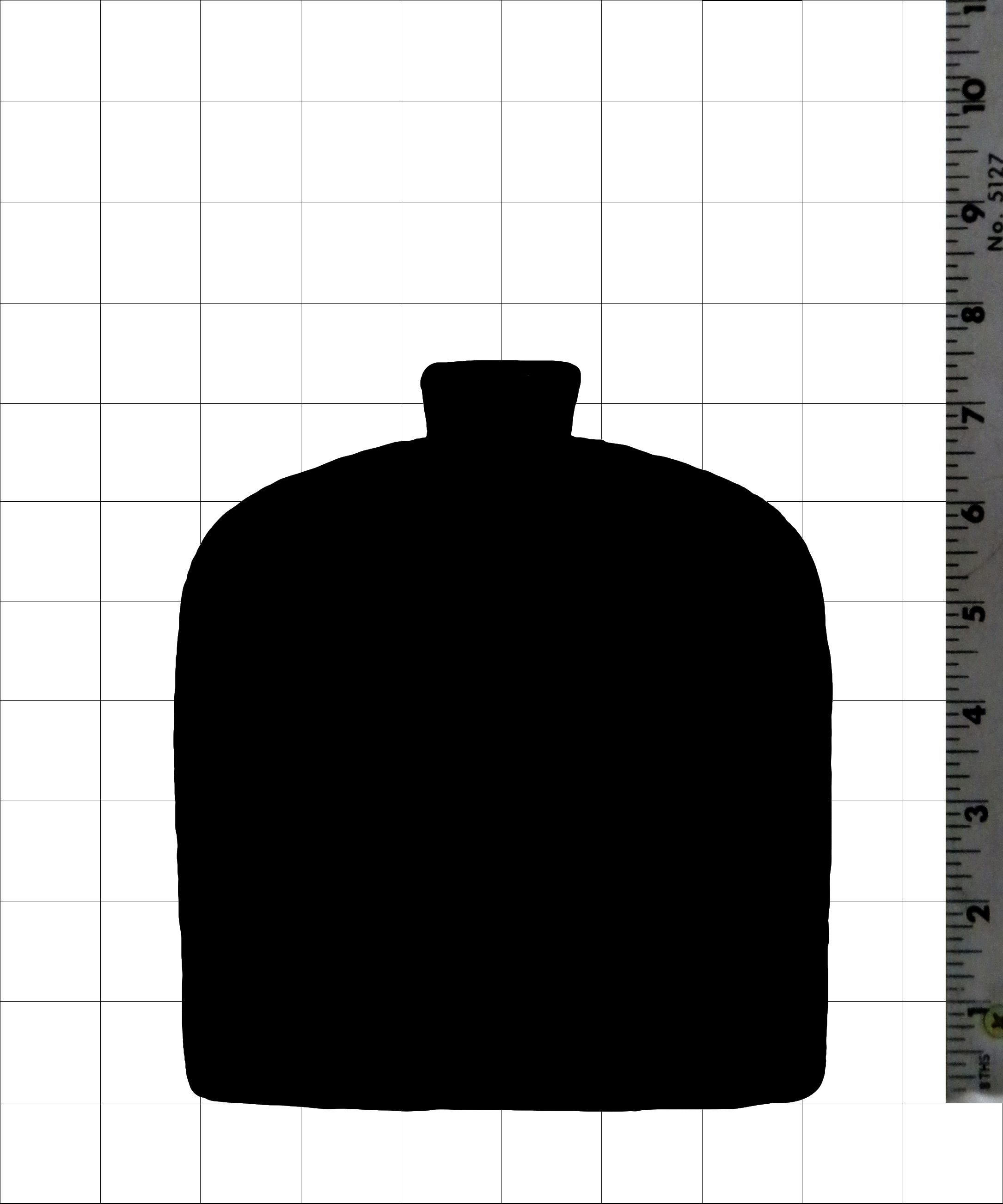

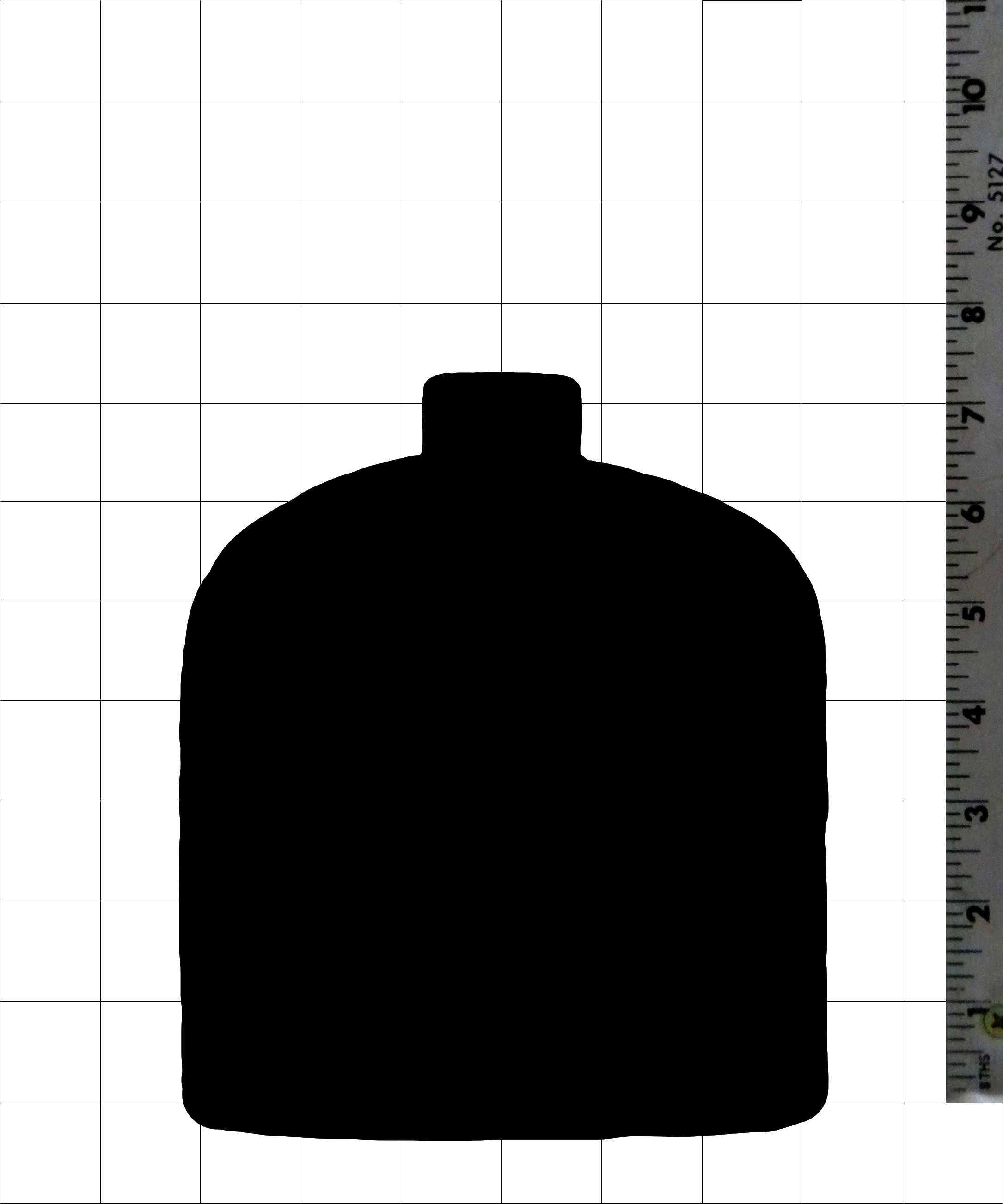

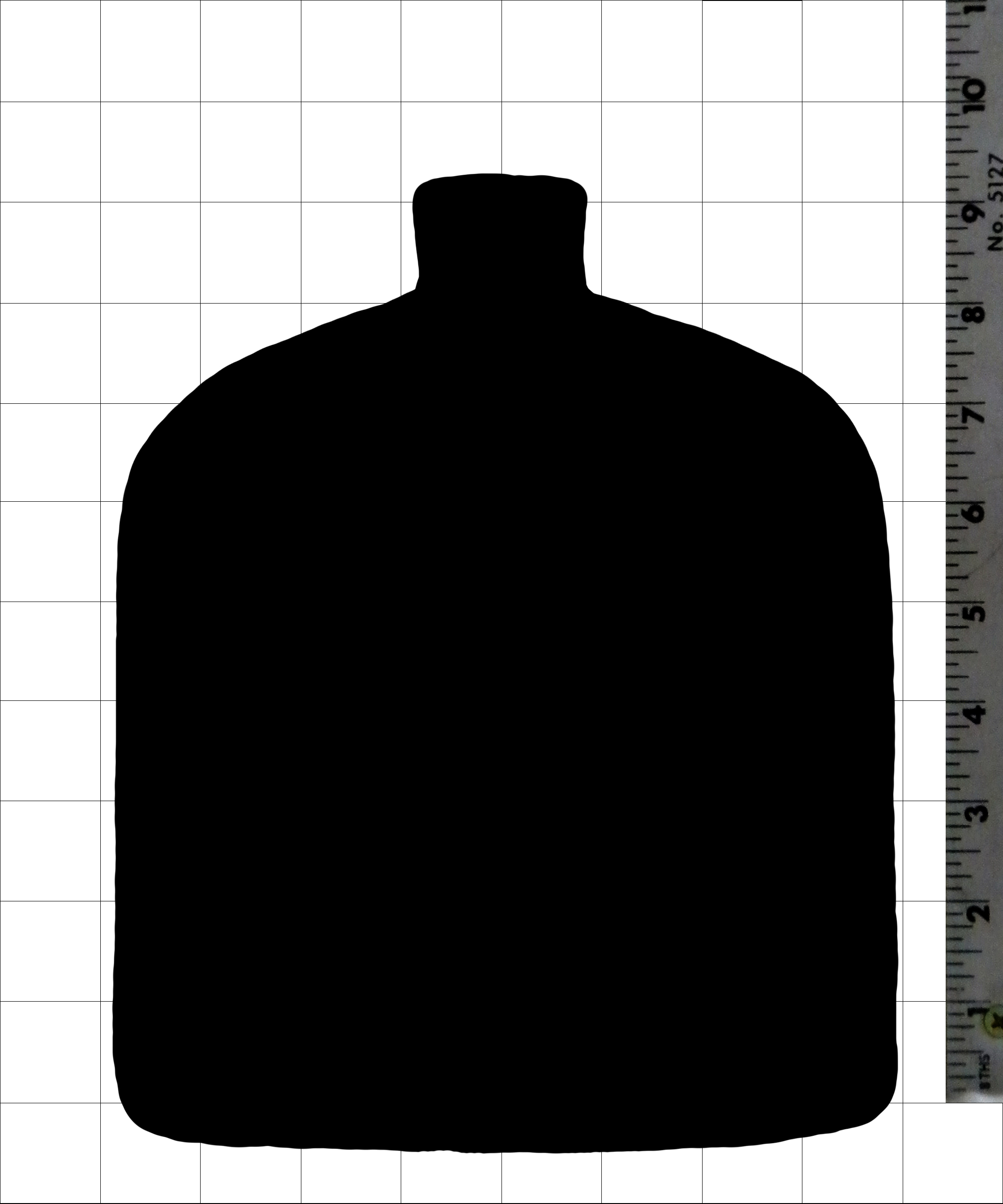

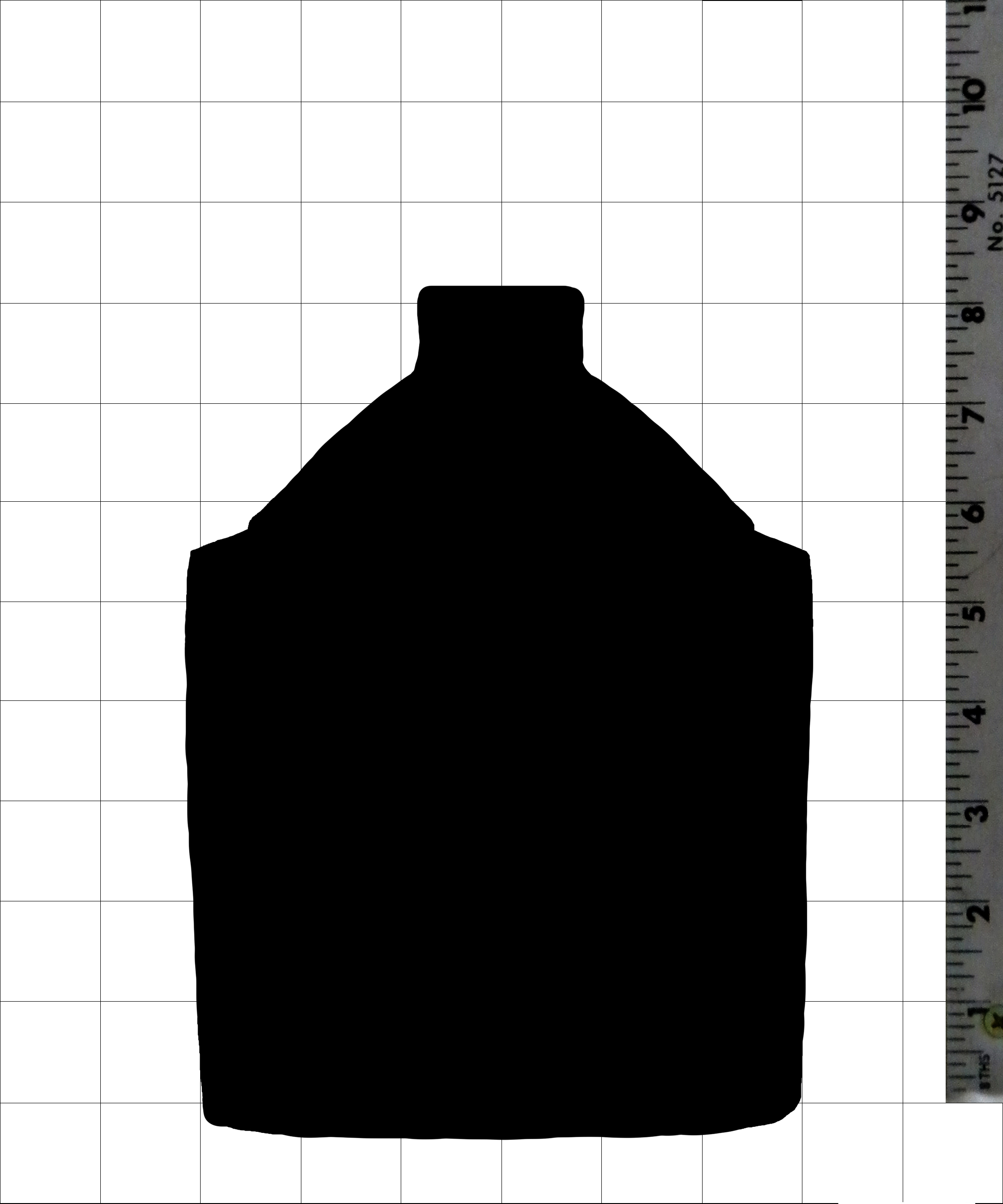

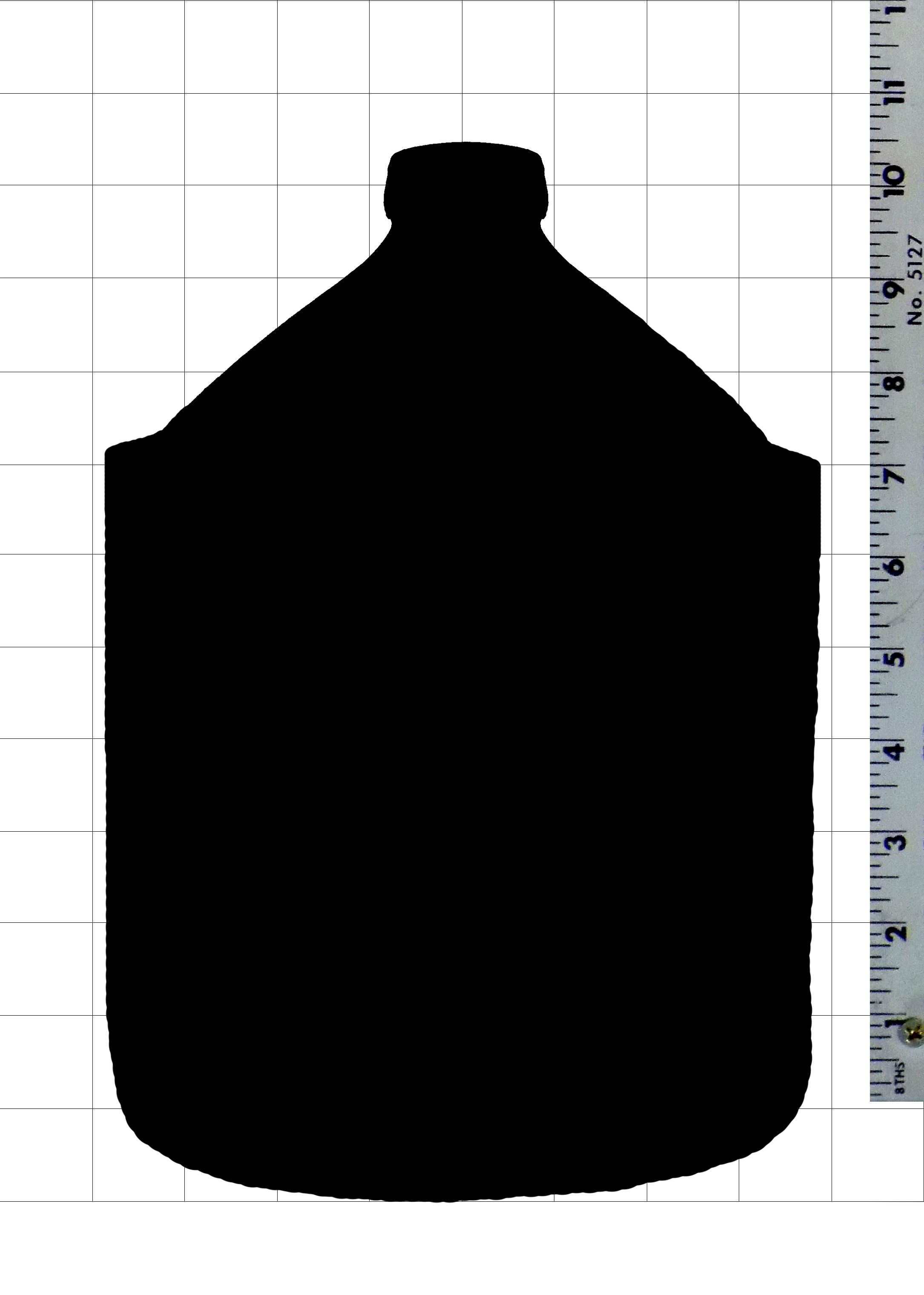

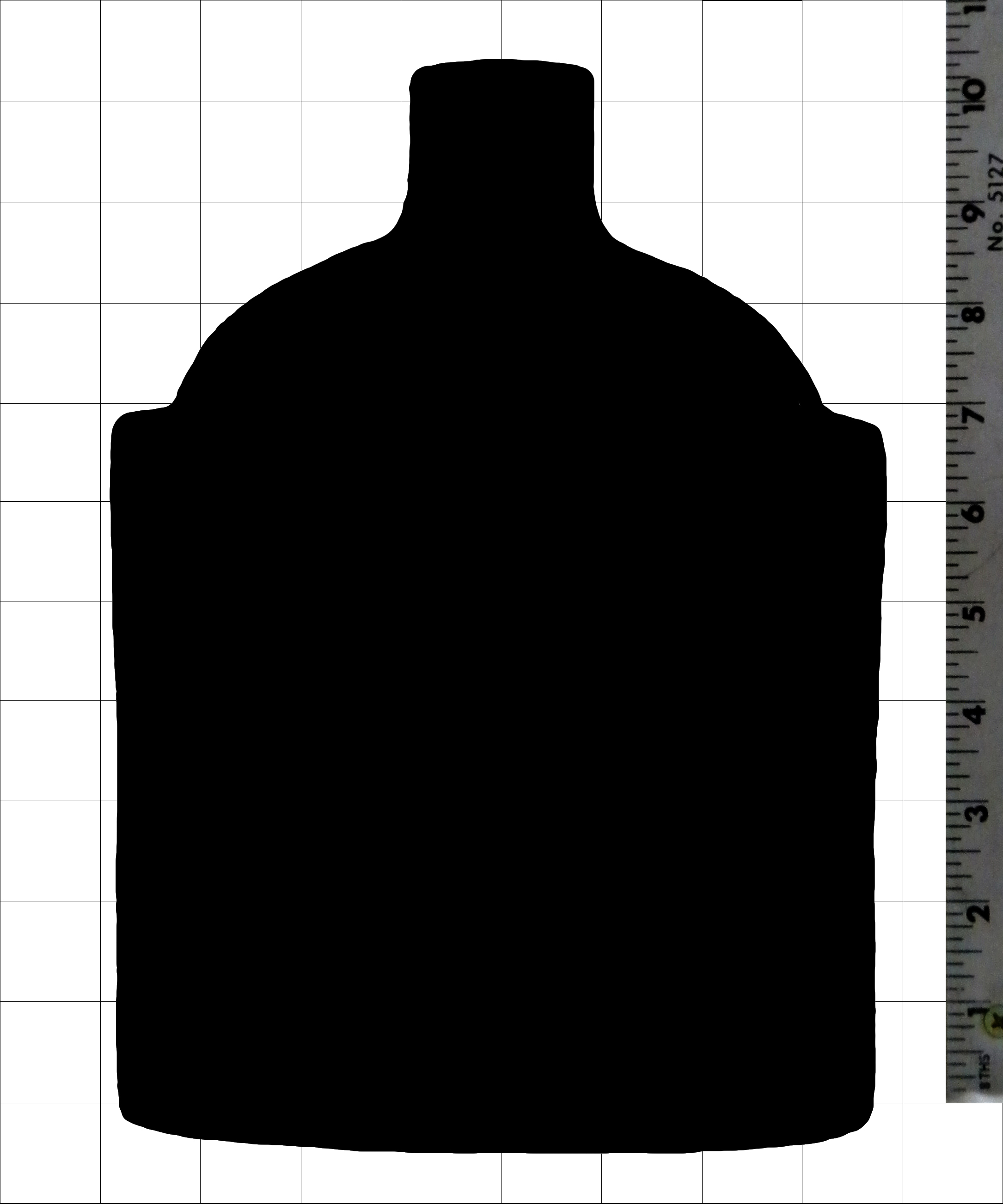

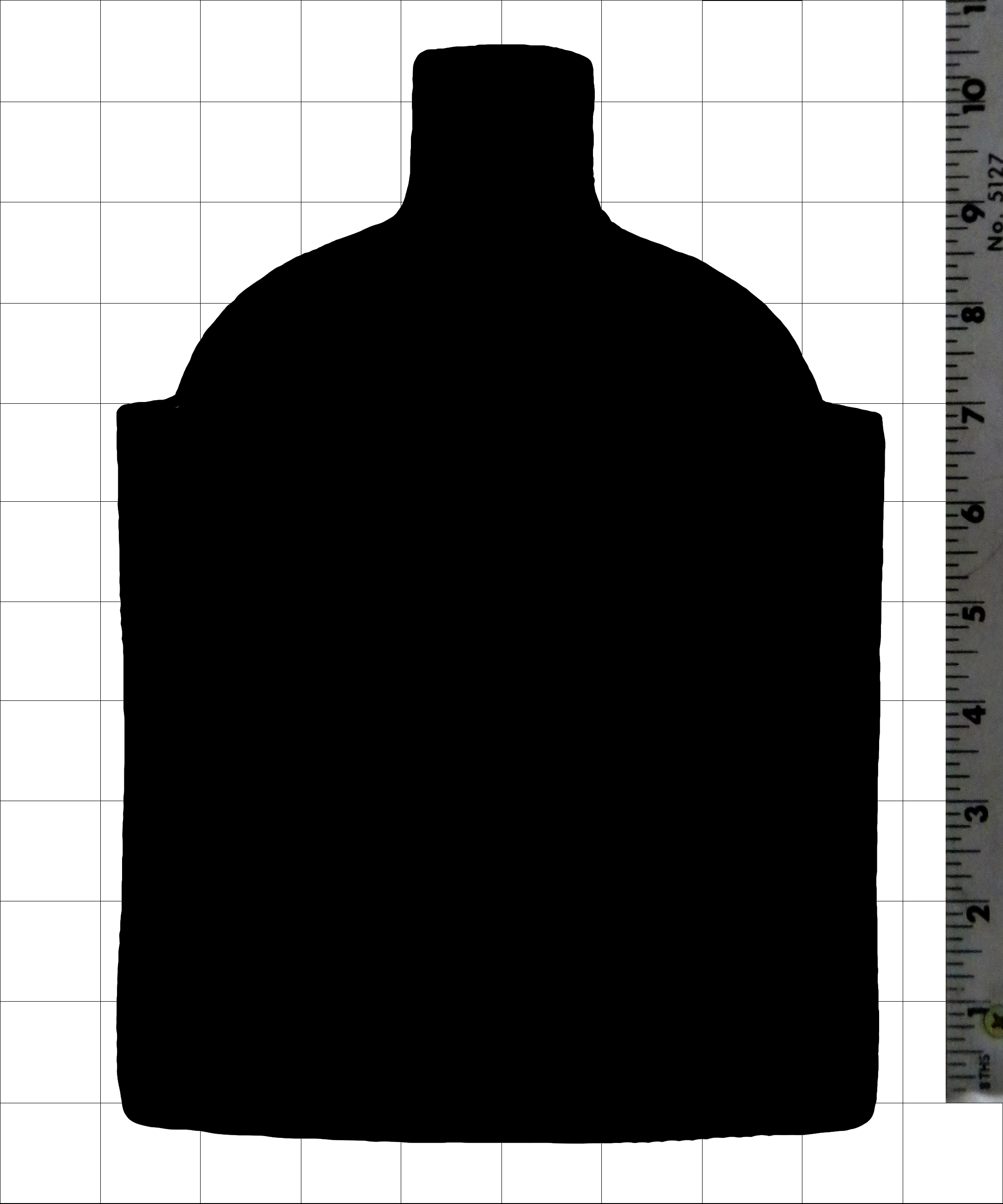

The flat silhouettes of the jugs in the museum collection were constructed in Adobe Photoshop directly from the taken photos. A ruler was next to the jugs in the correct position when the photos were taken in order to give accurate measurement references. While the position of the measurements in the silhouettes might seem off, it is already adjusted for the camera distortion. For most of the images, the camera was positioned just below the spout. For some of the photos, the camera was positioned slightly above the jug, making the rounded base seem more distorted. Also, the handles of the jugs were not included in the silhouettes in order to focus attention on the overall shape of the wheel thrown fabrication. All effort was made to trace the edges is closely as possible, but with a slight degree of error. The jugs themselves were not totally smooth and straight, and the silhouettes do highlight the flaws in the construction as well as the distortion of the photos.

