Frontier Jewish Leadville is a permanent exhibition within the Temple Israel building. The original exhibition was formed with artifacts and informational wall panels in 2012 and 2013. It was expanded and retooled in 2014 and 2015 and partially expanded again in 2017. The original text on the wall panels, which accompanied the exhibition and were upgraded to wall-mounted monitors, is updated regularly as our research uncovers new information and interpretations.

All writing included in the links below has been revised.

Refer to the links below to view the permanent artifact exhibition.

Solomon Nunes Carvalho was Colorado’s first well-documented Jewish visitor. An accomplished artist and skilled daguerreotype photographer, Carvalho was chosen by explorer John Freemont to document his fifth expedition, which passed through what would become south-central Colorado in 1854. Born into a colonial-era Sephardic Jewish family based in South Carolina, Carvalho was also the first photographer to capture a scene in the region. His memoir of this trip, entitled Incidents of Travel and Adventure in the Far West; with Colonel Freemont’s Last Expedition, is the first compilation of a Jewish man’s travels in the territory and one of the first written accounts penned by a Euro-American Jew. Jewish life in Colorado clearly had promising beginnings.

Less than 10 years after Freemont’s expedition, the mountains of Colorado sprang to life. In the spring of 1860, gold was found in accessible pockets of the gullies and outwash channels of Colorado’s central mountains and Front Range foothills. A high gully above the Arkansas Valley originally called California Gulch suddenly burst with activity. Among the first settlers were two German-Jewish entrepreneurs named Simon Nathan and Wolfe Londoner (Denver’s first and currently only Jewish mayor, 1889-1891). Nathan’s second son, Lewis, was the first Jewish child born in the Colorado high country. Simon Nathan left Leadville in 1866 and was instrumental in establishing the first Reform synagogue in Pueblo, Colorado. Londoner became a successful businessman who set up an early mercantile shop in Oro City. Some fifteen years later, he returned to what would become Leadville. After the initial Colorado gold rush played out in 1861, the California Gulch fell silent for more than a decade.

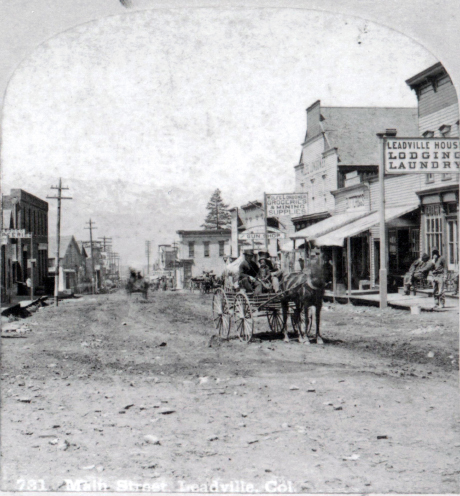

By 1876 and 1877, interest in the potential of silver-bearing carbonates ignited a new passion in the area. The beginnings of the city of Leadville started taking shape on the tableland north of the gulch. The stage was set for the most important decade of Leadville’s existence. The earliest seeds of Leadville’s Jewish community were sown in November of 1879. That month, Rocky Mountain Lodge no. 322 of the Independent Order of B’nai B’rith organized and held an inaugural banquet at Hotel Windsor. By that year, investment and growth were in full swing. Business and political leaders emerged from a merchant class of Jewish immigrants.

Migration patterns in Leadville mirrored those of many large U.S. cities during that era. As quickly as letters could travel, relatives, friends, and associates joined those early Leadville pioneers. Among those who built Leadville’s Jewish community were David May, Moses Shoenberg, Samuel and Elias Pelton, Mannie Hyman, Joseph and Marcus Monheimer, and Jacob Sands, among others. Chain migration played an important role in the foundation of this community. Many of these men married the sisters and daughters of their business associates. Children were born and a modern, cosmopolitan city developed on the edge of the Colorado wilderness.

From 1850 to the 1920s, the Jewish population in the western United States grew from a few to about 300,000 people. Jews migrated to the West and to Leadville for many of the same reasons other people did — to improve their social and economic status, for adventure, and a chance to reinvent themselves. Leadville’s mining economy exploded in the late 1870s, resulting in an influx of migrants to the small mountain town. The discovery of silver caused Leadville’s population to grow to approximately 30,000 residents. About 300 were Jews.

Many Jews immigrated to more hospitable places in the 19th century, when industrialized European countries became increasingly repressive. In Europe it was common for Jews find employment as seamstresses, tailors, and peddlers — work that was becoming obsolete in the new industrialized world. The United States, and the western U.S. in particular, provided ideal places to engage in traditional Jewish occupations. In the U.S., one could rise from an itinerant peddler to a merchant in a single generation. While the image of the Jewish merchant is now stereotypical, many Jews found that the role of merchant in the American West provided families with economic stability and opportunities for civic leadership. During the California Gold Rush of the 1850s, many Jewish merchants rose to social and economic prominence.