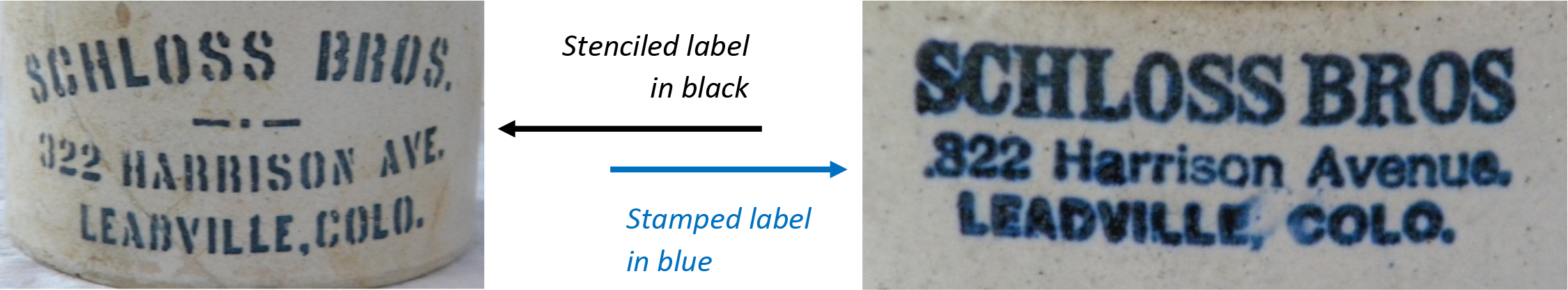

The most noticeable difference among the jugs of this shape have more to do with the labeling rather than the shape. Some of the jugs have large stencil type lettering that would be painted on, while others have cleaner and smaller lettering suggesting a stamping application (see Appendix H for more about jug labeling). A few examples had glaze over the entire body while some only at the top and others having no brown glaze at all. Of the Leadville jugs of the bee sting shape, they all had glaze at the top.

These group of five silhouettes show jugs that are wider in the middle near the top and narrows slightly down to the base.

The three jugs below are larger jugs of the ones to the right that are also wider near the top narrowing down to the base.

This next grouping shows the same style of jug in different sizes but that the sides are mostly perpendicular to the base staying relatively at the same diameter.

To better understand the cylinder jugs, they had to be meticulously sorted as best as possible. Two specific differences were noted. Some jugs had a lip or rim at the top of the spout while others were smooth not having any lipped articulation at all. Another difference of note is the profile of the neck. The main shapes were cone, dome, and S-curve. Some of the jugs had an elongated neck while others barely had a neck at all. See Appendix G for silhouette profiles of the jugs in the Temple Israel collection.

This group has a neck style that most closely resembles a cone, even though they do have a very slight convex curve.

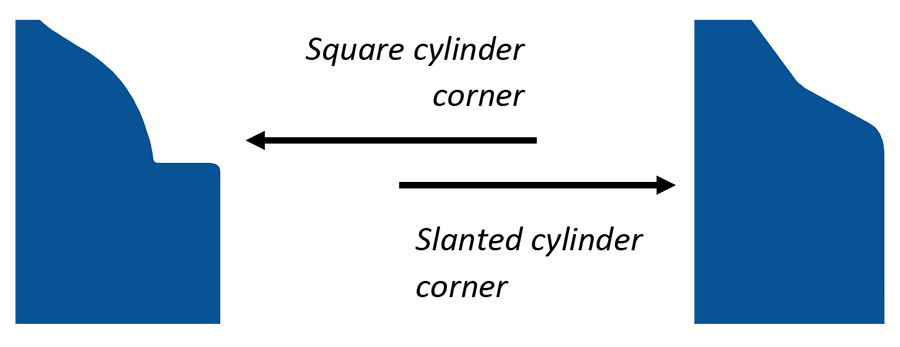

This group has a neck style that is similar to the last group in resembling a cone. However, these jugs seem a bit sloppier, but also they have a more distinct slant at the transition of the cylinder to the neck (see diagrams below).

The shape of the neck of this group is distinctly convex, domed shaped, from a square cornered cylinder. The spout is distinct and rises higher than with the other jugs.

This group shows the same cylinder base as most of the others, but the neck has a distinctive S shape with a relatively straight sided spout. The neck almost looks slumped, but is actually formed to be low.

Almost the same as the previous shape, the neck is longer overall, about 20% taller. Also, the spout slopes right into the neck with no real distinction of the spout from the neck.

This group is much like the last group, but has a distinct spout that is flared at the top. Some of the Bee Sting jugs also have the same type of flared spout (shown to the right).

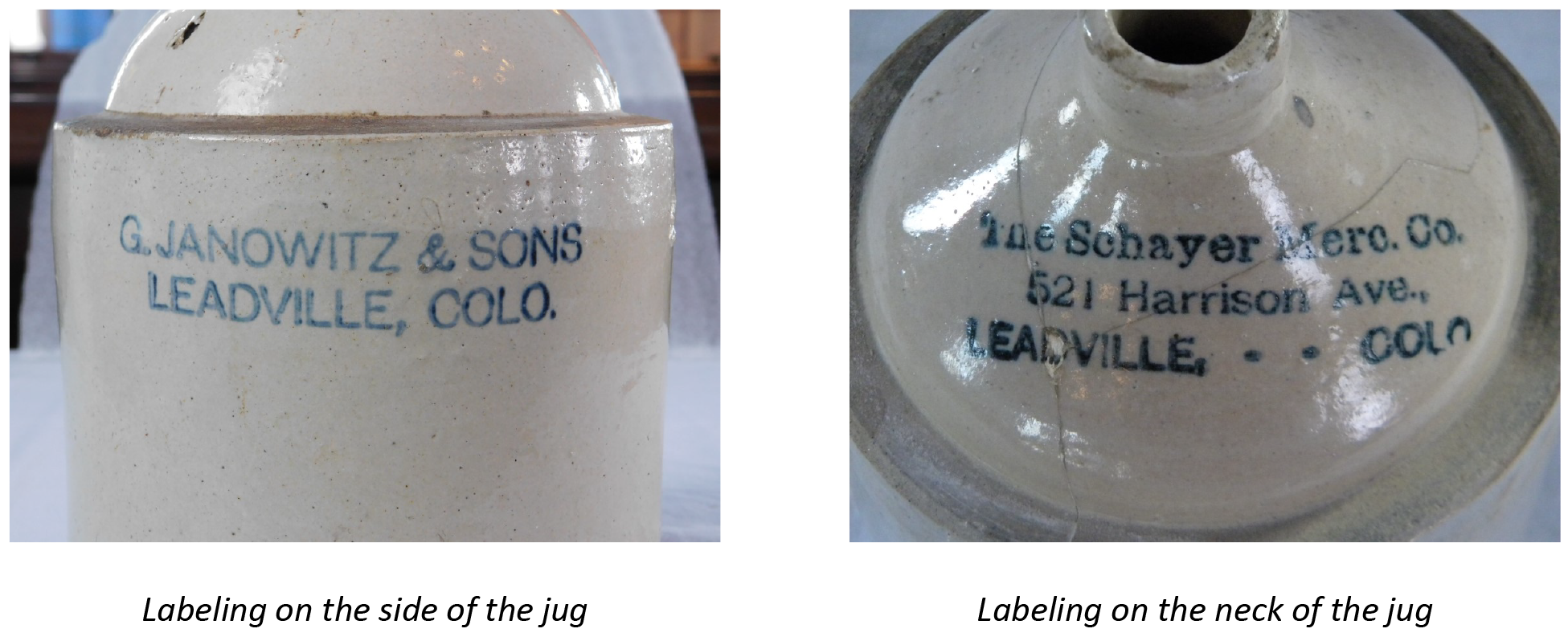

Just as important as the shape of the jug is the labeling on the jug. Labeling identifies the jug with a specific company that purchased it from the manufacturer for filling and selling. Several patterns became obvious when comparing the different labels on the jugs in the museum’s collection. First, two main application methods were used, stenciling and stamping. Second, the color of the label was either blue or black/gray with one unusual example in brown.

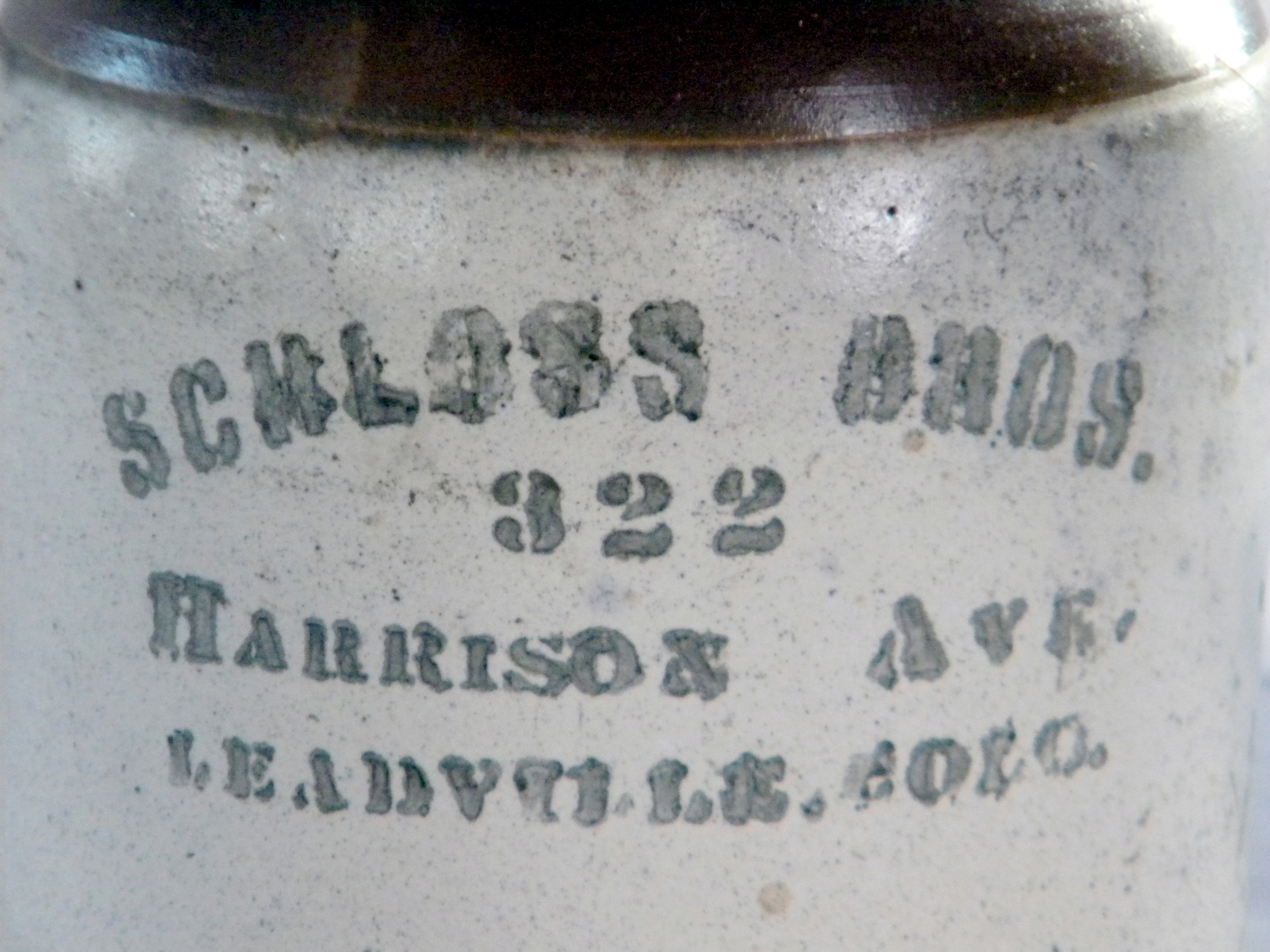

One of the most obvious differences in labeling is stenciling. Stenciling by nature is usually larger and has a distinctive characteristic of cut letters. After stencils were made, paint or stain was pushed through the openings in the stencil onto the jug. For the museum collection jugs, stenciled labeling was only found on the bee sting shape and specifically for Schloss Brothers. The one exception is a [S.] F. Ballin & Company clay bottle. (It is unknown why the full name was not put on the clay bottle, S. F. Ballin & Company.) However, stenciled lettering was used on other shaped jugs for other liquor companies in Colorado.

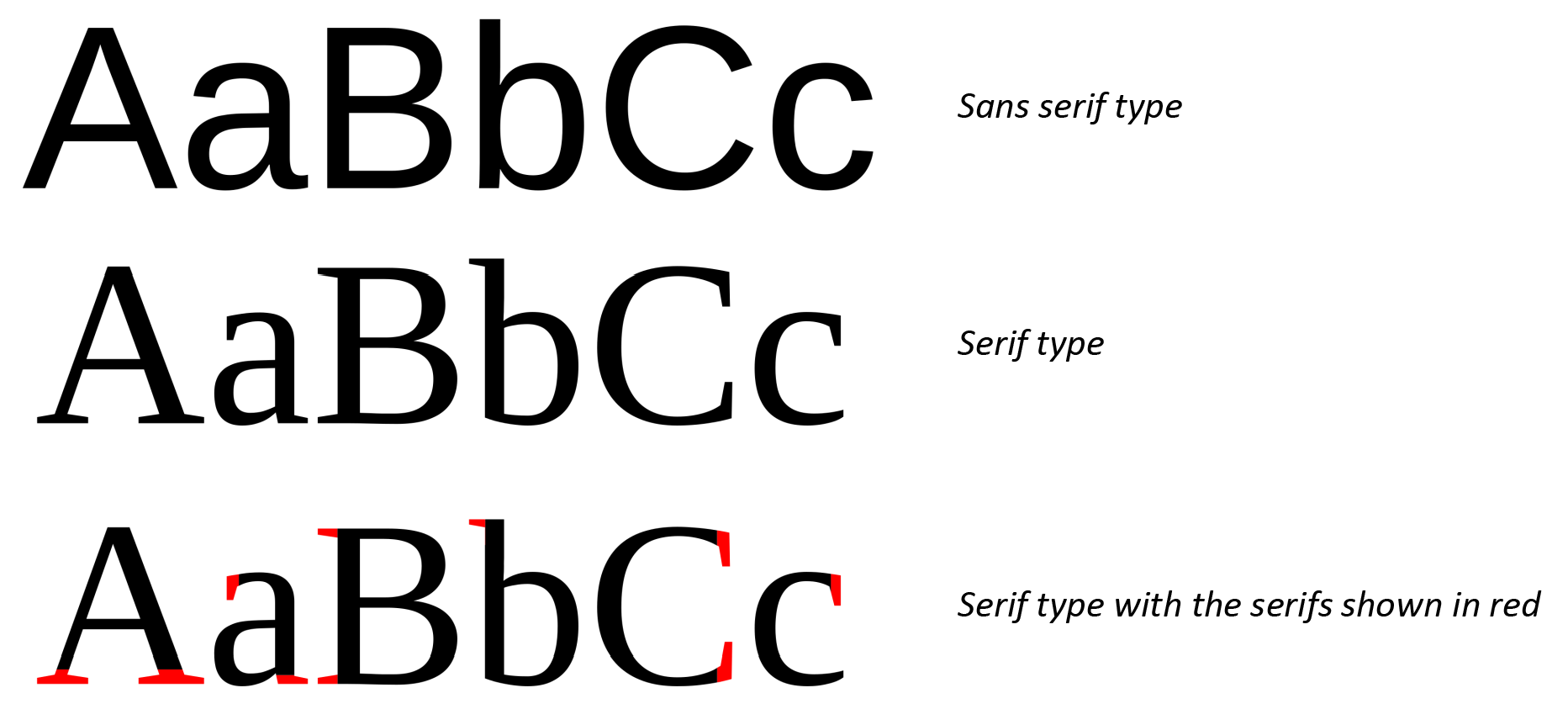

Labeling that was stamped allowed for a smaller and more compact label that typically appeared cleaner and easier to read. Nearly all of the stamped examples are in blue. Stamping is much like a rubber stamp in that raised sections are inked then pressed onto the jug. While the cut letters of stenciled labeling is a style all to its own, stamped labeling can be much more varied and can access typeface styles popular of the day, not unlike how newspapers used different type for the newspaper header. Therefore, type has two main forms, serif and sans serif (sans being French for without, so without serifs). Serif typefaces are letters that have accentuated points on the letters. Therefore, a sans serif typeface does not have the serifs and is often a visually cleaner, simpler looking type.

With the group below, all the same company, the labeling shows a full width sans serif font, which makes each letter nearly as wide as it is high, giving it an almost square appearance. These jugs are the only example of this typeface in the museum collection.