Patterns for establishing communal and financial stability can be found in many Old West towns of the 1800s. Typically, one family member was sent ahead to a small town to initiate a business outpost. Brothers, cousins and other male relatives would later join them to help run the establishment. It was not uncommon for these men to eventually marry the female relatives of their business partners. There are several examples of Leadville Jews utilizing this dynamic in community and commerce in this fashion, including department store mogul David May.

Leadville’s Jewish community was not entirely organized between 1879 and 1884. The B’nai B’rith charter shuttered due to dereliction of duty. Despite this, newspapers documented Jewish gatherings at various venues throughout the city, including a small meeting hall on Upper Chestnut Street. The Shoenberg Opera House served as Leadville’s first unofficial synagogue, and events for the Jewish community were hosted at both of Leadville’s Turnverein meeting halls. Prior to the construction of Temple Israel, an early Jewish wedding took place a St. George’s Episcopal Church. Various religious and ethnic cultures coexisted peacefully in Leadville.

By 1884, Jewish life in Leadville was healthy enough to afford a dedicated synagogue. This where the Temple Israel story begins.

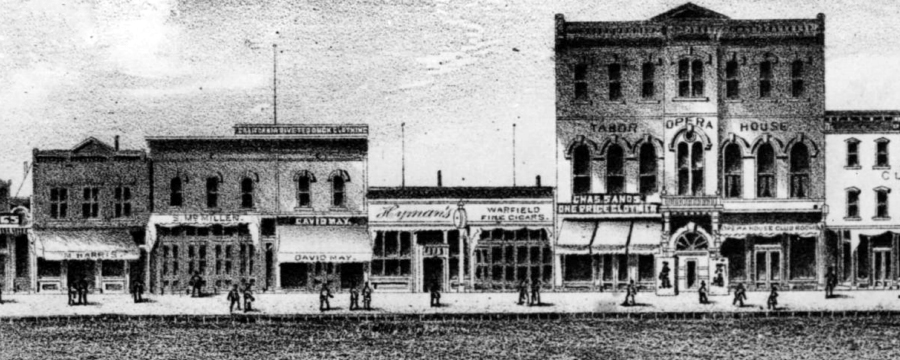

A drawing of the 300 block of Harrison Avenue in 1887 demonstrates the prosperity of Jewish owned businesses in Leadville. Among these enterprises are storefronts maintained by local Jewish business owners such as Meyer Harris (clothing), Mannie Hyman and Theodore Schultze (saloon), and Jake and Charles Sands (clothing). [6]

Jewish organizations began to appear in Leadville in 1879 and 1880. The Hebrew Ladies Relief Society may have been the earliest enterprise. Similar to other Jewish enclaves, these women were probably the driving force for organized Judaism in the Leadville community. They established annual fundraising events such as the Strawberry & Ice Cream Festival and the Purim Masque Balls, which were popular festivities in Leadville for decades. On June 3, 1879, the death of Jewish merchant Gustave Jelenko of Kokomo, a mining community located near the tailings ponds of the modern day Climax mine, generated an urgent need for a Hebrew cemetery.

In January of 1880, the Hebrew Relief Society successfully acquired 101,000 square feet of Leadville’s Evergreen Cemetery for Jewish burials. The remains of Gustave Jelenko were soon reinterred in Leadville’s Hebrew Cemetery. He was the first person buried there.

Leadville’s Hebrew Cemetery has withstood the tests of time and nature since its original consecration in 1880. The remains of 132 of Leadville’s early Jewish residents are interred here. As the population of Leadville declined, the condition of the cemetery did as well, enduring hardily through heavy mountain snows, forest overgrowth, and a minor act of vandalism in 1970.

The Temple Israel Foundation acquired ownership of the cemetery on June 18, 1993, through a quiet title suit. After years of clean-up efforts organized in conjunction with B’nai B’rith of Denver, the cemetery was fully restored, re-consecrated and used for modern burials in August of 1999.

Monheimer Brothers was one of the most successful dry goods and clothing shops in Leadville. Joseph H. Monheimer served as a county commissioner starting in 1883 and was elected president of Temple Israel Congregation in 1884. He later administered the estate of a well-known Leadville madam after her death.

Meyer Guggenheim was a novice investor with grand ideas. He came to Leadville in 1880 as a successful lace manufacturer with a small cache of accumulated wealth. He purchased the struggling A.Y. & Minnie mines and was able to finance the abatement of large quantities of groundwater, revealing a substantial vein of silver. His sons, Benjamin, Simon, and William, all spent time in Leadville monitoring the family’s business concerns over the ensuing years. By the 1890s, the Guggenheims had purchased the Arkansas Valley Smelter in Leadville in addition to other mining-related enterprises throughout the western hemisphere. These acquisitions made him one of the most powerful mining and mineral refinement operators in North and South America.

Some Jewish immigrants who dreamed of discovering silver discovered that fate had other plans. David May immigrated to the United States from the Rhineland at age 17, in 1865. He worked at a clothing factory in Ohio and also gained invaluable retail experience while employed at a clothing store in Indiana. In 1878, the call of riches in the California Gulch beckoned May to Leadville. He toiled that summer hauling ore up from the shaft with a windlass. Ultimately realizing that there would be no forthcoming financial reward from this arduous labor, May and his partners gave up on the claim.

May remained in Leadville and returned to his career as a clothing retailer. Initially pairing with his brother-in-law Moses Shoenberg, he opened The May Company on Harrison Avenue. The store grew into one of the largest clothing enterprises in the world. May, who served as Lake County treasurer, also became vice president of the Temple Israel Congregation. He was trustee of the land donated to the Jewish community by Horace Tabor in 1884 for the purpose of building Temple Israel.

Although gold originally attracted people to Leadville in 1860, it was the discovery of silver in the mid-1870s that caused the city to mushroom. By 1877, a massive influx of people sought to get rich quick through mining or mining-related enterprises. Similar to the 1850s California Gold Rush, most Leadville Jews ended up providing goods and services to miners.

While there are no known records documenting exact attendance numbers at Leadville’s synagogues, about 170 congregants attended Temple Israel’s dedication on Rosh Hashanah, September 19, 1884. Leadville Jews were active in both secular and Jewish organizations. Some were quite active in the Knights of Pythias, Elks, Masons, Oddfellows, and the Ancient Order of United Workmen.

Jewish Leadville organized several charitable organizations. Among the earliest was the Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Association (Society), which had roughly 40 members and provided financial assistance to local residents regardless of religious affiliation. The roster of names for women active in this group included prominent members of the Kahn, Schloss, Samuels, Miller and Schayer families. The benevolent association held annual charity functions that were also popular secular events in Leadville, including the annual Purim Masque Ball and the Strawberry & Ice Cream Festival. According to a report that appeared in the March 23, 1883, edition of the Leadville Daily Herald, Jews were not the only attendees at that year’s Purim festivities — “…a great many of whom were not Israelites.” Precise figures eluded the reporters because “it was a masquerade and the fun was great.”

Other organizations that made their impressions on Leadville’s social scene included a Hebrew school that was established in 1882 and hosted annual picnics. The B’nai B’rith Rocky Mountain Lodge no. 322 operated for about two years until it dissolved in 1881. The Hebrew Benevolent Association cared for Leadville’s sick and orphaned, provided aid and comfort to the needy and helped with burial expenses.

According to society gossip columns from late 19th-century local newspapers, Leadville Jews held numerous social gatherings that included elegant dinners, children’s birthday parties and Bar Mitzvahs. The Jewish community socialized together and with the population at large. Popular amusements in Leadville at this time included the traveling circus, a mind-reading event at the Tabor Opera House, concerts, gaming tournaments, banquets, sporting events and lectures presented by Oscar Wilde and other popular personalities.