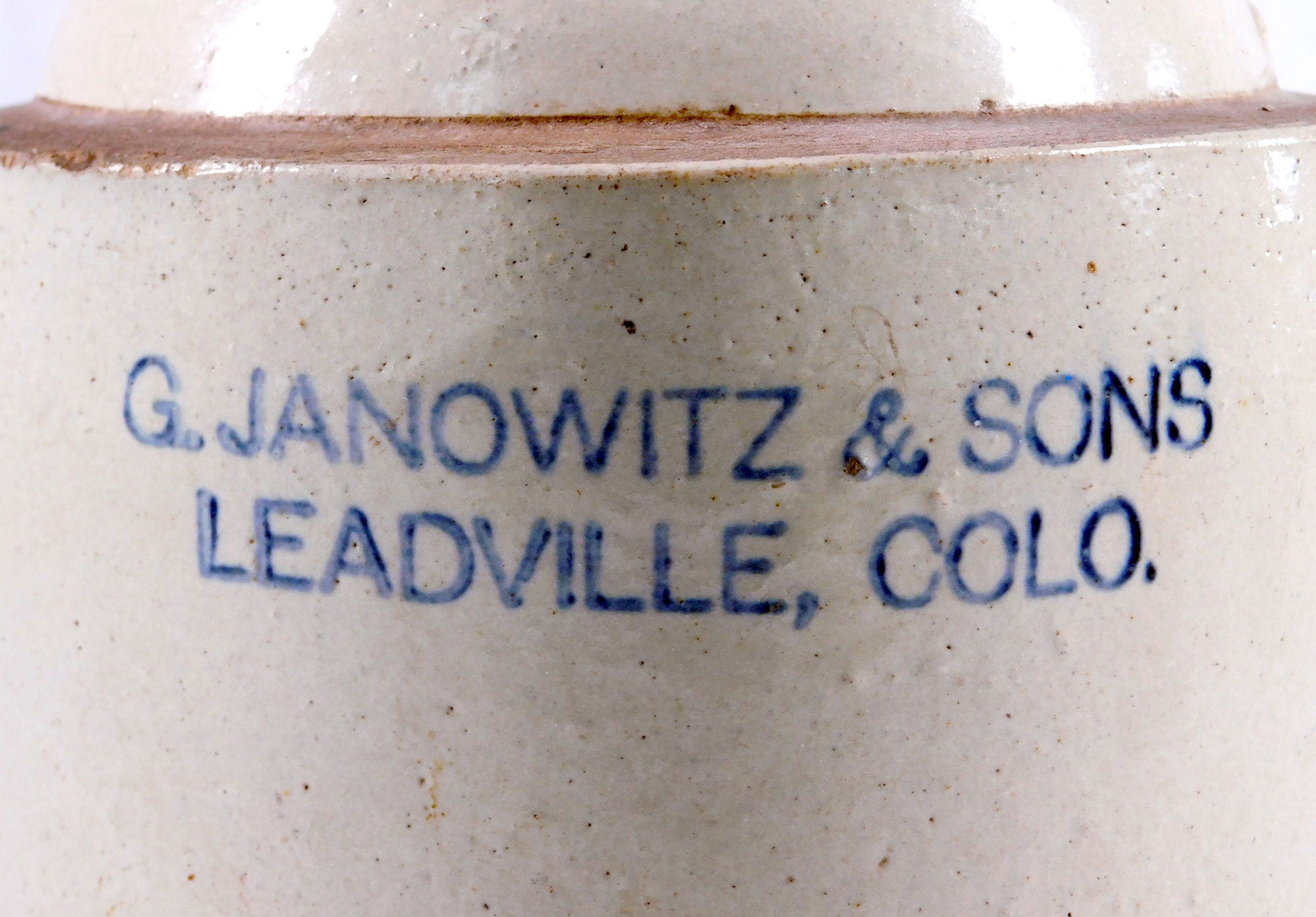

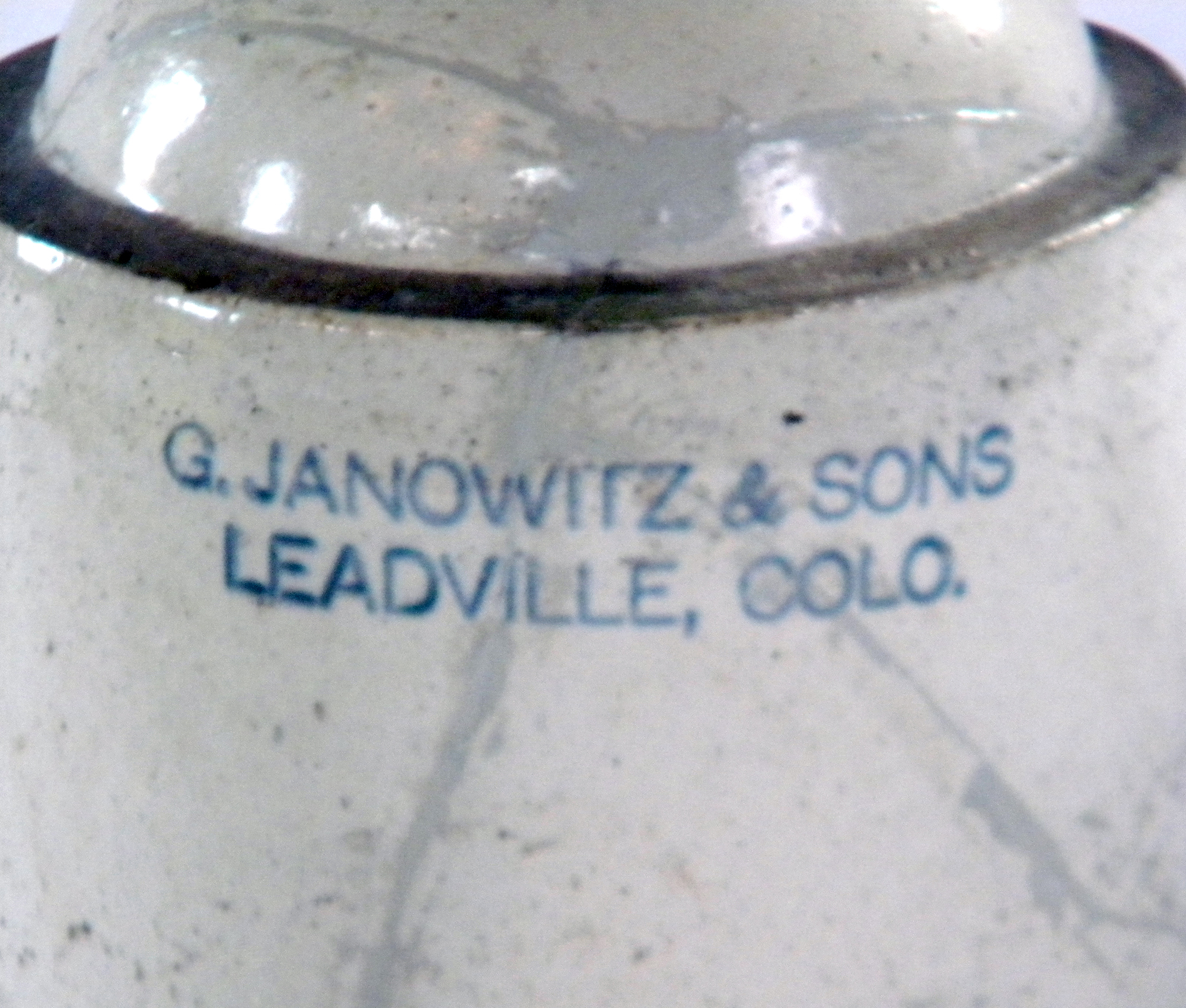

The rest of the jugs in the collection have serif type labeling. However, the arrangement of the name, address, and location information varied with each company and probably with each manufacturer.