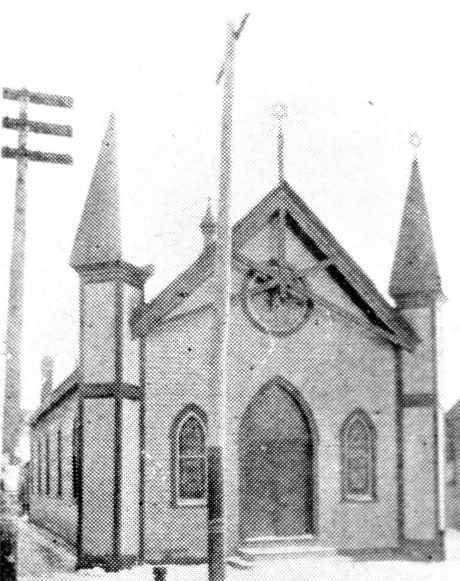

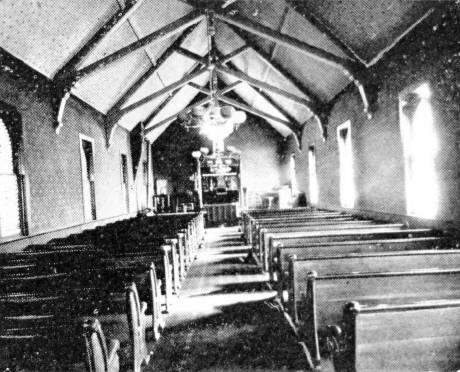

As early as 1879, Leadville’s Jewish population had grown sufficiently to warrant holding Rosh Hashanah services at the Shoenberg Opera House on Chestnut Street. Congregation Israel decided to build a synagogue on the land donated by H.A.W. Tabor, the “Silver Baron,” in August of that year. The new synagogue was constructed in 33 days for a sum of $4,000. On September 19, 1884, Rabbi Morris Sachs of Cincinnati, Ohio dedicated the building. The dedication coincided with Rosh Hashanah 5645, which elevated the congregation’s anticipation of a “Sweet New Year “in Leadville. The building would serve as Leadville’s sole synagogue for the next eight years.

By 1892, Reform and Orthodox Jews in Leadville found they no longer shared the same religious rules and split into two shuls. The Orthodox group purchased an old Presbyterian church on West 5th Street in late 1892, and began holding Orthodox services in 1893 at the newly formed Knesseth Israel synagogue (later demolished). Temple Israel continued offering Reform worship services and host cultural events such as concerts and balls. A lay leader served as cantor and led services at both shuls.

Only four rabbis conducted worship services at Temple Israel during its 46-year span. Rabbi Morris Sachs dedicated Temple Israel and orchestrated High Holiday services in 1884 but never returned to Leadville. Leadville native Rabbi Samuel Koch, a rabbinical student at Hebrew Union College in the late 1890s, conducted High Holy Day services in Leadville between 1896 and 1902. Rabbi Alfred T. Goldshaw led a weekend of lectures and services at Temple Israel in January of 2006. Rabbi Martin Mishli Weitz of the Association of American Hebrew Congregations also gave lectures and services while on a tour of Colorado cities in the autumn of 1930.

Dr. John Eisner of Denver, a traveling mohel, enabled Jewish families in Colorado’s mining towns to observe the tradition of brit milah (bris), or ritual circumcision, for male infants.

The Leadville community supported a Hebrew school for three decades. Kosher meat was available locally for one year, in 1880. Presently, there is no evidence that a mikvah (ritual purifying bath) existed in Leadville.

Since Temple Israel did not enjoy the presence of a permanent rabbi, Shabbat services are known to have been conducted regularly between 1884 and 1912 by lay-leaders. In addition to services, the shul’s Sunday school was regularly attended.

Temple Israel’s first cantor was Ben Davies, one of the most scandalous characters that conducted services at the synagogue. Davies served as the Reform cantor from 1883 until August of 1890, when he was dismissed after his affair with Mrs. Clementine Kahn Raabe became public. Clementine divorced her husband Julius Raabe and married Davies two weeks after his discharge. The Davies-Raabe saga did not end there. Clementine and Ben had two children, Lillian and Harry, before Ben died in a fire in his jewelry store on August 7, 1893. By late September, Clementine remarried Julius Raabe, who adopted Lillian and Harry and raised them as his own.

Prominent Leadville liquor merchant Adolph Schayer was installed as cantor in the wake of the Davies-Raabe scandal and served from 1890 until his death from heart failure in 1909. Marx Kahn served briefly as a relief cantor in 1901, while Schayer observed shiva (seven days of mourning) for his 15-year-old daughter’s death from appendicitis, on May 9. Schayer resumed his normal duties on September 13, when he conducted High Holiday services at Temple Israel.

Theodore Baer served as an assistant and a relief cantor from 1902 until his death in 1910. It is likely that no official services for the High Holy Days were conducted at Temple Israel after 1910; newspaper reports in the following years announced that Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services would be held at Knesseth Israel, noting that “...all other congregations in the city are invited to attend both services.”

Leadville was always home to Orthodox Jews, although their numbers rarely exceeded 40. The congregation went by many names until it officially adopted “Knesseth Israel” in 1892.

The divisive issues between Reform and Orthodox Jews in Leadville focused on gender integration, the incorporation of music during services and memorial rituals for the dead. The earliest documented evidence of a separate Orthodox congregation appeared in the Leadville Daily Evening Chronicle on October 9, 1886. The paper announced that Yom Kippur services were held by the Reform congregation at Temple Israel, while the Orthodox congregation met at City Hall.

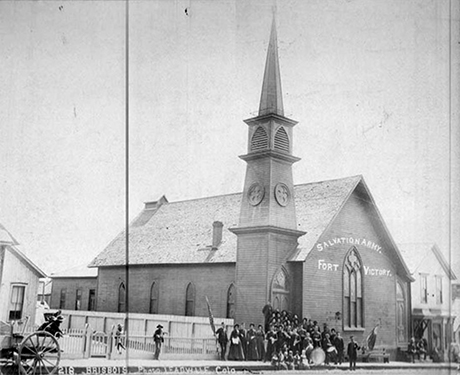

Knesseth Israel was on West 5th Street, shown here in 1892 shortly before they acquired the building. Brisbois photograph number 218.

September 25, 1888

The yet unnamed orthodox congregation, led by Zundel Greenwald, met separately from the reform congregation for Rosh Hashanah services at City Hall.

September 22, 1892The orthodox congregation, now known as Knesseth Israel, met for Rosh Hashanah services at Turner Hall.

November 3, 1892

The Knesseth Israel congregation purchased the old Presbyterian church located at 119 West 5th Street for $1,050.00.

April 11, 1895

An unattended candle caused a small fire in the synagogue and was quickly extinguished resulting in little damage.

1911-1937

Knesseth Israel fell into relative obscurity hosting only annual or bi-annual events.

September 3, 1928

While cleaning Knesseth Israel in preparation for High Holy Day services, Jake Sandusky discovers that the building had been burglarized. Among the items taken are draperies and the Torah cover, prized for the value of their velvet. It is soon realized that Sandusky’s housekeeper is responsible for the crime and all items were returned.

1937

The building was sold and demolished by its new owners.

Little information exists identifying which Jewish families were members of that shul. However, the longest tenured Jewish family in Leadville, the Millers, whose tenure began in 1892 and ended upon Minette Miller’s death in 1981, were Orthodox. Only a few rabbis sporadically served the congregation.

Rabbi A. Lavitzy gave the Kol Nidre (atonement) prayer and a Yom Kippur sermon at Knesseth Israel during High Holiday services on September 7, 1903, and Rabbi J. Greenwald of Denver led High Holy Day services on September 22, and October 1, 1911. Temple Israel cantor Adolph Schayer delivered religious rites for the wedding of Minnie Oliner to Aaron Walpensky at the Orthodox synagogue on April 1, 1900.

Zundel Greenwald began leading services for the Orthodox community in 1888, although the first mention of a cantor conducting services at Knesseth Israel does not appear in Leadville newspapers until 1897. Greenwald, a painting contractor by trade, served as the Orthodox cantor until his death on April 29, 1914.

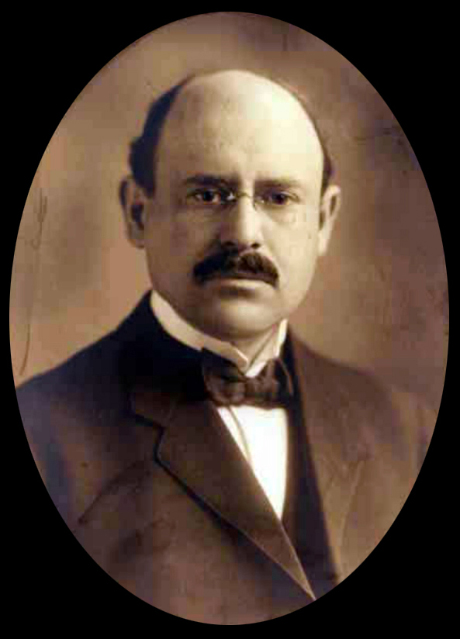

Nathan Miller immigrated to the United States from Vilnius, Lithuania in 1880. He moved to Leadville in 1892 after stints in Pottsville, Pennsylvania and Granite, Colorado. Miller is one of only a few Jews who came to Leadville with the intent to mine. The family dry goods store helped support his passion. Miller served as the Orthodox cantor from 1914 to 1918 and 1923 to 1934.

Mr. A. Unger was not a Leadville resident, but traveled regularly from his home in Salida, Colorado (roughly 58 miles away) for Shabbat services and holiday functions at Knesseth Israel. Unger occasionally led services but usually served as an assistant cantor to Maurice and Nathan Miller from 1918 to 1920.

Nathan Miller’s eldest son, Maurice, was the last known cantor for the Knesseth Israel congregation, serving from 1919 until leaving for Leadville for California in 1931. Maurice was a veteran of the United States Army during World War I. It is unclear whether he conducted services to relieve his father or alongside him.

Nathan Miller

In Leadville, similar to other mining towns, the miners worked arduously and played equally hard when the day was done. Options for entertainment and amusements in the 1880s were plentiful. A miner could spend his newfound bounty on liquor, women, or gaming at any one of 120 saloons, 150 gambling rooms, 35 brothels and two opera houses. Leadville Jews operated concerns in all of these categories. Hyman’s Club Rooms, one of these establishments, was owned and operated by Mannie Hyman.