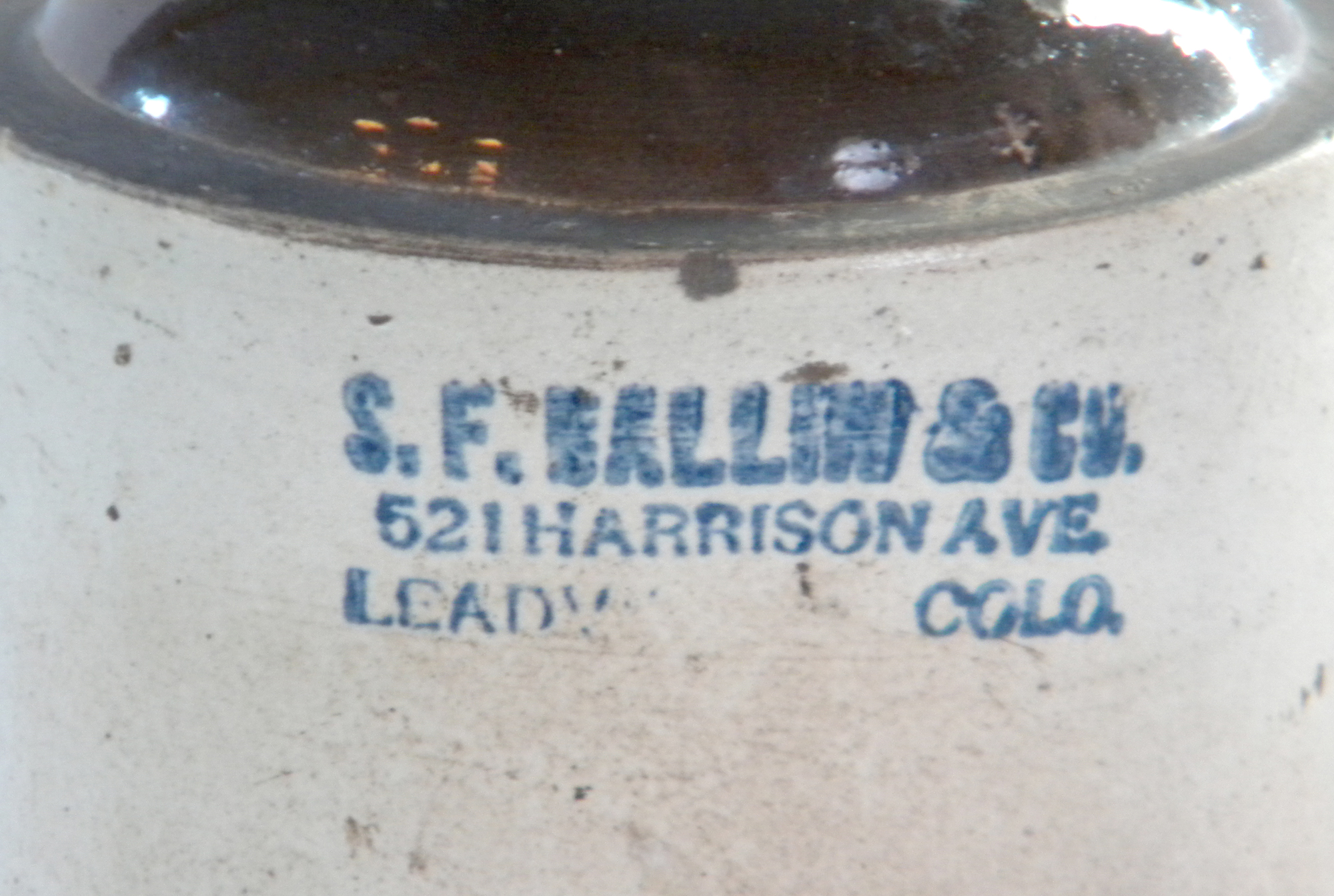

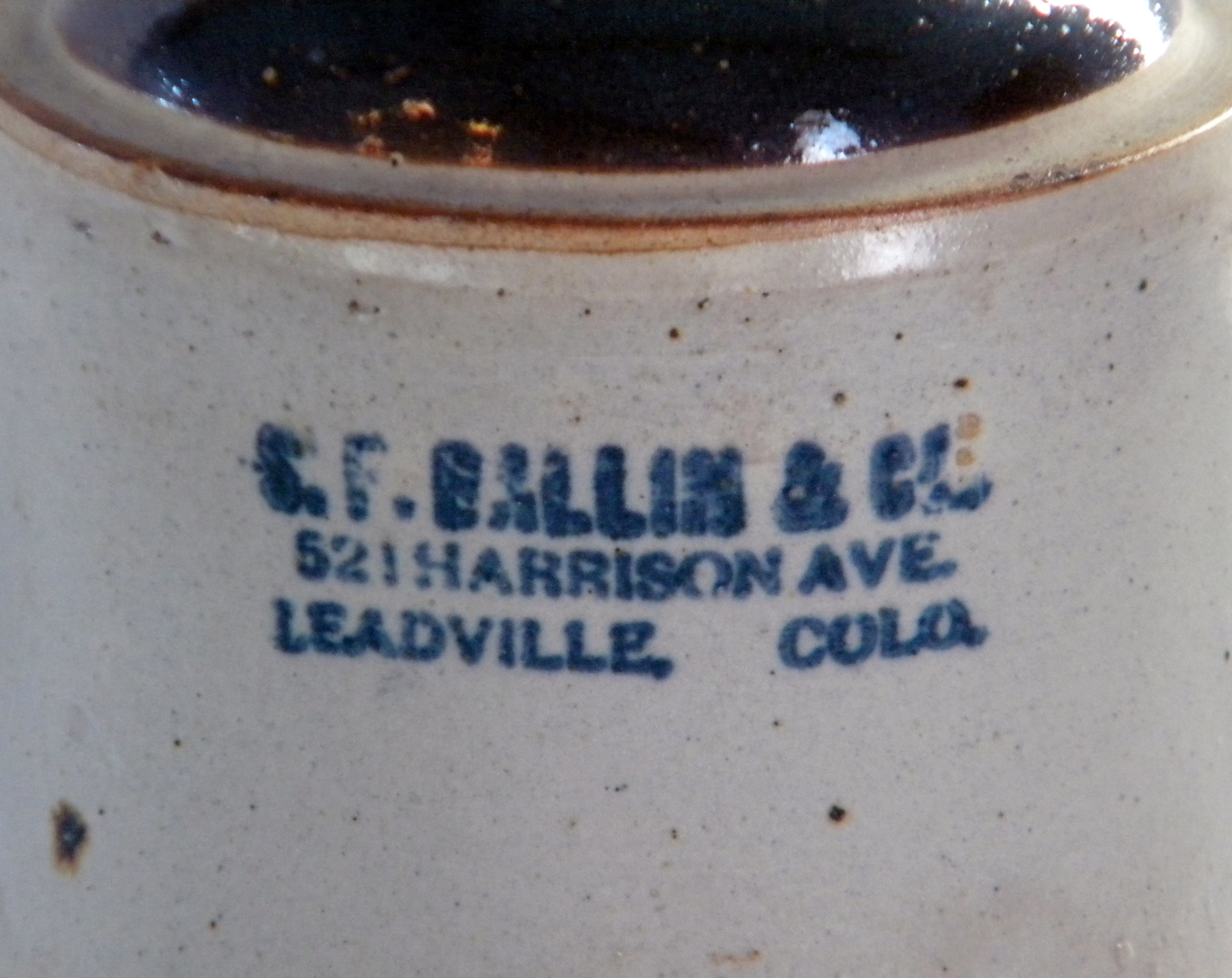

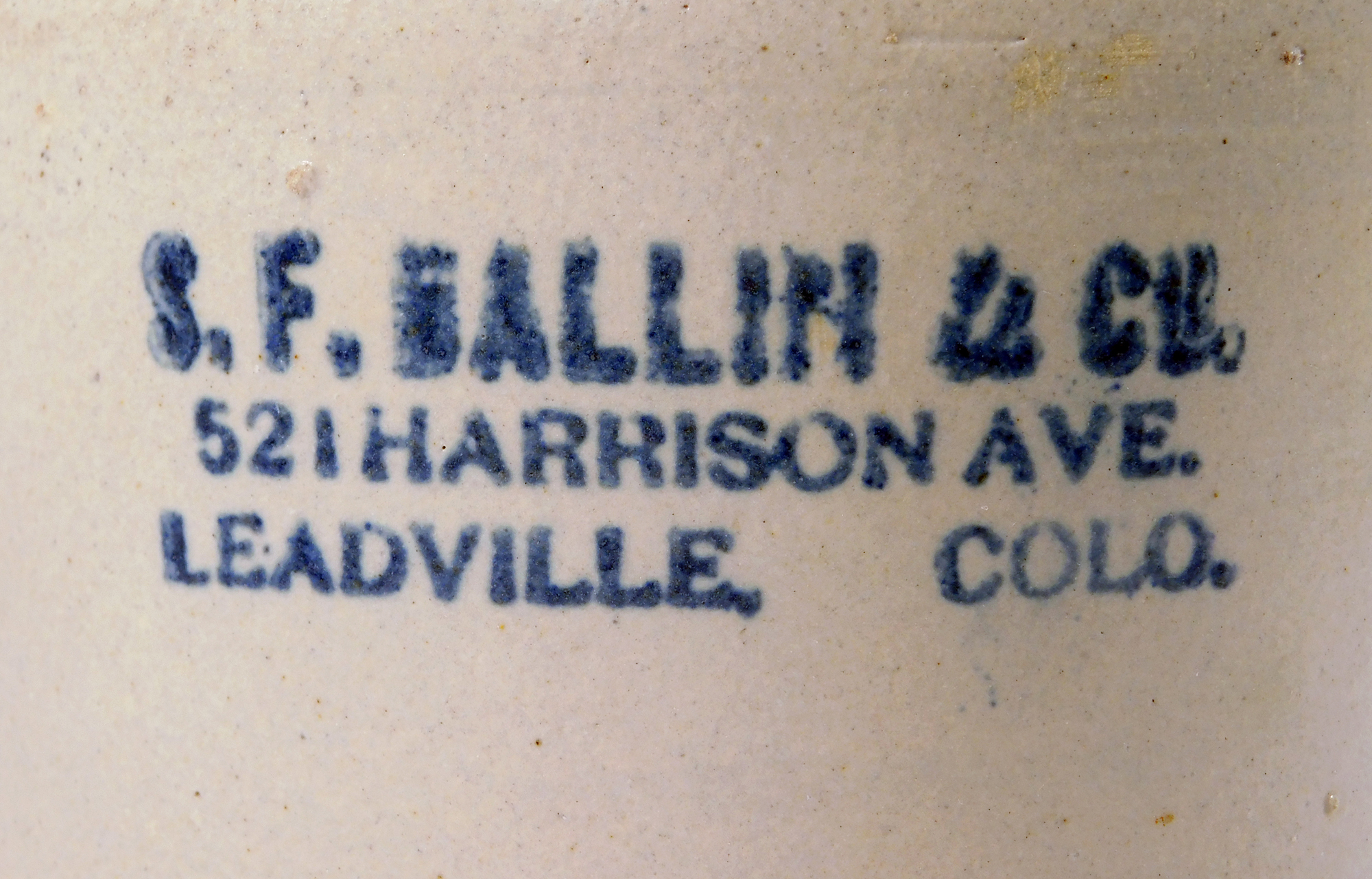

With the bleeding of the stamp, it is a little difficult to tell, but these Ballin jugs appear to mix the type by having a sans serif company name, but serif text for the other two lines.

The group below is the longest, fanciest, and latest of the jug labeling. There appears to be three or four typefaces of mixed kinds on six lines. This company dates to 1910-1912 and shows a typeface style appearing much like Art Nouveau, particularly with the top line.

One particular company is a little difficult to pin down the jug manufacturers, Schloss Brothers. Unlike other companies that moved often or went by varied names, Schloss Brothers stayed consistent in name and location for at least a decade or did not use the full company name on the jugs. The difficulty too is that the company had multiple styles of jugs but had what appears to be identical labeling. This makes determining if the jugs were used sequentially or simultaneously difficult to determine.

These particular two jugs are a little different in that the typefaces are a little different, but also that the building number is on a separate line from the street name. The only other occurrence of this is with the cut letters of the stenciled jugs.

The general observed times of need of liquor jugs appeared to greatly increase in the 1890s until Colorado prohibition started in 1916, which halted the need for stoneware liquor jugs, devastating both potteries and liquor companies. The antialcohol movement was gaining momentum in the United States in the late 1800s. First was effort to halt liquor sales on Sundays, known as the Lord’s day, and would eventually lead to the national prohibition starting in 1920 and lasting until the end of 1933, the middle of the Great Depression, when the law was repealed. Apparently, Leadville had an edict where after April 15 of 1895, saloons and liquor sales had to shut down by midnight on Sundays for a full 24 hours. Enforcement would apparently be strict with imprisonment as a fine for breaking the law. Another article referenced the edict by suggesting stoneware crock salesmen to come to Leadville to supply liquor companies with a means for people to purchase quantities of liquor ahead of time for Sunday consumption. This seems to be the point where larger quantities of liquor sold in several jug sizes skyrocketed.