Hyman’s saloon, notorious for its rowdy atmosphere and bar room brawls, lives on in western folklore as the scene of Doc Holliday’s last gunfight on August 19, 1884. Henry Kellerman, a Jewish deputy sheriff, disarmed Holliday and no one was killed. However, the incident significantly impacted Holliday’s already soiled reputation. After the trial, the gunslinger left town to nurse his deteriorating health in Glenwood Springs, where he died of tuberculosis on November 8, 1887.

Many of members of Leadville’s Jewish community belonged to secular social organizations such as the Masons, Elks, Oddfellows, Grand Army of the Republic, Knights of Labor, and the Turnverein Society. There were other social organizations and clubs created by members of Leadville’s Jewish community that required no religious affiliation and, at least for a time, were popular among Leadvillians:

The History Club first appeared in 1895.

The Jewish Ladies’ Reading Club was popular during the 1890s.

The Cloud City Social Club, a Jewish social organization, held dances featuring the Great Western Orchestra conducted by Professor Henry Simon. Prominent couples from Temple Israel attended the club’s first function on January 23, 1885, including the Hirsches, Baers, Kahns, Blumbergs and Simons. Also open to singles Carrie and Emma Kahn, Mannie Hyman, along with sisters Theresa, Hattie, and Jennie Schoenberg also participated. The club met on Friday nights every other week until 1890, when the club began to hold their parties every week. By 1894, the organization had grown to 40 regular members and moved their dances to every Saturday evening.

In 1895, the Cloud City Social Club switched to regular venue and attended Professor Martine’s weekly socials on Saturday nights at Armory Hall. The club’s mention in newspapers declined after 1895 because it was probably absorbed into the Friday Night Social Club, which started holding dances at the Armory Hall in 1900.

Judge Freauhoff delivered a lecture on the life of Sir Moses Montefiore on the 100th anniversary of his death on October 24, 1884, at Temple Israel.

Dr. William Friedman of Temple Emmanuel in Denver lectured at Temple Israel on December 14, 1889.

On January 21, 1907, a public debate on “Zionism,” a movement established in 1869 to foster a Jewish national identity and restoration of a Jewish homeland in Israel. Zionism was not a popular movement in Reform Judaism until after World War Two. Mr. H. Fishowitz of St. Louis argued for the pro-Zionist position while Temple Israel cantor Adolph Schayer presented the opposing viewpoint.

The two most common annual events among Leadville’s Jewish community were the Purim Masque Balls and the Strawberries & Ice Cream Festival. The Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society (Association) presented both events. The Purim festivities generally took place in March or April from 1879 until around 1900, and the Strawberry & Ice Cream Festival was held in June or early July, from 1883 until about 1898. Both secular events, there also were fundraisers for Temple Israel. In 1902, St. George’s Episcopal Church attempted to revive the Strawberries & Ice Cream Festival but there are no mentions of the event after 1905.

Purim Masque Balls were popular springtime events. This advertisement card promoting a New York Purim Ball in 1881 demonstrates the lavish costumes and decorations that were indicative of these celebrations commemorating the day that Esther, Queen of Persia, saved the Jewish people from annihilation by Haman, the advisor to the Persian king. [1]

Reinhold Rosendorf, a longtime Leadville barber and member of both Knesseth Israel and Temple Israel congregations, performed in community theater productions as an actor and a dancer. He directed the actors in a performance of Early Vows at the Tabor Opera House on December 11, 1882.

Musician Leo Klein performed at many functions for the congregation and the Leadville community at large. John Phillip Sousa recorded his composition The Sand Eaters’ March. Professor Henry Simon founded the Great Western Orchestra and together they performed at the weekly dances hosted by the Cloud City Social Club and at the annual Hard Times Ball. Simon also called the dances for the banquet in celebration of the establishment of Rocky Mountain Lodge No. 322 of B’nai B’rith in November of 1879.

After marrying Dr. Lee Kahn, author and poetess Ruth Ward Kahn made Leadville her home. A contributor to national periodicals such as the American Israelite and The Rocky Mountain News, Ruth also performed on the lecture circuits around the United States and the Caribbean.

Ben Loeb was one of the men who provided entertainment for the Leadville masses during the latter 19th century. The German-born pioneer arrived in Leadville via Texas in 1881 and quickly learned how to accommodate miners while managing the Delmonico Hotel & Bar on Harrison Avenue. This initiated Loeb’s rapid ascent from bartender to entertainment mogul. By 1890, Loeb owned three theaters in Leadville: The Carbonate; The Variety; and The Central Theater, renamed Loeb’s Palace of Pleasure, a burlesque theater and bordello, immediately after purchase.

Loeb’s establishments featured a “ladies’ entrance” and a telephone. Loeb, who also served the community as a promoter, organized a vaudeville performance at Leadville’s City Hall in 1889 that featured the legless singer and dancer James E. Black and Ranalzo the Human Corkscrew. His establishments often staged boxing and wrestling events. Loeb’s 1900 divorce from wife Georgia Flynn, which coincided with a financial decline, left him destitute at the time of death in 1912.

Loeb was not the only Leadville Jew active in this entertainment niche. Sam Lavinsky was the proprietor of a saloon called “Owl Joint,” located at 124 Harrison Avenue. The saloon and gaming house earned the reputation as nightspot rife with violence and boasted “lodging rooms which he rents without asking questions.” Once in 1895, Lavinsky raised Loeb’s ire after several ladies employed at the Palace of Pleasure and their clientele were discovered at Lavinsky’s saloon.

In April of 1887, Temple Israel President Joseph Monheimer was appointed executor of the estate of popular Leadville madam Molly May. He also served as the proprietor of her “House of Happiness” until it sold at auction later that September.

The Congregation Israel choir’s makeup was primarily secular; however, some musicians were congregation members. The following list records members’ names, their musical specialties and date of their first appearance with the choir:

Sam Rosenberg, organist (1886).

Morris Goldstein, vocal soloist (1886).

Cora (Leon) Simon, vocal soloist (1887).

Lottie Schloss, vocal soloist (1887).

Theodore Baer, vocalist (1895).

Minna Heimberger, organist (1895).

Jennie (Block) Hoffman, vocalist (1902).

Jesse Bloomfield, vocalist (1902).

Ethel Sandusky, vocal soloist (1902).

Myrtle Block, organist (1909).

Jake Sandusky, vocal soloist (1909).

Pearl Miller, vocal soloist (1909).

Julius Muller, clarinetist (1909).

Baseball became an extremely popular pastime in communities across the United States during the latter quarter of 19th century. Most large cities and small towns had some form of professional baseball, and Leadville was no exception. The Leadville Blues of the Western Baseball League was founded in 1882 with the help of their director, successful businessman and Temple Israel congregant Jake Sands. Sands paid top-dollar to attract some of the country’s best players. The team’s inaugural season, which boasted a 35-8 record, won all of its home games. Many baseball historians refer to the 1882 Leadville Blues as “Colorado’s best baseball team” of all time. The same historians added that the altitude at 10,200 feet left most visiting teams completely winded by the end of the second inning.

Following the Blue’s lead in wins during the 1882 season, the team took a road trip to Iowa. The Blues recorded their only losing streak of three games with a team stack ringers from the National League’s Chicago White Stockings (Cubs).

Owner Sands had an extra marital affair with the legendary Elizabeth “Baby” Doe in Central City/Blackhawk, Colorado, in 1878. Baby Doe moved to Leadville with Sands in 1880. She intended to marry him until she met his landlord, Horace Tabor. The Tabor-Doe liaison became a celebrated romance in Western literature, plays and lore. Jake Sands and Baby Doe Tabor maintained a close friendship until his death in 1916 at Bisbee, Arizona.

After an arsonist set fire to the Palace of Fashion and a large segment of Chestnut Street was later destroyed in an 1882 fire, Leadville’s volunteer fire department disbanded in favor of a professional force.

Isadore “Sam” Jacobs, a local Jewish tobacconist and firefighter, organized volunteers into Leadville’s competitive team of firemen.

Firemen’s competitions, which focused on how fast teams raced their horse-drawn fire wagons down Harrison Avenue and set up their equipment, became very popular.

Although Leadville’s professional fire force had a successful run, Jacobs did not fare well. Jacobs retired and moved to Denver in 1892. He was taking a test drive on one of Denver’s competitive fire wagons when the horse spooked and threw him into a utility pole. Jacobs, who refused medical treatment, passed away from his injuries a few hours later.

July 30, 1884

Land for Synagogue donated by Horace A. W. Tabor to David May, vice-president of the Congregation Israel.

September 19, 1884

The synagogue was dedicated on Rosh Hashanah, 5645.

1884-1910

The synagogue was in active, regular use.

November 1, 1912

The funeral service for Ausios Meyer Zeiler is the last official recorded event at Temple Israel.

1914-1937

The synagogue was still in limited use for special events and personal worship.

1937

Steve Malin purchased and converted the synagogue into a single-family residence. He lived with his family in the rear while running a radiator repair shop in the front.

World War II

The front portion of the building functions as a dormitory for local miners.

1955

St. George Episcopal Church across the street acquires the building and uses it as a vicarage.