While determining the exact date a clay jug was made is nearly impossible to determine, using the information obtained as explained in this writing certainly narrows the date range. In most cases, the dates are limited to a few years, with some longer and some shorter. In addition, determining the maker of each jugs without any manufacturer markings is also difficult to determine. However, using the date ranges and the known dates of when the potteries existed can give plausible conclusions. While not absolute, we can draw conclusions to determine the manufactures and dates until more information can come available to either prove or disprove the plausible results.

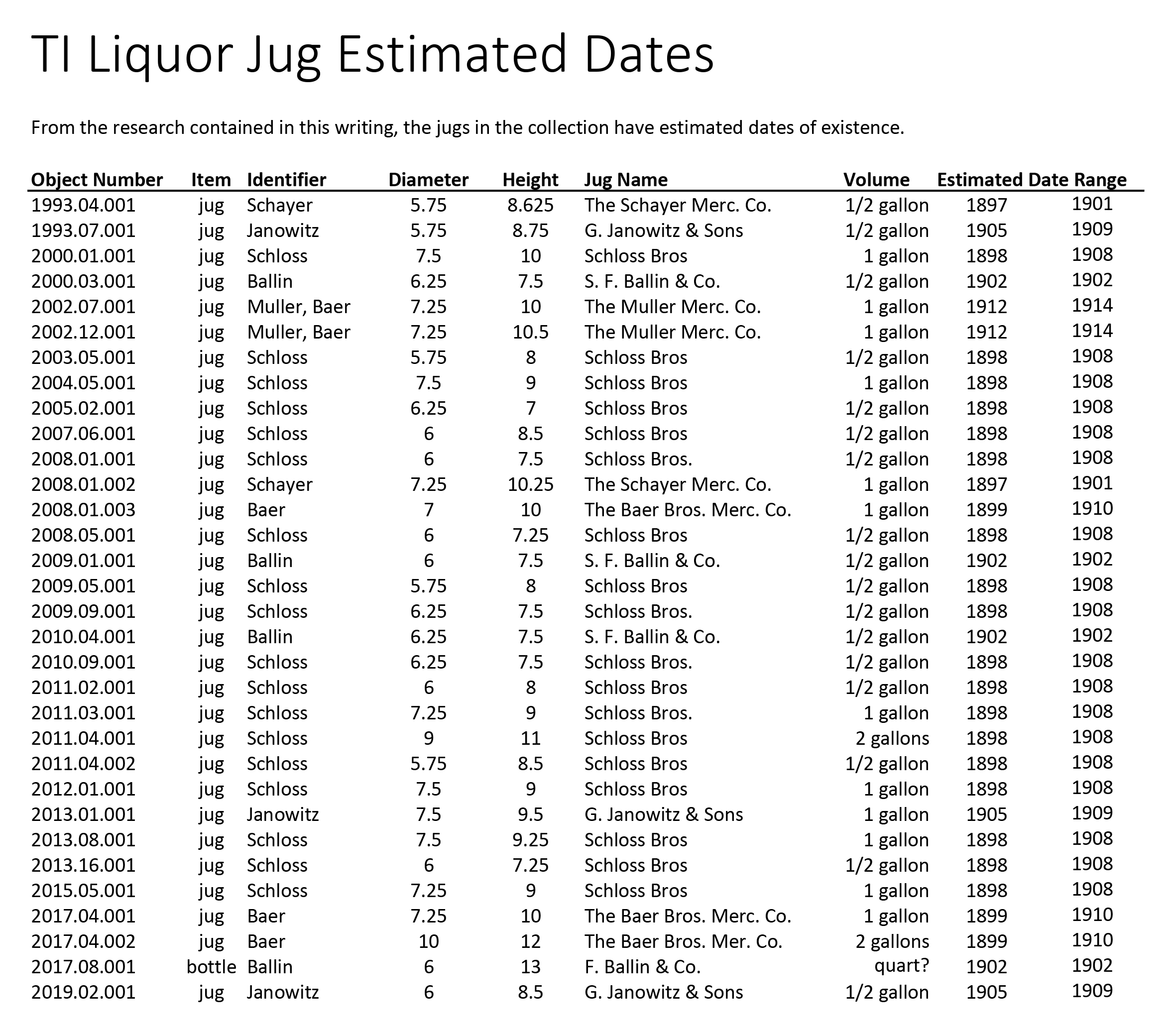

This table shows the plausible date conclusions of the Temple Israel museum jugs.

1 https://erstwhileblog.com/2019/02/27/colorado-prohibition-movement

2 David K. Clint & Company [compiler], Colorado Historical Bottles & Etc., 1859-1915. Antique Bottle Collectors of Colorado.

3 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prohibition_in_the_United_States

4 The Herald Democrat. Friday, May 24, 1895. Page 6. (See appendix E for the article)

This is a compiled resource of the sources used in this research.

David K. Clint & Company [compiler], Colorado Historical Bottles & Etc., 1859-1915. Antique Bottle Collectors of Colorado.

Temple Israel Museum artifact collection database

Soil Survey of Golden Area, Colorado. United States Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service. 1980.

Clay mining with George H. Golightly, part I. https://www.goldenhistory.org/clay-mining-with-george-h-golightly-part-i. Accessed January 2020.

Dry Times in the Highest State: Colorado’s Prohibition Movement. https://erstwhileblog.com/2019/02/27/colorado-prohibition-movement. Accessed January 2020.

Prohibition in the United States. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prohibition_in_the_United_States. Accessed January 2020.

The Herald Democrat. Friday Morning, May 24, 1895. Page 6.

The Avalanche Echo. Thursday, April 11, 1895. Page 2.

Leadville City Directories

Clark, WM, Root WA and Anderson, HC. Clark, Root and Co’s First Annual City Directory of Leadville and Business Directory of Carbonateville, Kokomo and Malta for 1879. Denver, CO: Daily Times Steam Printing House And Book Manufactory. 1879.

Corbett, TB, Hoye, WC and Ballenger, JH. Corbet, Hoye and Co’s First Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City Of Leadville for 1880. Leadville, CO: Democrat Printing Company. 1880.

Corbett, TB and Ballenger, JH. Corbet, and Ballenger’s Second Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City Of Leadville for 1881. Leadville, CO: Corbet and Ballenger Publishers. 1881.

Corbett, TB and Ballenger, JH. Corbet, and Ballenger’s Third Annual City Directory: Containing A Complete List Of The Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms Etc. In The City Of Leadville For 1882. Leadville, CO: Corbet and Ballenger Publishers. 1882.

Corbett, TB and Ballenger, JH. Corbett, and Ballenger’s Fourth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City Of Leadville for 1883. Leadville, CO: Corbet and Ballenger Publishers. 1883.

Corbett, TB and Ballenger, JH. Corbet, and Ballenger’s Fifth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City Of Leadville For 1884. Leadville, CO: Corbet and Ballenger Publishers. 1884.

Corbett, TB and Ballenger, JH. Corbet, and Ballenger’s Sixth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City Of Leadville For 1885. Leadville, CO: Corbet and Ballenger Publishers. 1885.

Corbett, TB and Ballenger, JH. Corbet, and Ballenger’s Seventh Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City Of Leadville For 1886. Leadville, CO: Corbet and Ballenger Publishers. 1886.

Corbett, TB and Ballenger, JH. Corbet, and Ballenger’s Eighth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City Of Leadville For 1887. Leadville, CO: Corbet and Ballenger Publishers. 1887.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Ninth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1888. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1888.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Tenth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1889. Leadville, CO: Corbet and Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1889.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Eleventh Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1890. Leadville, CO: Corbet and Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1890.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Twelfth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1891. Leadville, CO: Corbet and Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1891.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. “Ballenger & Richard’s Thirteenth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1892”. Leadville, CO: Corbet and Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1892.

No directory made for Leadville in 1893.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Fifteenth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1894. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1894.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Sixteenth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1895. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1895.

No directory made for Leadville in 1896.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Eigteenth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1897. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1897.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Nineteenth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1898. Leadville, CO: Corbet and Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1898.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Twentieth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1899. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1899.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Twenty-First Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1900. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1900.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Twenty-Second Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1901. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1901.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Twenty-Third Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1902. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. Leadville, CO; USA. 1902.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Twenty-Fourth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1903. Corbet and Ballenger and Richards Publishers. Leadville, CO; USA. 1903.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Twenty-Fifth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1904. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1904.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Twenty-Sixth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1905. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1905.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Twenty-Seventh Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1906. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1906.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Twenty-Eighth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1907. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1907.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Twenty-Ninth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1908. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1908.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Thirtieth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1909. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1909.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Thrity-First Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1910. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1910.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Thrirty-Second Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1911. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1911.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Thirty-Third Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1912. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1912.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Thirty-Fourth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1913. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1913.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Thirty-Fifth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1914. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1914.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Thirty-Sixth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1915. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1915.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Thirty-Seventh Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1916. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1916.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Thirty-Eighth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1917. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1917.

Ballenger, JH and Richards. Ballenger & Richard’s Thirty-Ninth Annual City Directory: Containing a Complete List of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Business Firms etc. in The City of Leadville for 1918. Leadville, CO: Ballenger and Richards Publishers. 1918.

To cite any of the information in this writing, please use the following reference.

AUTHOR: Robert-George de Stolfe

EDITOR: William Korn

SOURCE: Museum Exhibitions/Liquor Jugs

PUBLISHED BY: Temple Israel Foundation. Leadville, Colorado; USA. 2022.

STABLE URL: http://www.jewishleadville.org/exhibit-liquorjugs.html