1966

Ownership of the building changed again, and it was converted into a four-unit apartment complex.

1966 to 2006

The building continued in use as rental apartments.

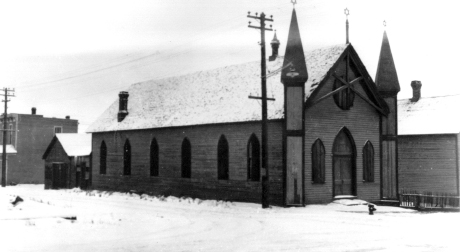

Photo of the exterior of Temple Israel in 1929.

1987

The Temple Israel Foundation incorporated “to acquire, historically rehabilitate, and maintain” the Temple Israel building and to research Leadville’s Jewish history.

October 15, 1992

The Foundation purchases the Temple Israel building.

June 18, 1993

The District Court awards the Foundation title to Leadville’s Hebrew Cemetery, rejoining parcels originally held by the Congregation Israel.

1993-present

Restoration and maintenance of the Hebrew Cemetery and the Temple Israel building remain under the Foundation’s purview.

2001

Thanks to contributions from private donors and the Colorado State Historical Fund (CSHF), the front façade is restored.

2006

An electrical fire damages the building, rendering it uninhabitable.

2007

Restoration begins with support of additional CSHF grants and private donations. The work crew examines original remaining painted plasterwork and refers to 1884 newspaper descriptions and an 1895 photograph to replicate the 1884 interior.

2008

Building restoration is complete.

2009

The Temple Israel building returned to its former look as a synagogue and can be used for special events.

2012-Present

The building opens as a museum with permanent exhibits documenting Leadville’s frontier Jewish history.

Photo of the exterior of Temple Israel in 1964.

The information in this booklet was compiled by the Temple Israel Foundation research staff who would like to acknowledge the following repositories and archives we most commonly used that provide us with historic documents, U.S. Census records, city directories, and indices that make our research program possible:

- The Colorado Historic Newspaper Collection

- History Colorado

- Lake County Public Library

- The National Archives and Records Administration

- The Hart Research Library

- Beck Archives at the University of Denver

In addition, the following secondary resources are frequently used in conducting our research:

- Blair, Edward. Leadville: Colorado’s Magic City. Boulder, CO: Pruett Pub. 1980.

- Breck, Allen DuPont. The Centennial History Of The Jews Of Colorado, 1859-1959. Denver, CO: Hirschfeld Press, 1961.

- Denver Public Library. Colorado Marriages 1858-1939. 2004. Denver, CO. USA. The Colorado Genealogical Society.

- Goodstein, Phil H. Exploring Jewish Colorado. Denver, CO: Rocky Mountain Jewish Historical Society, 1992.

- Griswold, Don L., and Griswold, Jean Harvey. History of Leadville And Lake County, Colorado: From Mountain Solitude To Metropolis. Vols. 1 & 2. Denver, CO: Colorado Historical Society, 1996.

- Manly, Nancy. Who’s Where In Leadville’s Evergreen Cemetery. Leadville, CO; USA. Historical Research Co-operative. 1981.

All images used for this booklet are the property of the Temple Israel Collection except for the following:

- David M. Lesser, Fine Antiquarian Books LLC. Woodbridge, Connecticut. https://www.lesserbooks.com.

- Kahn, Ruth Ward. The First Quarter. Cincinnati, O.H: The Editor Publishing Co. 1898. Page 2.

- Roberts, Gary L. The Leadville Years. True West Magazine. November 1, 2001.

- Theresa Grossmayer. 02336CC. Leadville, CO: Colorado Mountain History Collection: Lake County Public Library. 2017.

- Manning, Jay F. Leadville, Lake County, and the Gold Belt. Denver, CO: Manning, O’Keefe, & DeLashmutt. 1894. Page 106.

- Leadville Herald Democrat, Jan. 1, 1887. Denver, CO: Western History Collection, Denver Public Library, Denver, Colorado. 2018.

- Koch, Samuel 1906-1920. PH COLL 650, JEW0499. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Special Collections. Jewish Archives Collection. 2019.

- Henning, Holly. Armory Hall-Leadville. 00637PL. Leadville, CO: Colorado Mountain History Collection: Lake County Public Library. 2016.

Special thanks to the Denver Public Library, The Hart Research Library at History Colorado and the Colorado Mountain History Collection at the Lake County Public Library for their patience and research assistance. The Temple Israel Foundation is grateful to its donors who help make the exhibition and preservation of Leadville’s Jewish history possible and most particularly to the anonymous donors without whose support this entire enterprise would not have been possible.

Writing was revised in August of 2019